The Shop on Main Street: How to be a Good Person in Difficult Times

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the 1965 Czechoslovak film The Shop on Main Street Lately, probably for no particular reason. Released only 20 years after the end of WWII, it is more interesting to me at this moment than a number of action war films about the fascist era. It is a film about the tragic and the mundane realities of living under fascism and moral choices that everyday people are confronted with. First, a little historical background. The film is set in a fictionalized small town in Slovakia during the short lived Slovak Republic(1939-1945), a clerical fascist puppet state created in the aftermath of Nazi Germany’s annexation of the Czech part of Czechoslovakia in 1939. Its motto was Faith, Family, Fatherland, apropos of nothing in contemporary society, surely.

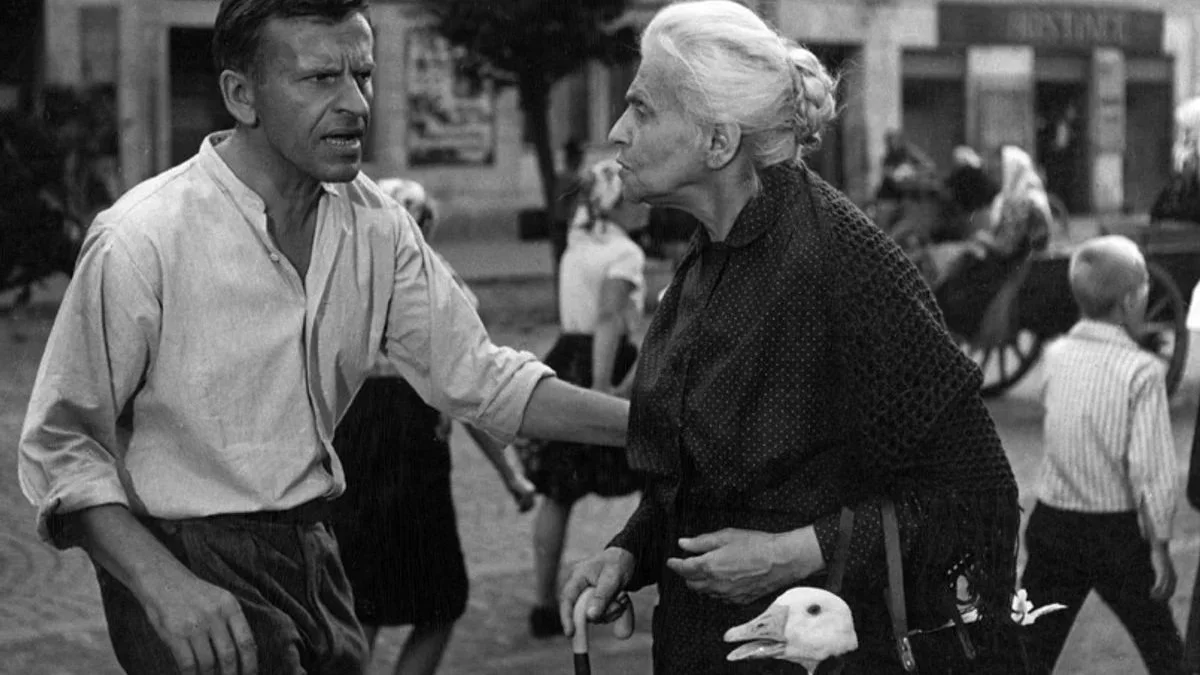

The plot revolves around a local member of the town's working-class, Tono Brtko (Jozef Kroner), a carpenter. Tono is a poor but hardworking man, struggling to get by and provide for his unsatisfied wife, who yearns for the finer things in life. Luckily his wife’s brother is a mid-level official in the Slovak fascist party, in charge of the “Arynization” (or would it maybe be ‘Slovakization?’) policy in the town. Through this local connection and his wife’s hectoring, Tono agrees to be placed in charge as the “Aryan steward” of a local tailors shop run by an elderly Jewish widow named Ida (Ida Kaminski). However, Ida is so elderly that her hearing is mostly gone and she doesn’t understand the purpose of Tono’s visit when he appears. She believes he is here to help. And on top of that, it turns out the business is underwater. The local Jewish community had been quietly funneling money to Ida’s shop for years in order to keep it afloat. A representative of that community comes to Tono and offers to pay him some of that money so Tono is not replaced with an actual committed fascist and antisemite. Tono agrees and is recruited into Ida’s workforce. There are some comedic bits here as he often ineptly tries to help her run the shop, while still fronting to his brother-in-law that he is merely preparing to take over completely from the old woman.

And that’s the thing about Tono; he isn’t anti-Semitic, and doesn’t like the fascists. His face is a mask of disgust every time he passes them in the street and is clearly upset at the authoritarian turn society has taken. He clearly intensely dislikes his brother-in-law, large part because of his role in the regime. Yet, this movie is an excellent portrayal of the ways in which decent people, out of nothing more than apathy and cowardice, and simply wanting to keep their head down and get by, can be enablers of much worse. When fascist governments come for racial or religious minorities, they rely on the mass of the population to act like Tono, even if they don’t like it, quietly acquiescing as their neighbors are hauled away, confident that they will not risk themselves to defy them. This is what makes the situation so difficult for an average person like Tono, or for any average person that might be watching the movie and living through similar times.

The lighting highlights this tension. The stark black and white give the movie a menacing glare. It serves to highlight the moral stakes. There's a sickening inevitability to the whole thing. Directors Jan Kadar and Elmar Kos, working with a lean 125 minute runtime and a tight script by Ladislav Grosman, allow scenes to breathe, with long steady takes. It’s an economical movie with not one scene wasted. Kroner and Kaminski give excellent performances. Kroner plays a rough yet compassionate everyman well, while Kaminski is a gem. Her Ida is a flurry of joy and energy in an otherwise stark movie. It’s no wonder she was nominated for Best Supporting Actress at the 1965 Oscars.

As the repression increases, it comes to a tragic and humanistic ending. It is one of the more gut-wrenching and heartbreaking endingsI’ve seen recently. It reinforces the theme of the moral choices people are forced to confront in these types of historical moments. This classic absolutely deserved its win for Best Foreign Language film at the 1965 Academy Awards. As for today, it is a tragedy beyond words that, due to recent political developments, you can feel this particular moment in history resonating so loudly. To paraphrase a quote I’ve seen floating around recently, “if you ever wondered what you would do during a fascist takeover, you’re doing it” Unfortunately, I can’t recommend it enough.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider becoming a patron of Hyperreal Film Journal for as low as $3 a month!

Andrew Turner is a writer based in Austin, TX. He draws his insights on film from his background in History and Political Science and is interested in how these intersect with each other. He has lately been writing about 20th century history and film, particularly of the Eastern bloc. He also has an interest in his own native central Texas, its politics, food, economy, and cultural output. He recently wrote about the rise of Austin to its current status as a major technopolis. He has written for the Austin Chronicle, The Quorum Report, and also can be found on substack.

https://andrewturner.substack.com/