The Mastermind: Kelly Reichardt’s Nod to New Hollywood Heist Capers

Kelly Reichardt’s latest is a flickering shadow of a heist flick that echoes the films of the era it depicts, the early 1970s. Melding the shaggy dog atmospherics of New Hollywood anti-thrillers like The Long Goodbye to her own inimitable style, The Mastermind drops us immediately into the auteur’s carefully observed mundanity. Many of us have spent time in a quaint local museum with sleepy guards and chattering children, but not quite as they appear in this film.

The kids belong to J.B. Mooney, an unemployed father of two boys and son of a local judge. Mooney is a privileged guy who doesn’t seem to have endured many consequences for his actions, or lack thereof. When his father compares Mooney’s open schedule to that of a more successful peer, he dismisses the basic idea of running a business as [I’m paraphrasing here] “no way for a person to spend their time.”

Separately, he manipulates and lies to his mother to borrow money. “Your father and I want to retire,” she scolds him, while dutifully digging out her checkbook. The money isn’t for carpentry supplies – it’s to pay off three schmucks to do the legwork of stealing four paintings from the local museum, which Mooney cased in the opening scene under the guise of a family outing. (The paintings of interest are real works of art by American modernist Arthur Dove.)

Reichardt’s technique is so subtle it takes awhile to realize the story is a period piece. (The vibe is helped immensely by the casting of Alana Haim – the closest our era has to 1970s weird girl icons like Shelley Duvall – as Mooney’s wife.) Although thoroughly grounded in the small-town milieu of Framingham, Massachusetts, the film eventually hints at greater American struggles. A Confederate flag hangs in the museum. Posters and visual commentary on the Vietnam War and Black Power speckle the film’s public spaces. As in Reichardt’s second feature Old Joy, dreary news reports hiss like static in the background, conjuring ambient dread.

But Reichardt’s tragicomic approach tends to fog over any overt political commentary. Despite her employ of Black Power iconography, the story isn’t particularly interested in the lone Black character, one of Mooney’s accomplices, once his role in the plot is complete. Instead, the historical signposts rub uncomfortably against the film’s unlikeable, white beta male protagonist. This is surely on purpose. Is Reichardt commenting on the modern discourse of economic unease leading young men to drift into grift? One character actually says “Weird times, huh?” as if to clue us into pondering similarities between the stagnant ‘70s and today.

Played by Josh O’Connor, Mooney is a curious antihero, not above using his father’s political influence to squeak through uncomfortable meetings with cops, but otherwise inert. O’Connor is not given much to do besides stare into space while his plans go awry, and occasionally wince, but this seems to be part of the fiendish irony implied in the film’s title.

Reichardt’s work has ranged from emotionally wrenching minimalism (Wendy & Lucy) to a real-deal thriller with bombs and murders (Night Moves). She seemed to lose perspective in her last film, Showing Up, which pitched an artist’s everyday frustrations as Herculean struggles. Although the film may have drawn a new audience to her work via Outkast’s André 3000 in a supporting role, it’s one of her rare misfires, with the depth and presence of cardboard.

The Mastermind is a welcome return to higher stakes storytelling, with surprising splashes of slapstick comedy. Reichardt establishes a sly “things won’t go well” vibe early on, and front-loads the film with entertaining hijinks, bolstered by jazz legend Rob Mazurek’s percussion-heavy score. It’s also a great-looking movie – Director of Photography Christopher Blauvelt achieves the patina’ed glow of iconic 1970s films shot by Gordon Willis.

Due to a tiny theatrical window (it’s distributed by streamer Mubi), The Mastermind may not be available on the big screen by the time you read this. Still, it’s a welcome addition to Reichardt’s body of work, with a haunting conclusion that crystallizes her enduring observations on class, privilege, and the state.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider becoming a patron of Hyperreal Film Journal for as low as $3 a month!

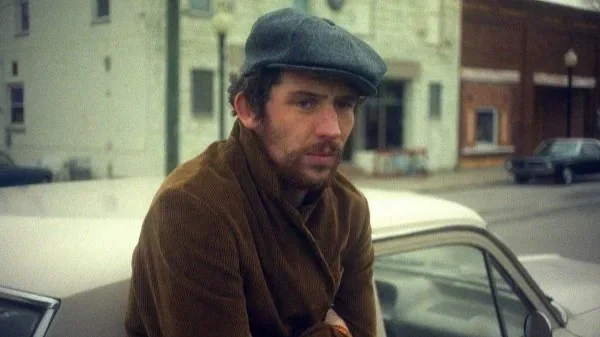

Matthew K. Seidel is a writer and musician living in Austin since 2004. The above selfie was taken in an otherwise empty screening of Heat at 10:30 in the morning. You can find him on Letterboxd @tropesmoker.