Love & Pop: The Crisis of Digital Video

You’d be forgiven for assuming that the works of Hideaki Anno are “boy stuff.” Specifically, cartoons for boys. The magnum opus of Le Maitre is the constellation of anime known as Neon Genesis Evangelion. Centered around Shinji Ikari’s adolescent male psychosexual despair, Evangelion is replete with masculine self-hatred transmuted into lashings out against the women in Shinji’s vicinity. Even Anno’s die-hard fans gravitate towards his minor animated works (Nadia of Blue Water or Kare Kano) when looking for an additional fix of his genre-deconstructing genius. Thanks to anime distributor GKIDS, however, Anno’s live-action masterpiece, Love & Pop (1998), finally made it to the North American big screen this year (including at Dallas’ own Texas Theatre). The 27-year old film follows Hiromi Yoshii and her crew of high school girlfriends as they navigate adolescent female psychosexual despair during Japan’s Lost Years of economic stagnation. It’s an unexpectedly mundane setting and story from Anno to follow Evangelion’s postmodern cosmic mecha mania. It’s precise in taking a microscope to modern girlhood in an all-too-ordinary setting, however, that Anno’s visionary commentary identifies existential threats to our shared social fabric in the rise of digital video, particularly: the normalization of sexual violence, the attenuation of our attention, and the collision of our private and public lives.

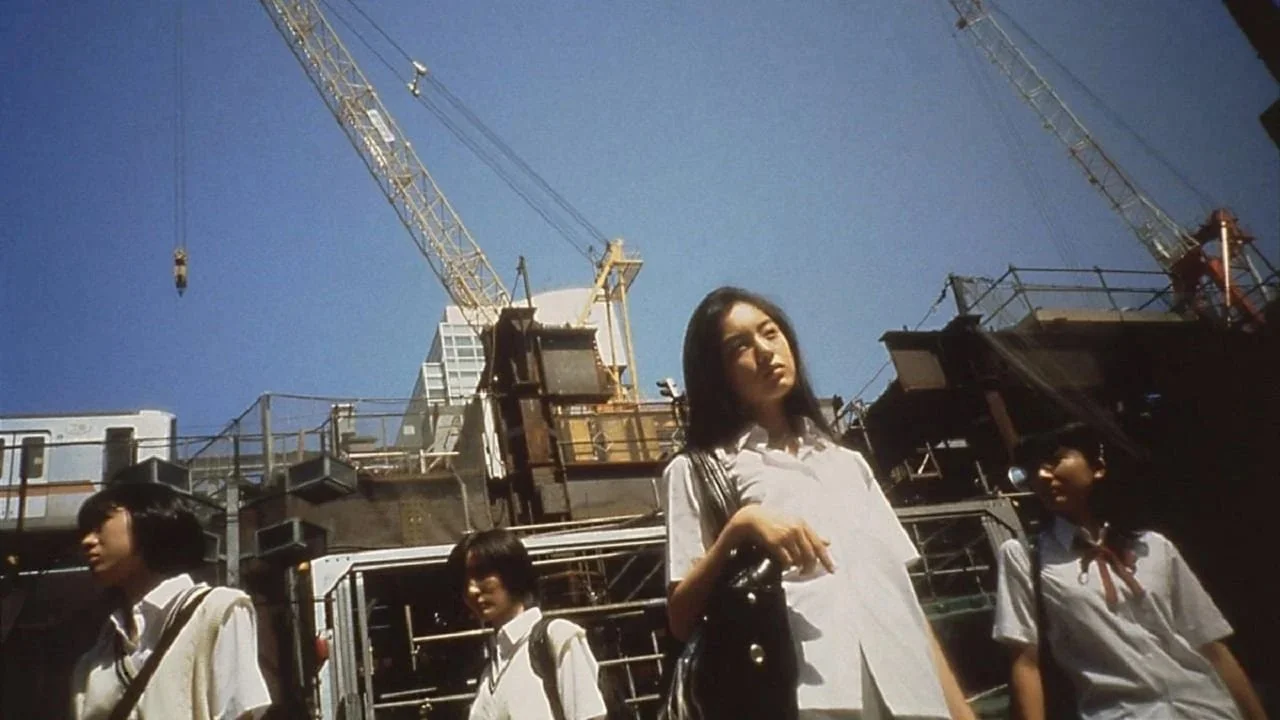

And ordinary it is. We are introduced to Hiromi through digital camera footage that could easily have been pulled from a touching home video. The teenage girl wakes up lazily and emerges to a bustling house—father playing with model trains, older sister reading with an aloof attitude, and mother moving about to get everyone fed and ready for the day. Mother and younger daughter trade goofy looks. It’s a lazy day in a comfortable middle class apartment. We can’t see what’s going on outside this small corner of Tokyo. Hiromi’s friends — Nao, Chieko, and Chisa — are your regular teenagers looking for ways to laugh together. They go on dates with boys, have dreams for the future, go to school, wallow in existential dread, go out to dinner, and make funny faces when a camera is pointed in their direction. Schoolgirl uniforms and red bikes, days spent languishing in summer boredom. Languishing because the adolescent can feel, in their body and their mind and their relationships with the world, that the times they are a-changing. “All I know is worldly things always end. Feelings, too… Maybe the world is just the same stuff, over and over,” Hiromi laments in a monotone monologue. Childhood passes, the future opens precariously. Soon, high school life will pass and all this will be a memory. In resisting her ennui, Hiromi becomes a filmmaker: “That doesn’t mean I can’t try and catch it before it goes.” She loads her digital camera with a fresh cartridge.

This nostalgic, familiar home video texture and the languor of Hiromi’s ennui are jolted from their comfortable rhythm by Anno’s aggressive, choppy edits. As we see the girls experience a unique form of joy and collective identity through their creating of digital photos and videos, the viewer is oriented towards the nefarious underbelly of the multiplication of cameras in the digital age. Yes, the girls now capture elements of their mundane life (father's home train models, older sister reading a book and acting annoyed, a day in the life at school). And yet: the private world we inhabit becomes, increasingly, available to the roving eye of the digital camera. We inhabit the following points-of-view: the microwave, the walls, the floor. (What might Anno say about Meta’s attempt to revive smart glasses?) When the teenage girls eat, the camera sits right in front of their face, turning us into voyeurs staring into their mouths for the price of a ticket. Most insidiously, the shots of the girls legs under tables, up their skirts as they ride bikes, intrusions into the bedroom, trains passing between their open legs. The era of home video is the era of omnipresent surveillance. In other settings, the question of surveillance might ask our analysis to unpack the following terms: national security, counterterrorism, civil liberties, political repression, privacy. Anno instead interprets the question of surveillance as one of sexual violence, the conflict of private worlds being simultaneously penetrated by the camera and multiplied through the proliferation of digital video copies. Citizens surveil other citizens. In particular, men ogle, stare, and obsess over teenage girls (cue one of American English’s slimiest phrases: “barely legal”). In Japan, one finds the problematic institution of enjo kōsai. Translations of the phrase are contested. In general, however, this practice is distinct from traditional prostitution. This modern “subculture” can be understood as older men paying younger (indeed, underage) women and girls to spend time with them. This may constitute sexual favors (ie. child prostitution) or spending an evening together singing karaoke. Which is to say: Anno implicates the audience via our spectatorship in this voyeurism. What he attempts, precariously, is to attend to the messy emotional reality that leads to enjo kōsai from the girls’ perspective, by neither aggrandizing the actions of the girls nor blinking when faced with the horrors of the situation, towards a holistic understanding of the networks of power and existential desire at play.

The girls take the train to Shibuya. Crossing the tracks, the girls are immediately met with a slew (a barrage, even) of men in business suits sexually harassing them. Anno raises the question: If the girls are going to be harassed (openly, loudly, and violently in broad daylight) anyways, why not make it profitable? The first several sessions with various men are, shockingly, tame. The girls are treated to large, expensive meals as classical music plays in the background. The men ramble on. Violence looms when the men yell or the camera jerks as they gesticulate. And still, the girls reclaim agency in this male-dominated sexual-political world and get away with a fair share of money. They continue, by all metrics, being teenagers (slumber parties, talking about boyfriends, going to karaoke). Throughout the laughter and the games, Hiromi’s ennui continues with a deep sense of emptiness and longing to break out of her mundane existence. He allows us to see the appeal to the girls of getting to step outside of their lives (under the shadow of Japan's economic crisis of the '90s) through tame, nonsexual interactions with older men – to have, well, money for themselves.

During a visit to the mall, Hiromi has a mystical experience. Seeing her reflection in a topaz ring, she is mesmerized. When the girls don’t have enough money to buy the ring, they take up a man’s offer to sing karaoke with him for a whopping 120,000 yen. He promises not to ask for anything sexual. Each girl pitches in their effort to make Hiromi’s dream come true. What’s so terrible about that? Flashes of home video intersperse the performance of love songs new and old.

And then… the man asks them to each chew a grape.

He unveils a kit built to carefully record and store half-chewed fruits from, apparently, dozens of young women. “If you create it, it’s still a part of you,” the man says. In recording the girls through the physical medium of the grapes, he claims ownership over them in a way not bound by temporal laws or money. He has degraded them and himself (in his shameful, duplicitous request) and thereby created a chimeric construction. What had been a deal for nonsexual companionship has entered a gray zone. Indeed, the surgical and methodical nature of the man’s data collection is itself dehumanizing, even if it doesn’t cause direct physical harm to the girls.

And perhaps all this was for naught. The girls are scrunched into a tight vertical frame as Hiromi cries and rejects the money. It must be split evenly between all four. The price was too high. Thus, Hiromi must hit the streets to make up the remaining amount for her ring. Using a cell phone, Hiromi locates men asking for non-sexual favors (with her friends giving advice before taking off). Uehara is an incel (an anachronistic term, he represents an early model of this digital subculture), a shut-in too afraid of women to speak with them. Emasculated by his practice of renting adult videos in person, he wants Hiromi present at the rental video store to prove to the store owner that he isn’t a “loser.” Once again, this straightforward assignment (taken out of desperation for money) quickly derails. Hiromi is made nauseous by the sheer volume and violence of pornography videos in the rental store — no longer classy Playboy magazines of adult models lounging about in makeup under nice lighting. Each title (referring to: incest, BDSM, kinks, and so on; one title goes “Rape and Rape and Rape”) is the story of another girl (very likely underage) caught in a moment of precarity and brought along to play for the camera so that men might make them into a fantasy. While Hiromi is stunned, Uehara forcibly has her masturbate him in the back aisle.

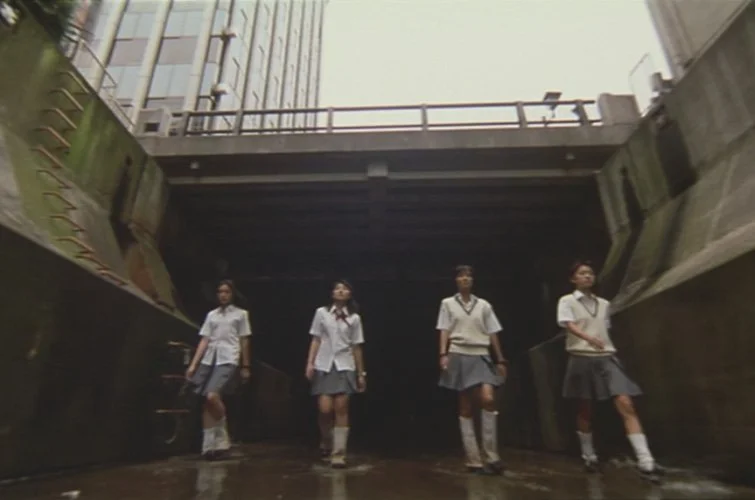

Running away, Hiromi is still short. She chats with the pimp on the phone. He complains about his love life, his boyfriend having dumped him through a message to Hiromi. Isolated and talking to a strange man through the phone, Hiromi accepts one last job that will pay for the ring. Whereas earlier, Hiromi had voiced a desire to move towards healthy intimacy (“More than having sex, I just want to quietly cuddle together”), her experiences have numbed her to the violence. The affable bucket-hat-wearing John, Captain EO, carries around a Fuzzball stuffed animal in need of repair. Going to a love hotel, Hiromi “saves” the animal by stitching it. As she takes a shower before the main act, Captain EO bursts into the bathroom wielding a stun gun. Hiromi (and the audience, no less) is jolted out of her complacency. We know that she could easily have died. The assailant leaves her alive and berates her for joining him (sharing a plan to kill her and take her money). “Maybe that someone’s heart is breaking,” he says, referring to someone, anyone, in Hiromi’s life who would miss her and who might be shocked to see “the girl so important to them was naked before a strange man.” Having failed to acquire the ring, Hiromi meets the pimp to return the phone. Despite his buttoned-up appearance and demure attitude, he radiates a menacing aura. Hiromi repeats the words of the assailant to the pimp. “It means a kind person, whoever said it. It’s a way of saying, ‘You have value.’” Hiromi returns home, greets her parents, and collapses in her bedroom. Taking the (ruined) film out of her camera, she lets it fall to the ground. She abdicates her role as filmmaker.

Whereas Neon Genesis Evangelion’s chronicle of (queer) adolescent male psychosexual frustration identified the masculine struggle to enter adulthood in arrested development and the idealized objectification of women (see: the manosphere), Anno sees modern adolescent female sexual dysfunction in an apathetic hypersexuality. Older men chase the girls, leer at them, make crude remarks on the street. When the girls step into taking calls, they are attempting to reclaim a sense of agency in this world beset by darkness. And yet, they enter deeper into a circle of danger. (For further reading, see The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and A Tale for the Time Being.) Anno depicts the girls starting this “harmless” task with caution before slowly being confronted with flashes of violence. The narrative reaches an abyss in Hiromi's near murder and rape by her last customer. Despite East Asian love hotels having commodified and regulated sex work along lines advocated for by sex positive Western critics, Hiromi would still have been murdered. Paying for sex in a safe, regulated space (complete with cameras and alarms) is no good when the structure of desire that surrounds this production preys upon vulnerable young women, acclimatizes them to sexual violence, and then proliferates itself through violent videos at high velocity. The dangers are spiritual and physical. The pay is minimal. Anno is visionary in his prognosis of digital video’s trajectory. The relationship between men and women (and boys and girls) is mediated through digital video and digital audio: it is simultaneously an expansion and distortion. Each side retreats into their own corners: The men no longer see women or girls as humans, consuming images of them in vast quantities divorced from their humanity or personality. The women see in men more and more an animalistic, sadistic tendency. The girls are shoved into vertical frames (side-by-side) in Subway Surfer brain-rot video format. Anno challenges us to attempt to read the triptychs and overlays, the screen is overwhelmed by its own hyperproductivity. In our current moment of TikTok slop, the mass proliferation of pornography to minors, and increasingly violent misogynistic manosphere spaces online, it’s clear Anno knew the dangers of digital video before the rest of us. Not to mention the evolution of loner male psychological disorder from the incel to the gooner and the increased danger to children posed by online predators. What began as a cheap and easy way to make videos has landed us in a no-man’s land of despair.

For a frenetic, postmodern Japanese film portraying economic malaise and sexual violence, the film has a surprising soundtrack. This story finds Western classical music entering Japanese homes en masse through radio and CDs during the 1980s-1990s. What would have been a performance limited to the concert hall or a vinyl record was now available at the press of a button. The juxtaposition of high culture with the vulgar, violent narrative redefines our approach to this classical music. It becomes the wallpaper to our lives, particularly Impressionist classics from Debussy and Satie. Big name loadbearers like Bach and Mozart make an appearance (similar to Evangelion). We are reminded of Hiromi’s father stuck in his apartment playing with a model train, while his daughter criss-crosses Tokyo’s rail infrastructure to meet strange men on the street, near the tracks, or outside a phone booth. Our postmodern condition is marked specifically by our alienation from the mechanical and industrial. Neither the violin nor the railroad are understood through performance or physical contact. As with our sexual desires, they are again mediated through increasing layers of abstraction.

Does Anno have any thoughts on how to counter this despair? The film ends with Hiromi’s dream. In which… she again holds a camera. Despite the violence, the threats, and the fear, Hiromi has a vision of continuing her filmmaking project. The girls walk ankle-deep in a sewer to the tune of a pop song. Perhaps, rather than shrink away from the danger, Anno teaches us that the only way through is to continue our work. Even if it means trekking through the sludge (or, slop). Anno's commentary is neither moralistic nor celebratory towards digital video. It is, as all of his work is, rooted in a deep empathy that finds a spark of hope within a pit of blue-black despair. We’re reminded of Hiromi and her friend crying after watching a documentary on The Diary of Anne Frank. The only way truth (and, in particular, the truth of being a young woman) can counter the forces of destruction, degradation, and despair: To share our own stories by crafting resplendent and compelling images.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider becoming a patron of Hyperreal Film Journal for as low as $3 a month!

Akshaj is a writer-director from Dallas, TX. He's a lover of American popular music, New Queer Cinema, and global animation. Anything, really, to do with misfits, miscreants, and mise-en-scène.