The Struggle is Real: Alec Guiness in The Horse's Mouth (1958)

At its heart, the 1958 British film The Horse’s Mouth directed by Ronald Neame is a movie about art. More specifically, it's a movie about the Art Life. Its protagonist, played by Alec Guiness (who most Americans shamefully only know as Obi-Wan Kenobi from the original Star Wars trilogy) is one Gulley Jemson, a caddish loaf who quickly swindles his way into a wealthy London couple's penthouse, only to immediately destroy it in the pursuit of his next work. The apartment quickly attracts an entourage of various other artists, roustabouts, and wannabes who descend and help complete the destruction. In the traditional sense, Jemson is a complete moral degenerate, taking advantage of an elderly couple's generosity for his own selfish aims. However, where I think the movie shines is in its honest depiction of the poverty and desperation that underlay what it means to be an artist in a capitalistic society.

Jemson lives on the verge of poverty. He lives in a house boat, (not today's luxurious kind, but the kind most often associated with London’s water gypsies). He’s greeted warily in all the haunts and bars of London’s lower classes, as he’s the kind of man who’s already used up his supply of goodwill from most of the people in his life. You can tell that there is a string of broken promises and failed relationships, romantic and otherwise, trailing behind him, but still he manages to finagle his way into the house of some wealthy patrons called the Beedles, and the first time Jemson meets the Beedles you can just feel the disgust and loathing toward these perfect pictures of British wealth and propriety radiating off of Guinness. They are the spitting image of the British upper class, with their overstuffed Victorian apartment, Mr. Beedle’s monocle, top-hat, and tuxedo, and his wife’s incredibly superfluous hobby in the arts. Like much great British art, the contrast of the class divide in this movie is stark.

Jemson then engages in the perpetual artist's struggle of having to humor and flatter a bunch of rich philistines in order to get his work made. Mrs. Beedle fancies herself an amateur painter and shows Jemson a bit of her work to evaluate. You can briefly see the anguished look on Jemson’s face as he confronts Mrs. Beedle's atrocious painting, but he plays it cool, quickly steadying himself before commenting that it shows an “interesting perspective.” Having passed the test, he can now move on to discussing using the Beedles wall to paint his next piece.

Another subplot follows a young art student who follows Jemson around begging to be his apprentice, as Jemson is actually somewhat well known in the art scene and has had a modicum of success. Jemson waves him off, to which the kid replies “I really want to be an artist!” to which Jemson responds, “so does everybody, then you grow out of it.” This is the core of the movie to me. You see poor, desperate Jemson living in squalor, lying, cheating, and screwing people over, as he goes through a lifetime of heartache and disappointment all in the pursuit of this one singular desire he has to create and express himself. Yet, he still doggedly pursues it knowing the sacrifices that it has taken to even get him to this modest position. It’s beautiful.

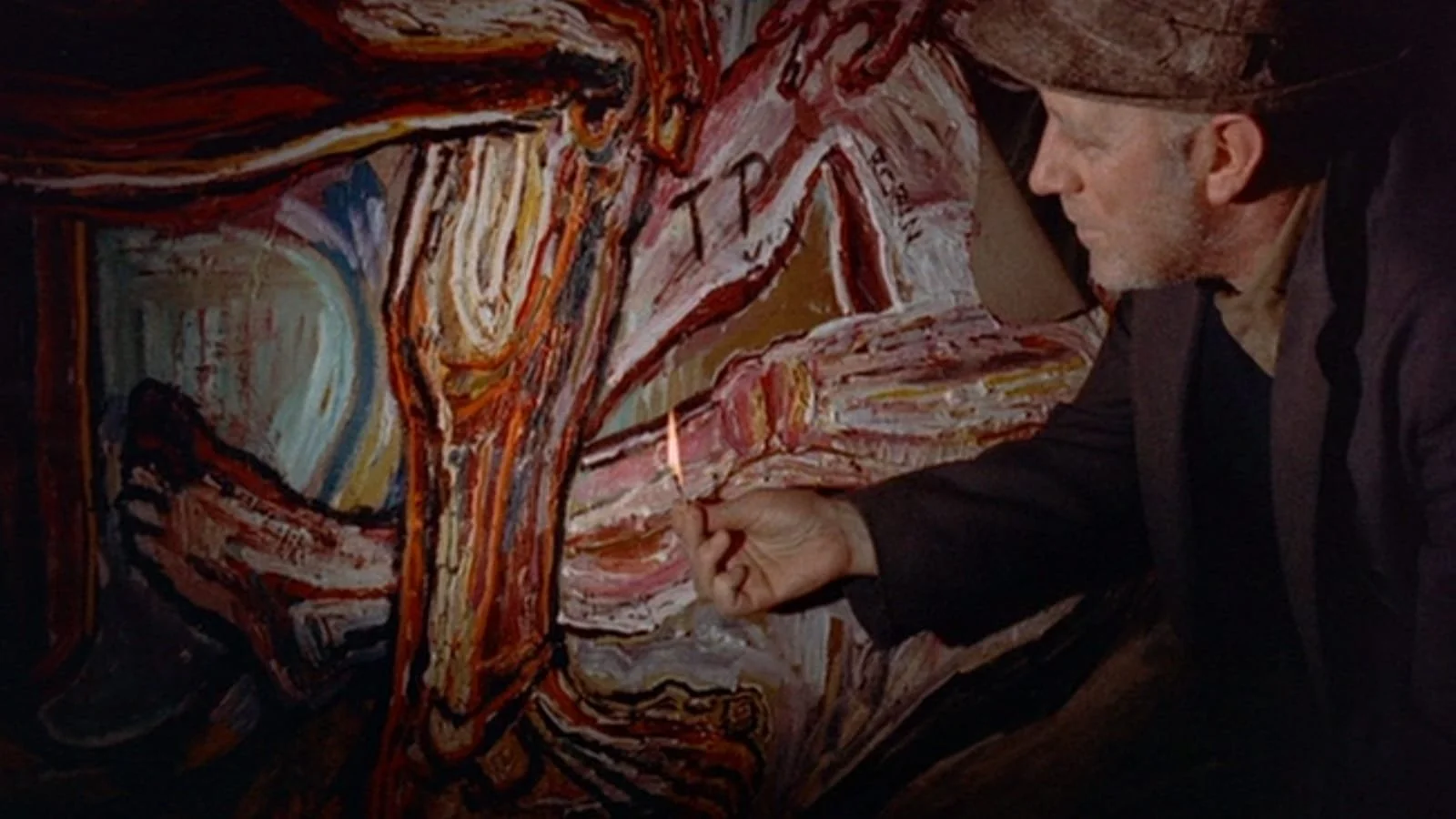

This love letter to art is continued in the last act of the movie. It revolves around Jemson creating a massive mural on the side of a ruined church that is set to be demolished by the city. The setting really adds to the film here, as London in the late 1950s is in a transition stage. It’s past the Blitz, but not yet to the revitalization of the Swingin’ 60’s. Rubble and construction still stain the cityscape, but it’s on its way towards modernity, and this church demolition is a part of this redevelopment that will eventually lead to the city of today. Dozens of people pitch in to help him realize his goal and add their own creative texture to it. It is now bigger than Jemson, a community expressing itself, strangers finding each other in the city to achieve a common goal against the city's stated objectives. I won’t spoil how it ends, but it is appropriate. To me, it expresses another aspect of the art philosophy of this film. By creating a mural, Jemson and the community are staking a claim on this piece of the city. They are trying to hold on to a piece of Old London in the face of redevelopment. It shows how art can be used as a political act, but also how humans can make an ultimately futile attempt to make a permanent lasting impact on a world defined by constant change.

Overall, I love this movie. It is so compassionate and big hearted towards its subjects while maintaining an eye on the real heartbreaks and sacrifices that they have to go through. If you are a creative or are thinking of becoming a creative, I would absolutely give this one a watch. Underneath all of the wacky hijinks (and it has its fair share) it is a surprisingly sophisticated movie that comments on everything from the class divide, to art as a political/community act, to a deeper philosophy of art and life itself. I came away feeling motivated to be creative myself, and I think that in a world that so rarely cultivates that value or impulse, it is a very important film to watch. And also Alec Guiness!

If you enjoyed this article, please consider becoming a patron of Hyperreal Film Journal for as low as $3 a month!

Andrew Turner is a writer based in Austin, TX. He draws his insights on film from his background in History and Political Science and is interested in how these intersect with each other. He has lately been writing about 20th century history and film, particularly of the Eastern bloc. He also has an interest in his own native central Texas, its politics, food, economy, and cultural output. He recently wrote about the rise of Austin to its current status as a major technopolis. He has written for the Austin Chronicle, The Quorum Report, and also can be found on substack.

https://andrewturner.substack.com/