The Glassworker spins a striking tale that gets why Miyazaki’s work is so beloved

Of all the insidious things about the recent plague of AI slop that tries to mimic the work of Studio Ghibli (specifically director Hayao Miyazaki), the flattening sticks with me. To the algorithm and the schmucks who turn to it for dopamine, Ghibli and Miyazaki are pastoral vistas and wholesome young people and piles upon piles of anime food and nothing else. There’s nary a look at the way violence corrodes all it touches, nor a struggle with life’s impeccable ability to hurt to be seen. Maybe there will be airships, but probably not pigs. In other words, it lacks the concerns, idiosyncrasies, and passions that make Miyazaki and company’s work recognizably theirs. It’s a substance-free lie. It’s the photo negative of Pakistani director Usman Riaz’s gorgeous animated feature The Glassworker, which played Austin’s 2025 Indie Meme Festival in April. While The Glassworker doesn’t quite stick its landing, it’s a very good movie on its own and as an homage to Miyazaki and his peers. It’s thoughtful, thorny, and willing to ride ambiguities and uncertainties.

Vincent Oliver (Sacha Dhawan in English and Mooroo in Urdu, Teresa Gallagher and Mahum Mozzam as a child—the English dub was watched for this review) is a master glassworker. As he prepares for his first major exhibition, he reflects on his youth. He learned glassworking from his father, Tomas (Art Malik and Khaled Anam), a glassworker in their beautiful, prosperous seaside town. The Olivers’ work was well-regarded, Tomas’ committed pacifism less so—their home sat on the edge of a bitterly contested border, where tensions over a valley rich in precious mineral resources regularly threatened to boil over into war. As those tensions spiked and then spiked again, the military deployed a garrison to the town, commanded by the dashing Colonel Amano (Tony Jayawardena and Ameed Riaz).

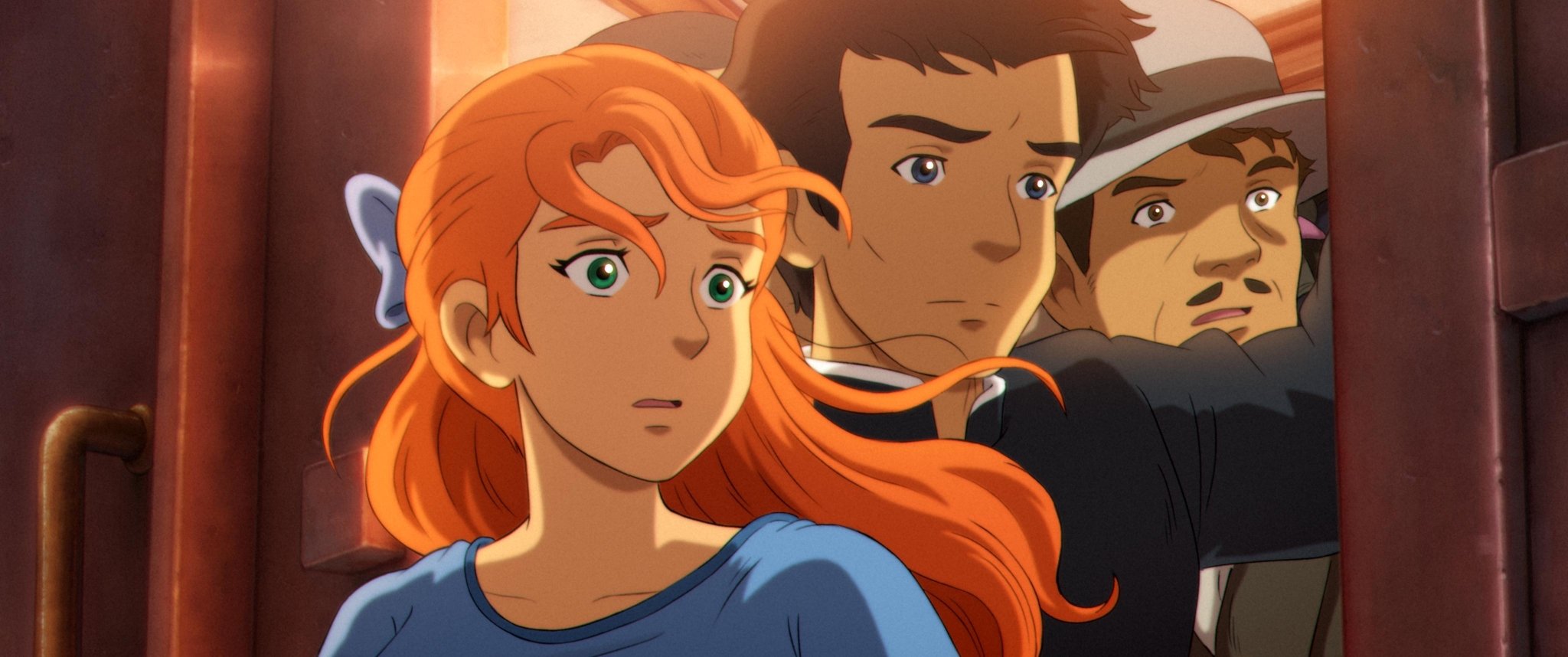

Amano moved his family with him, including his bright, musically inclined daughter Aliz (Anjli Mohindra and Mariam Riaz Paracha), who studied violin at the town’s esteemed conservatory. Despite their vast differences in social class and their fathers’ vast differences in ideology, Vincent and Aliz became friends, and as they grew, best friends whose platonic love might turn romantic. And the war came. It brought ruin, feeding young men like Aliz’s conservatory classmates into a woodchipper. It brought compromise, as when Tomas agreed to manufacture precision instruments for the nation’s aeronavy so that Vincent wouldn’t be left alone and could complete his glassworking education.

Most of all, the war brought transformation. Vincent and Aliz’s relationship was sorely tested by their drastically differing perceptions of the war. Vincent’s bully Malik (Sham Ali and Dino Ali), who’d long loved the idea of Aliz, screwed up his courage to the sticking place and acted heroically amidst battlefield catastrophe. Aliz questioned her moral responsibilities as the daughter of a high-ranking soldier. Vincent faced the bitter reality of holding to his pacifist convictions amidst jingoism and despair.

The Glassworker’s coming of age thrives when it embraces the awkward and uncomfortable. It creates space for its cast to be dimensional, to grow and change, and push against themselves. Vincent’s pacifism and Aliz’s love for her father are admirable. Vincent’s got an ego. Aliz has tunnel vision. They’re also awkward teenagers figuring themselves out in the middle of a war they’re both directly caught up in, which means they can be awful: catty and cutting in painfully specific ways thanks to their long friendship and burgeoning romance. Growth and learning come with hurt, but at their cores, Aliz and Vincent are good kids who want to do and be good—they’re compelling, sympathetic leads. Mohindra and Dhawan voice them well during The Glassworker’s dramatic and gentle moments.

Riaz, screenwriter Moya O’Shea (who wrote The Glassworker’s story together), and their team build a striking world that’s granularly specific at the personal level and broadly, if effectively sketched at the national level. It’s more important to the film that the Olivers are treated shabbily by their neighbors for their pacifism than the histories of the nations in the conflict and the histories of their conflicts. The picture revels in following Vincent and Aliz as they ply their creative trades, growing in skill as a glassworker and a musician. Vincent’s work to craft a hairclip for Aliz is one of the picture’s highlights, as he moves from conceptual sketches to finalized blueprints to the logistics of getting the right materials to the crafting itself. It’s wonderfully animated and a passionate, transfixing piece of filmcraft in a movie made with skill and care.

It’s frustrating that The Glassworker fumbles its ending after a film that thrives in discomfort and ambiguity, in specificity and passion, and on the push-and-pull of Vincent and Aliz’s care for each other. Some of this is down to the film’s mostly low-key supernatural subplot suddenly skyrocketing in importance and overtness so abruptly that it becomes jarring. Most of it is down to Aliz’s flattening from compelling, dimensional co-lead into magical, voiceless reward. Acknowledging that the specifics of what’s going on in The Glassworker’s ending are ambiguous by design, it’s a strange, sour note that does a disservice to its heroine.

Until the ending, though, The Glassworker is a fine film and a shining example of how to take love for a fellow creative’s style and work and spin it into a work as distinct and vibrant as its inspiration. It’s not a home run, but it swings the bat with care, skill, and style. With its stumbles in mind, it’s well worth a watch.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider becoming a patron of Hyperreal Film Journal for as low as $3 a month!

Justin Harrison is an essayist and critic based in Austin, Texas. He moved there for school and aims to stay for as long as he can afford it. Depending on the day you ask him, his favorite film is either Army of Shadows, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, The Brothers Bloom, Green Room, or something else entirely. He’s a sucker for crime stories. His work, which includes film criticism, comics criticism, and some recent work on video games, can be found HERE.