Stories Like Ours: On Irrfan Khan and THE NAMESAKE

THE NAMESAKE—Mira Nair’s moving and visually rich film adaptation of the Jhumpa Lahiri novel with the same title—empathetically portrays the particular kinds of loss, loneliness, and longing experienced by immigrant families. In many ways, the narratives of the South Asian characters in the film are stories playing out within my own family. A century after a previous generation came to the Caribbean from northern India, my immediate family moved to the United States (in 2001). From there, we would begin rebuilding our lives while navigating spaces in which we were the only people like us.

As I get older, I am increasingly grateful to see so much of my emotional journey reflected in the images and characters in The Namesake. Some moments feel like extractions from my own upbringing while others resonate as dreamlike projections of what might have been.

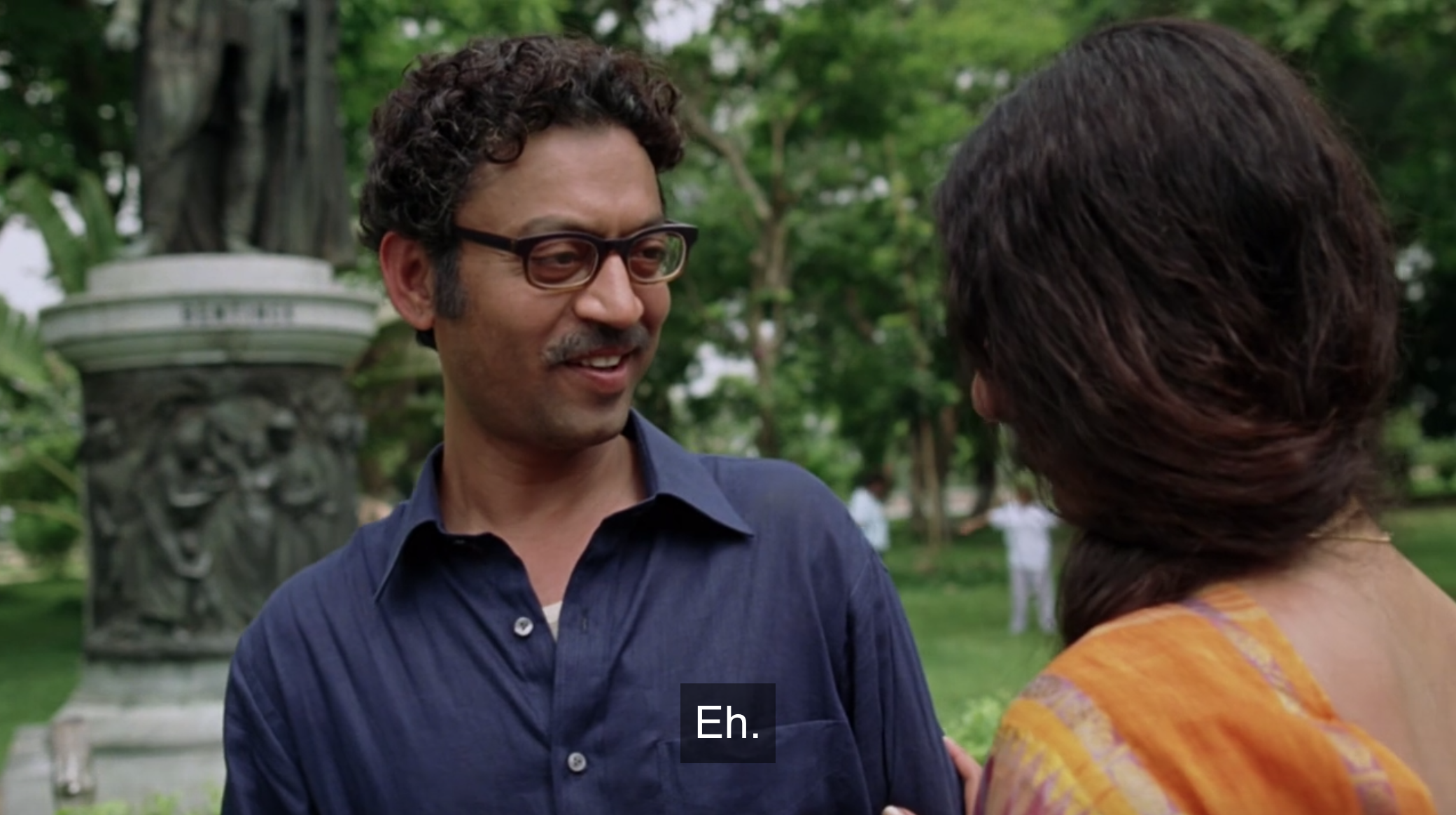

The late Irrfan Khan’s performance as a compassionate husband and father named Ashoke Ganguli stands out as an example of pure vulnerability on screen. I am deeply saddened by his passing and grateful for the understated humanity he brought to this character. Throughout the film, his ability to command the screen while saying and doing just enough was almost magical. Being able to revisit such a tender portrayal of South Asian masculinity within a fictional family that looks and feels like mine continues to be a gift. I spent years feeling like I was too sensitive, quiet, and anxious while constantly receiving signals that I needed to become more hardened, aggressive, and guarded. There was rarely space for me to feel things or express those feelings in the moment. Ashoke Ganguli is a model for the kind of paternal influence I didn’t know I needed until fairly recently. He is also a model for a way in which we can approach human existence with unflinching kindness.

Irrfan’s take on Ashoke blends intellectual curiosity, playfulness, and love with transcendent depth and wisdom. While my father mostly had the best intentions during my more fragile years, I’ve only ever known him to be emotionally distant and withholding. As a child, I was constantly fearful and eventually defensive whenever we interacted. He—like many of the men I grew up around—was conditioned to be closed off. I don’t know how things have changed on his end but I’m no longer directly impacted by his refusal to be vulnerable. Ashoke Ganguli gives me hope that I can do things differently and love others more completely.

Kal Penn plays Ashoke’s son Gogol in the film. His character is named after the Russian author Nikolai Gogol because his father was in possession of one of his books—The Overcoat—when he survived a train crash as a younger man. Gogol hates his name because it only serves to further complicate his split existence as a marginalized kid trying to navigate new surroundings while grappling with his family’s traditions. He sees his parents as forces working against his happiness. Even though I can now understand Ashoke’s struggle to connect with his son, Gogol’s unhinged anger is exactly what drove most of my behavior during my teenage years. After we moved to a largely white and conservative Texas suburb where the pronunciation of my last name was often a joke, I felt like I had been placed somewhere under circumstances that only made me feel more alone.

In a particularly heartbreaking scene, Ashoke gives Gogol a copy of The Overcoat as a gift and tries to tell him why the name means so much to him. It’s because Nikolai Gogol spent most of his life away from his homeland, just like Ashoke. Irrfan Khan’s longing looks, subtle movements, and deliberate restraint make us feel the ache of a parent trying to bridge a generational divide. For the majority of this scene, Gogol is blasting music and not engaging with his father. He is grumpy, confrontational, and prematurely defensive while Ashoke simply observes him. My father and I would likely be screaming at each other in a situation like this.

Even though it seems like a pleasant alternative to have a father who would approach things more sensitively, the theme of withholding still holds true. Ashoke stops just short of telling Gogol exactly why his name is so significant, opting instead for even more longing looks and the slightest touch to let his son know he is there. As difficult as Gogol is being, I understand the flustered eagerness of wanting a parent to simply say more. Irrfan Khan’s ability to place me in the mind of the parent in this situation has taught me quite a bit. Every immigrant parent is simply another individual human being who may be suffering silently in ways they are afraid to tell their children. Talking to each other can take lifetimes.

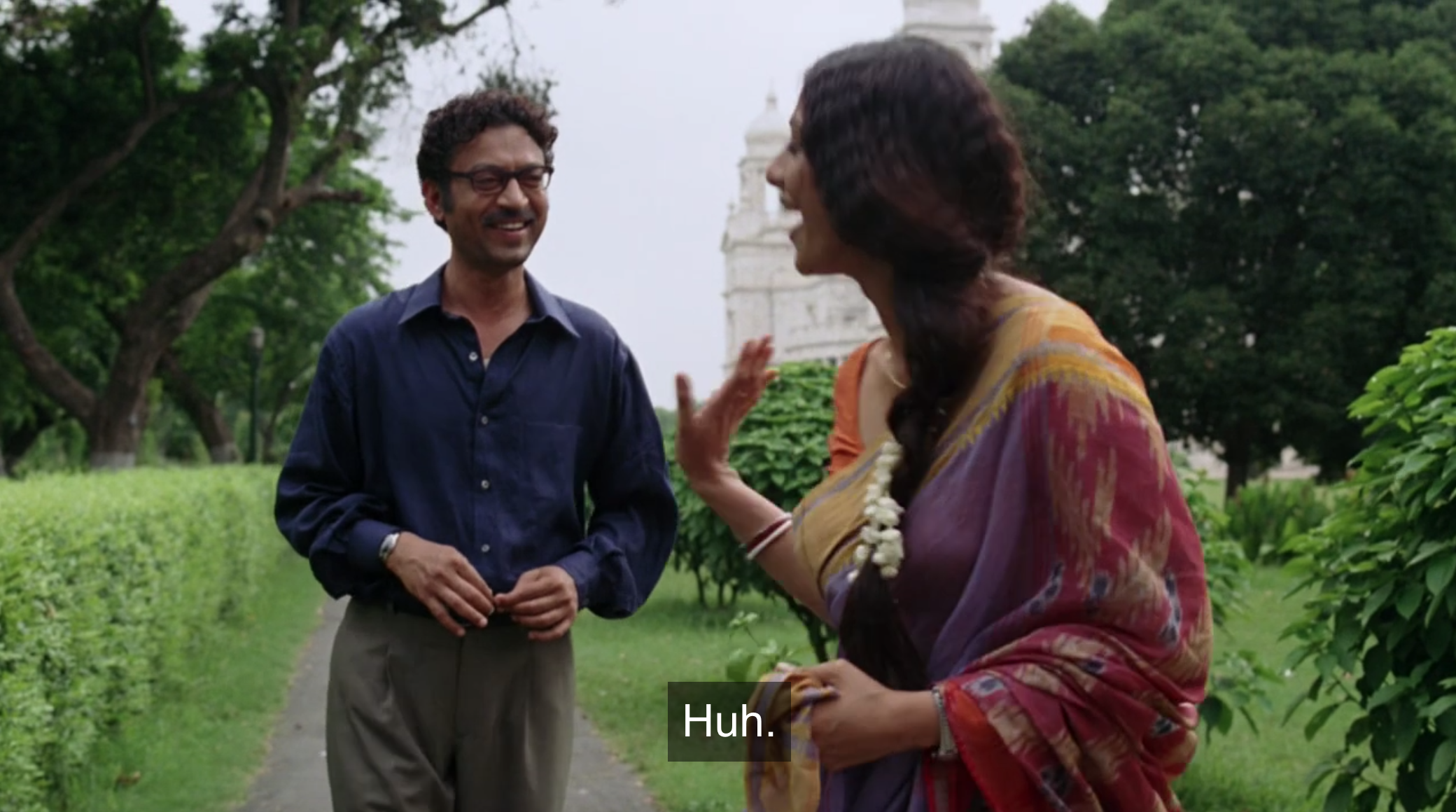

The first part of the film tells the story of how Ashoke meets and marries Ashima (played wonderfully by Tabu). These early scenes focus on the individual struggles of two people who have left their homeland to make their dreams come true in a place that will always feel a bit stifling. They are just as sad and angry as Gogol and his sister will be later, but these children will never truly know what their parents went through to give them a better life. I am likely just as guilty of pointing fingers and labeling situations as explicitly harmful without truly understanding how and why my parents came to be the people they are.

Shortly after their wedding, Ashima is left alone in a small apartment in a new country while Ashoke goes to work. She tries to build routines that make sense in her new setting while navigating the reality of a marriage that was arranged. I appreciate that the relationship between these two people is portrayed as something undeniably messy but unwaveringly kind. Irrfan Khan’s caring nature and unique sense of humor fill what could easily be scenes of insurmountable struggle with intimacy and closeness. It’s always clear that Ashoke and Ashima are there for each other. This contrasts the tumultuous years my brother and I experienced while our parents figured out how to be good partners to each other and good parents to us in a place that was not home. Seeing people like me find and nurture hope while living in a strange place helps me imagine a less tumultuous future for myself.

In a particularly beautiful shot, we see Ashima’s silhouette waving goodbye to Ashoke as he vanishes into the distance and heads to work in the snow. She is saying goodbye to the only thing anchoring her in her new life. The composition of the shot foreshadows the pivotal event that will drive the actions of Gogol and Ashima during the film’s final act—Ashoke’s sudden passing.

Perhaps I chose to revisit The Namesake in the immediate aftermath of Irrfan Khan’s death because it gives his character a complete life story without compromising his dignity or emotional complexity.

Ashoke Ganguli exemplifies much of what made Irrfan a great artist, but the truth is that he was much more than just this role. It’s clear that Irrfan Khan had a tremendous impact on the Bollywood community and that he cared deeply about where he came from. This was someone who was very important to millions of people before I was ever moved by his work on the screens in my immediate vicinity. He was fairly established in Hollywood, too—even if that troubled industry could only offer him the roles of one-dimensional sidekicks and villains.

It’s always interesting to see what calls you back to where you came from. Irrfan Khan may have felt as displaced in the United States as my family and many Indian immigrants continue to feel. This reinforces the urgency for me to get more familiar with art that is removed from a strictly Western gaze. Irrfan is a symbol of how a person can bring their full self to an enriching life and touch the lives of many while refusing to compromise on their values. To do these things with one’s humility intact feels like the most we can hope for while on this plane of existence.

Throughout The Namesake, Irfan Khan and Tabu are playing two people in love. This is understood, but it’s rarely acknowledged out loud. At one point in the film, Ashoke vulnerably reveals his longing for Ashima to say "I love you." She asks if he wants her to do that "like the Americans do” and the interaction concludes playfully. Her light treatment of this request is affectionate but ultimately a bit of a deflection and an acknowledgment that such overt gestures aren’t common or comfortable among South Asian people. It’s as though the expression of needs and feelings is an indulgence.

Yearning for undelivered expressions of love from partners and family members is something I’ve clumsily navigated for many years. It’s a wound from childhood that left a chasm I often fill with unhealthy coping mechanisms. My family doesn't vocalize love so much as demonstrate it with things like financial security. They are much more comfortable keeping things external while I’ve always needed something more authentic.

It’s significant that Mira Nair and Irfan Khan decided to include a scene in which Ashoke bravely acknowledges a basic human need grounded in a specific cultural context. How fitting that a singular presence like Irrfan’s would convey something so quietly radical. It’s the kind of immigrant narrative worth witnessing more frequently and one that may have changed how I felt about my entire life had I encountered it sooner.

Nick Bachan is a writer and illustrator based in Texas. His essays, cartoons, and stories explore how people engage with emotions, history, pop culture, and one another.

@nickbachan on Twitter // https://nickbachan.com/