HANDS ON A HARDBODY: A human drama thing

“It’s a human drama thing. And it’s more than just a contest. And it’s more than just winning a truck.”

Rating: 🤠🤠🤠🤠🤠

[TRAILER]

[FIRST 9 MIN]

Competition makes me uncomfortable. It always has. Like most, I don’t like the feeling of losing. But winning often doesn’t feel much better. There’s been many a time when I’ve found myself the winner of a board game with friends, feeling like I’d just wasted everybody’s time but my own. There have been times when I’ve watched a too one-sided stomp of a basketball game and felt so sorry for the fans of the losing team. Realistically, where there are winners, there have to be losers. Call me soft, but that sentiment is not the easiest for me to stomach.

Yet, despite my uneasiness around competition, or maybe because of it, S.R. Bindler’s 1997 indie doc classic Hands on a Hardbody, about one of the most grueling competitions I’ve ever seen, is probably my favorite film of all time. It’s at many points very funny, at several points quite tragic, and all at once an inspiring and well-meaning look at how far some people will go in attempting to further their station in life, and the many failures and few successes that come with such attempts.

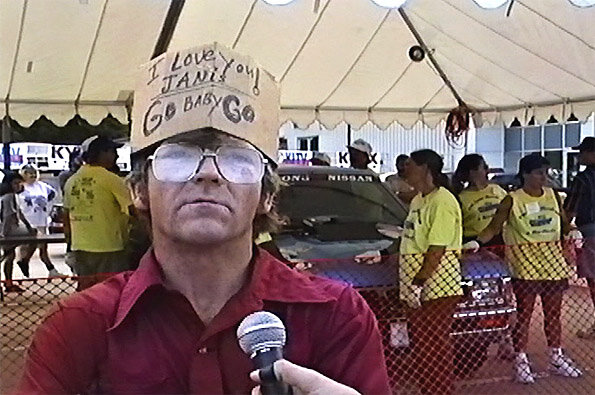

The film was made by a crew of film school graduates on the lowest of budgets, shot on a couple of Hi8 cameras, making it by no means the prettiest of films. But where it lacks in fidelity, it excels in its narrative, built via a combination of exceptional editing chops and what appears to be a deliberately openhearted approach to documentary filmmaking. The premise of the film is this: It’s 1995 in Longview, Texas. The local Nissan dealership is hosting its annual Hard Body contest, in which 24 contestants are pitted against each other to see who can keep one of their hands on a pickup truck the longest. The last person with their hand on the truck gets to take it home. By the end, after multiple days of boredom, sleep deprivation, knee pains, and hallucinations, there will be 24 people sent home and only one person among them with anything to really show for it.

Whereas the contest is cruel and dangerous, a publicity stunt at the expense of multiple people’s health and well-being, the film never feels as exploitative. It is clear that the filmmakers were deeply fond of the cast.

They are eccentric and endearing, a crew of Texans from a small-town community that rarely draws attention from filmmakers or popular culture in general. There’s the veteran Benny Perkins, who after winning a previous year’s contest, is now keen to some grander truth about the competition, often philosophizing about it as a metaphor for life, morality, and the human condition. There’s Norma Valverde, a Sony Walkman-clad devout Christian, who believes it’s God’s will that her family wins the truck, and who may serve as visible, onscreen proof of an instance of when the Holy Spirit has entered a person's body. There’s my favorite competitor Ronald McCowan, whose approach to the competition is so plainly misguided but whose immense self-confidence and charisma makes me briefly believe that maybe his methods aren’t as self-sabotaging as they clearly are. And there are 21 others, real people, each with their own idiosyncrasies, and each with their own motivations for entering the contest.

Surprising is that in spite of being direct competitors, the contestants form friendships, give each other advice, and show sadness when a rival competitor eventually gives up. Their competitiveness seems to be the real-life manifestation of that pep talk many pee wee coaches give: “It doesn’t matter if you win or lose; it’s all about having fun and making friends.

But that’s the thing. Unlike in pee wee soccer, here the difference between winning and losing is so drastic, with potential life-changing outcomes. So why help each other? Why mourn a competitor’s departure when it only improves their own chances at winning?

I think it’s because although all of their lives would be substantially bettered by winning the truck, they are all very aware that it would do the same for any one of their competitors. I think this awareness manifests itself in a very real sense of solidarity and respect between all of them.

It’s the most Texan film I’ve ever seen. I think it’s probably the most American film I’ve ever seen. It’s tragic, but oddly hopeful and poignant. It’s a story about a working-class group of people, all trying their best to survive in a ruthlessly capitalist society that too often puts people in me vs. them, winner-takes-all situations. It’s a story about the social inequities faced by members of small-town or rural communities, their day-to-day struggles rarely displayed so clearly or prominently as they are here.

It’s sobering, in a way. By the end, there are no signs of substantial societal progress; there are no inequities being meaningfully amended here, no capitalistic values being overthrown. Twenty-three people lose. Only one person wins. And the world seems very much the same as it was at the beginning of the film. But what’s also clear is that even in the direst of competitions, compassion and sincerity can exist. The Hands on a Hardbody contestants might not be able to escape this winner-take-all world, but at the very least, they can struggle through it in solidarity and do their best to elevate their competitors, rather than knock them down.