Ella McCay: A Swing and a Miss

It’s been a year of philosophically incoherent movies, and James L. Brooks is here to deliver one last misfire for the 2025 canon. Ella McCay, which comes 15 years after his last production, has none of Brooks’ trademark mix of comedy and sentiment honed in movies like Terms of Endearment and Broadcast News. Instead, we’re treated to a bizarre motley of characters who enter each scene as though they’ve never met each other before, combined with a storyline on a strong, independent woman in politics that might have felt fresh 40 years prior but lands with an out-of-touch thud in the 2020s.

The movie is set in the apparently halcyon days of 2008—“back when everyone liked each other,” our narrator and Ella’s secretary (Julie Kavner, the voice of Marge Simpson), tells us unconvincingly—in an unnamed state, where the eponymous Ella (Emma Mackey) is a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed lieutenant governor. She has an innate sense of justice and political idealism honed from a young age, as revealed in sporadic flashbacks. We see young Ella confront her father Eddie (Woody Harrelson) about his repeated affairs, refusing to accept his blustering excuses while trying to protect her younger brother Casey and have a backbone on behalf of her mother (Rebecca Hall, criminally underused here).

20-odd years later, Ella’s kept that conscientiousness alive and well despite her chosen profession and the myriad of troubles facing her. There’s the fact that her mentor Governor Bill Moore (Albert Brooks) is planning to step down after accepting a position in the new presidential administration, leaving Ella to take on his role and overcome her lack of popularity with her fellow policymakers. Noticeably, Obama is never mentioned by name and Ella and Governor Moore are not given a stated party affiliation, creating an odd air of political unspecificity. Her ascension to governorship is threatened by a reporter who’s set to break the story of her lunch-break trysts in a government building with her husband Ryan (Jack Lowden)—an attempt at preserving their marriage that in fact breaks several laws. And beyond the professional, there’s the personal troubles like Casey (Spike Fearn) ignoring her calls and Eddie, estranged for over 10 years, popping back up to beg his children for forgiveness.

If that sounds like a lot of plot points to balance, it’s true, and it is a credit to Brooks that he manages to give equal weight to Ella’s professional and personal concerns. Mackey also succeeds in endearing Ella to the audience. She delivers Ella’s lengthy political speeches with a sincerity conveying her belief in politics as a tool to do good in the world, even as her colleagues scoff (or fall asleep, in a repeated gag). And as Ella finds it increasingly harder to bottle up her real feelings and put on a happy face for the public and for her family, Mackey believably portrays her character’s see-sawing emotions.

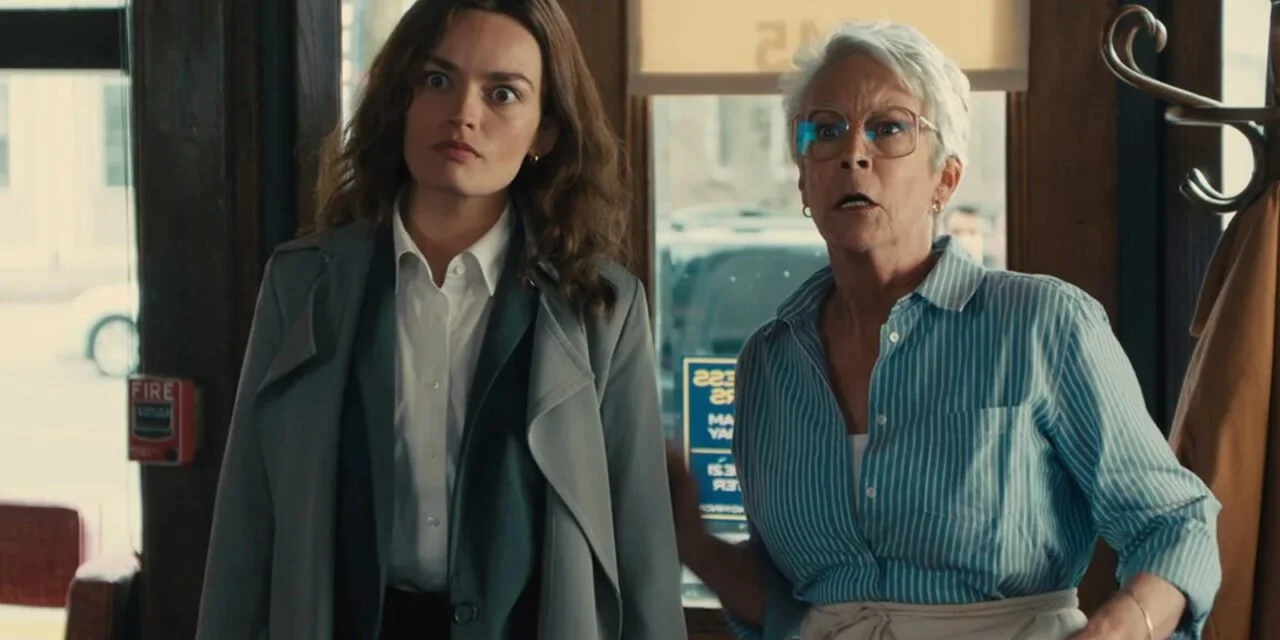

Beyond Ella, though, the movie is overstuffed with characters intended to be lovable oddballs but coming off as aliens with obscure intentions. Jamie Lee Curtis plays Ella’s Aunt Helen, a defining figure in her life, with an almost absurd screwball-esque energy that makes it seem as though she’s in a completely different movie than Mackey. Brooks might have aimed to position her loud and boisterous personality as a foil to Ella’s buttoned-up character, but strange comedic timing from Curtis and unfunny jokes make it seem more like Aunt Helen is socially inept and unanchored to the film. Ella’s strained relationships with her father and her brother Casey are compelling, but Brooks undermines the latter with an overlong subplot about Casey’s agoraphobia and attempt to win back an ex-girlfriend (Ayo Edebiri, disappointingly one-note). Then there’s Ella’s husband Ryan, portrayed as such a buffoon that one wonders why and how Ella, otherwise a pragmatic and self-confident woman, has stayed with him since they were high-school sweethearts. (Brooks has both Mackey and Lowden portray their younger selves in flashbacks, a baffling choice a la Ben Platt in Dear Evan Hansen.) And in a transparent attempt at showing how beloved Ella is by those working for her, Brooks throws in Kumail Ali Nanijiani as her bodyguard and chauffeur, whose one painfully unfunny bit centers on Ella being unable to hear him when he talks to her while driving.

Beyond the comedic and character misfires, there’s a real problem with Brooks’s inability to say anything of meaning about politics in a movie that is, ostensibly, about politics. Ella’s refusal to play the game as politics is her defining feature—and while she might be an earnest champion of policies that will help her community, it’s hard to believe she even ended up in the second-highest state government role given her track record of political unpopularity. And while politics in the mid-2000s certainly weren’t as overtly hostile as they are now, Brooks politically neuters the movie to the point of inanity in his attempt to show that a pure heart can win—or, as an overbearing narration from Marge Simpson states at the conclusion of the movie, that “the opposite of trauma is hope.”

If you enjoyed this article, please consider becoming a patron of Hyperreal Film Journal for as low as $3 a month!

Alix is the editor-in-chief for Hyperreal Film Journal. You can find her on Letterboxd at @alixfth and on IG at @alixfm.