TIFF '25: Sentimental Value

We first meet Sentimental Value’s protagonist in a fit of stagefright. Nora Borg, played by Renate Reinsve in her third collaboration with writer-director Joachim Trier, is moments away from the debut of her newest play, but preshow nerves have her in a state of mania; she’s dodging the exasperated stage manager, tearing at her costume, demanding that another actor slap her—the latter of which snaps her into the composure needed to deliver a performance received with calls for not one but two encores.

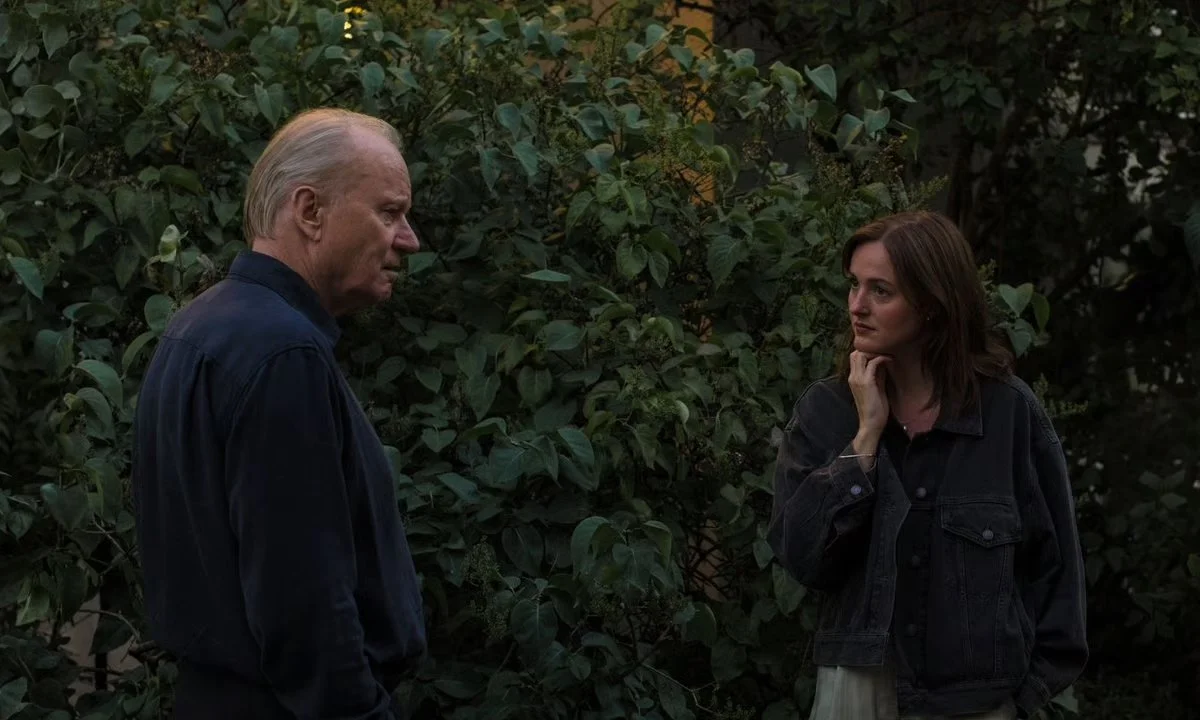

It’s a snapshot of a woman in turmoil and a bracing introduction to the film’s ideas of the roles we play in life and the dichotomy of public and private faces. Nora’s able to snap out of her imminent breakdown and present composure onstage, but her personal life is far less easily compartmentalized. At her mother’s wake, held in the beautiful, expansive old house she grew up in with her sister Agnes, Nora is confronted with the appearance of her estranged father Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård), a film director whose fame has faded over time. He’s there in part with an ulterior motive: to ask Nora to take the starring role in his latest screenplay, one he clearly hopes will lift him out of obscurity and back into the public eye. Nora scoffs at the thought and thinks nothing will come of it—but finds herself proven wrong when Gustav discovers his lead in Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning), a young American celebrity with the influence to snag Netflix’s money for the production.

There’s a multitude of larger-than-life characters at work here, and Trier and frequent co-writer Eskil Vogt do well to flesh them out into multidimensional characters whose storylines are gracefully balanced. There’s Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas), who as a child had a starring role in one of her father’s films and an opportunity to bond with him in a way Nora never did. She’s the younger sister, but where Nora once protected her from their parents’ loud and angry divorce, Agnes—who’s built a career as a historian and a family of her own—is now the one worrying over Nora, who self-isolates out of deep inner self-loathing, having affairs with married men to avoid real intimacy and rebuffing her father’s attempts at reconciliation.

Skarsgård is at the top of his game as he portrays an aging and arrogant man dealing with feelings of displacement. In any given scene you’ll wince at Gustav’s boorish comments and feel a sharp sting of pity at his ungraceful attempts to mend his broken relationships with Nora and Agnes. As production on his new movie begins, Gustav is determined to hire a cinematographer he worked with closely on his past films; when he visits this old friend, he finds a man so frail he can barely stand up by himself. Without words, Skarsgård shows Gustav’s dawning realization of how far away his past actually is. It’s the perfect window into his point of view as a man struggling both to write his legacy and come to terms with the fact that he abandoned his own descendants in favor of his artistry.

The crux of the movie is the relationship between Nora, Gustav, and Agnes, and it’s brought to life with both Trier and Vogt’s deeply thought out family dynamics and the real chemistry between Skarsgård, Reinsve, and Lilleaas. Reinsve delivers a revelatory performance as Nora, making it painfully easy to see the deep emptiness and loneliness she holds and can only transmute on stage. In one scene, Nora describes her own artistic process of inhabiting her characters completely in order to discover their true selves; on stage, we see her more emotive and alive than in real life, transmuting those emotions. In another, she abruptly leaves her sister and brother-in-law’s apartment after spending an evening with them and their son. There’s no explanation, but we can tell through Reinsve’s guardedness that she’s overwhelmed with this confrontation of what she doesn’t have: easy intimacy, vulnerability and openness.

And there’s an added dimension of broader family history that pieces together both the past and present in the film. That old house Agnes and Nora grew up in acts almost as a secondary character. It’s the foundation for the move itself, a set piece for Nora’s childhood and adulthood, the stage for Gustav’s movie, and, as we later learn, the house he grew up in as well. Gustav’s movie is semi-biographical, telling the story of a young boy whose mother kills herself. Via flashbacks shown in the style of home-video footage and clips of Agnes’s own archival research into her grandmother’s history, we learn about her arrest and time in a concentration camp in then-Nazi-occupied Norway—a time she never spoke about after. Gustav won’t admit it, but his screenplay is an attempt at understanding his mother’s choice and resolving that childhood trauma. It’s through his script that Gustav finds it possible to communicate, and it’s here we see how both he and Nora seek refuge through the intermediary of performance.

These admittedly heavy topics don’t weigh the movie down, as Trier and Vogt inject humor and good-hearted sentiment throughout. When Gustav is walking Rachel through his house for the first time, laying the groundwork to convince her to take the role, he shows her the room where his mother hung herself—even pointing out the stool she used. “The one we got from Ikea?” Agnes asks him when he tells her later. And as Gustav interacts with Rachel’s Hollywood and Netflix connections, there’s a playful setup of the old versus new in cinema and their inherent dichotomy.

Near the end of the film, there’s a scene with Gustav, Nora, and Agnes’s faces transposed over each other, fading in and out. As the most surreal shot in the film, it’s an indelible visualization of their inextricability—and a mark of Trier’s success in creating an intergenerational story of art and personal history.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider becoming a patron of Hyperreal Film Journal for as low as $3 a month!

Alix is the editor-in-chief for Hyperreal Film Journal. You can find her on Letterboxd at @alixfth and on IG at @alixfm.