Obayashi Times Two: A Poignant Retrospective

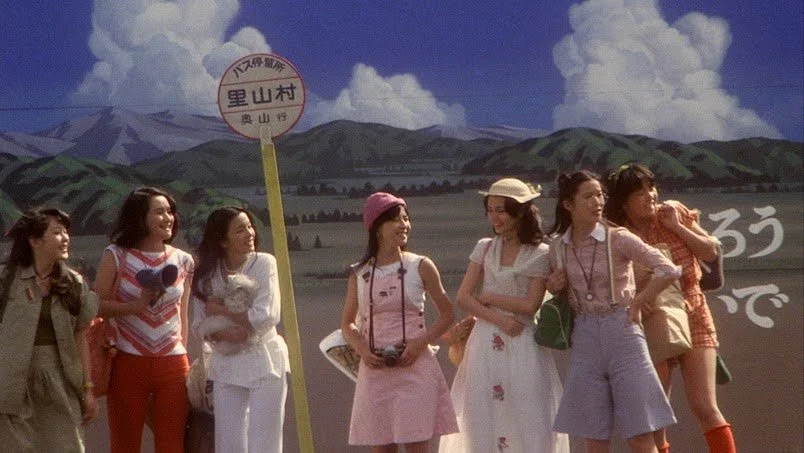

Chaos in cinema has many, many faces. Sometimes it’s a haunted house that devours young women in candy-colored hysteria, sometimes it’s a summer romance that dissolves into memory, and sometimes it’s the feeling of being out of step with time. Nobuhiko Obayashi, best known for his cult debut House (1977), built his reputation on the first version of chaos: a pop-art, kaleidoscopic heavy, absurdist horror-comedy that feels like cinema’s version of shedding. But this summer, Austin Film Society presented a retrospective of Obayashi’s work for an opportunity to experience the director's complex perception of chaos. Two of his most remarkable works—The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (1983) and His Motorbike, Her Island (1986)—show us a different kind of Obayashi: a director with pizzazz that carefully replaces House’s frantic style with something quieter, stranger, more human. Where his debut consumed its characters in gory spectacle, these two films let their characters slip away into the fog of memory.

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time adapts Yasutaka Tsutsui’s sci-fi novel, focusing on a schoolgirl, Kazuko, who gains the ability to leap through time after a strange accident in her science lab. Although the film is set up narratively as a fantasy adventure, Obayashi instead illustrates somewhat of a drifting daydream. The leaps themselves are not blockbuster-y set pieces but sudden, disorienting shifts, leaving Kazuko unsettled rather than empowered. Obayashi avoids explaining the mechanics of time travel. Instead, he lingers on Kazuko’s interiority: how her friendships change, how she struggles to articulate feelings that always seem one step out of sync.

This is where the film’s real insight lies. Adolescence itself is a kind of time travel: one moment you’re too young, the next you’ve aged too fast, always skipping ahead or falling behind in ways you can’t control. Kazuko’s gift becomes a metaphor for what every teenager feels. Life is happening at an inconsistent speed and the surrounding world refuses to align with your emotions. Rather than emphasize spectacle, Obayashi emphasizes atmosphere (similarly to House). He focuses on classrooms bathed in quiet light, long silences that stretch just a bit too long, landscapes that seem impossibly vast. The science fiction here is not a puzzle to be solved but a lens for understanding how fragile memory and experience really are.

Three years later, His Motorbike, Her Island arrived with an equally interesting premise. Ko, a young man intoxicated by the speed of his motorbike, meets Miyo, a free-spirited girl from a small island. They fall in love, ride together, and imagine futures that are doomed to slip away with the season. On paper, it’s the most conventional of summer romances, a coming-of-age bonanza. But Obayashi transforms it into something unequivocally haunting.

Much of the romance is filmed in black and white, which initially reads as nostalgia. But color flickers in at unexpected moments, redefining what we’re seeing. The alternation between colors refuses to let the film settle into either pure realism or fantasy. Instead, it evokes how memory actually works: certain details burn brightly while others fade, sometimes within the same instant. By shifting textures mid-scene, Obayashi makes us feel the instability of Ko and Miyo’s love, its beauty and its inevitable fragility.

In The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, the vanishing act is internal. Kazuko loses her grip on ordinary life as time loops and fractures around her. In His Motorbike, Her Island, the disappearance is romantic. Ko and Miyo’s relationship flickers like a memory we can’t quite hold. Both films suggest that youth is something inherently unstable, doomed to dissolve, whether through inexplicable metaphysical traveling or the simple passing of seasons.

What separates the later films from Obayashi’s debut film is their tenderness. House revels in grotesque chaos, its girls turned into punchlines as much as victims. By contrast, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and His Motorbike, Her Island are deeply empathetic. Both films slow down to watch characters sit in silence, hesitate, struggle to articulate themselves. When Kazuko leaps through time, the disjointed images feel like extensions of her confusion. When Ko and Miyo ride the motorbike together, the layering of sound and image mirrors the intoxicating blurriness of first love.

These films also oppose casual, calm closure. The Girl Who Leapt Through Time does not end with Kazuko mastering her powers; it leaves her caught between knowledge and uncertainty. His Motorbike, Her Island does not tie up Ko and Miyo’s romance with a neat bow; instead, it drifts away, as though the story itself has already been half-forgotten. Both endings insist on openness, on the idea that life rarely delivers the resolutions we crave. If House (literally) consumed its characters in spectacle, these films let their characters slip away into the gaps of memory.

Placed in the context of Obayashi’s career, they feel revelatory. After House, Obayashi could have been trapped by cult expectations, endlessly repeating surreal horror. Instead, he changed course and found chaos not in spectacle but in the human condition. His reputation abroad may still lean heavily on the spectacle that is House, but in Japan, films like The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and His Motorbike, Her Island helped define him as a director of romance, adolescence, and memory. They remind us that his artistry was not about style alone but about using style to articulate the instability of life itself.

Obayashi died in 2020, leaving behind a vast and varied body of work. But for those who only know him through the chaotic brilliance of House, these two films are the perfect invitation to see a beautifully complex side. They show him not only as a Japanese horror icon but as a genuine filmmaker of rare sensitivity, someone who understood that the greatest chaos is not supernatural but human: the fact that time moves on, love fades, memory falters, and yet we go on living anyway.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider becoming a patron of Hyperreal Film Journal for as low as $3 a month!

Manny Madera is a tech writer by day and Hyperreal Film Journal editor by night. Most of his free time is dedicated to watching East Asian and Latin American films or writing personal plays. He is currently based somewhere in Austin, TX.