It's Been the End of the World: 28 Years Later

The year is 793 AD. It’s the end of the world.

You are a young monk on the isle of Lindisfarne. You live a quiet life of scholarship and contemplation. On a windy morning in the early summer, you look to the northern seas. In the distance, a flash of lightning - a storm is coming. The wind will bring a fleet of Viking longboats. The Vikings will set fire to the monastery and slaughter your brothers and smash your holy relics. The altar will run red with blood.

You don’t know it yet, but this is the end of your world. The Viking Age has begun.

The year is 43 AD. It’s the end of the world.

You are a Briton warrior. You stand on the banks of a river crossing, waiting for the Roman army to make their way up the Thames. You’re hoping to beat them back to the sea. You don’t know it yet, but you will fail.

This is the end of your world. The Roman conquest has begun.

The year is 1348. It’s the end of the world.

At Weymouth Harbor, a flea-bitten rat jumps off a ship from Gascony. Within two years, over a third of the country will lie dead.

This is the end of the world. The Black Death has begun.

The year is 1066.

Or maybe the year is 1914.

Or maybe it’s 1642.

Regardless, it’s the end of the world.

In 28 Years Later, the year is 2031. It’s the end of the world.

A small community of zombie outbreak survivors lives on the island Lindisfarne, linked across time to those long-dead medieval monks. The Lindisfarne survivors surround themselves with the detritus of the age of the British Empire, decorating their town with portraits of the queen and English flags. On the mainland, zombies roam the crumbling ruins of cathedrals. Everywhere we go, there are reminders of Britain’s past. It’s a neat way for director Danny Boyle and writer Alex Garland to remind us that on the British Isles alone, the world has already ended a hundred times. In fact, the world is always ending somewhere.

Depending on who you ask, modern zombie movies are about consumerism, or conformity, or invasion. All these things can be true, but I suspect the zombie movie also gets at a deeper, simpler anxiety. Notice the fleshiness of a zombie movie - the camera lingers on teeth gnawing through muscle and tendon, rotting limbs, mounds of corpses. It’s a primal fear: that we are, after all, just bodies. And it follows that if the body is destroyed, then we are destroyed.

Consider a scene you’ve probably seen a million times: character A loves character B. Character B becomes a zombie. Character C urges A to kill B, but A can’t do it. C gets angry, maybe shouts something along the lines of “B isn’t in there anymore!”. You, the audience, become bored and annoyed. Hasn’t A ever seen a zombie movie? The filmmakers have already made it abundantly clear that a zombie is no longer a person, so for the love of God just shoot B in the fucking head and get on with the story already.

28 Years Later suggests a much squishier dynamic. The zombies now form social units, led by ultra-strong, ultra-fast, and ultra-hung Alpha zombies. We see the zombies washing themselves in the river, fleeing danger, and giving birth. Are they not living beings in their own right? These zombies are not just dead meat.

Russian philosopher and critic Mikahil Bakhtin wrote about grotesque bodies in medieval art and literature. While these bodies were often ugly in proportion, busy eating, decaying, and shitting; they were not objects of fear or disgust. Bakhtin observed that the medieval body is always “in the act of becoming…moreover, the body swallows the world and is itself swallowed by the world.”

The physicality of the zombies of 28 Days Later hearken back to those grotesque figures of medieval art. Some crawl along the ground and gorge themselves on worms. The camera lingers on their rippling mounds of flesh and slobbering mouths. The Alpha zombies sport comically huge dicks. Boyle emphasizes the aliveness of his zombies, often cutting to footage of them seen through wildlife cameras, as if he was observing a new animal species. His zombies are always in motion and busy interacting with their world - eating, screaming, and chasing. The world has changed, and so have the zombies of 28 Years Later changed along with it.

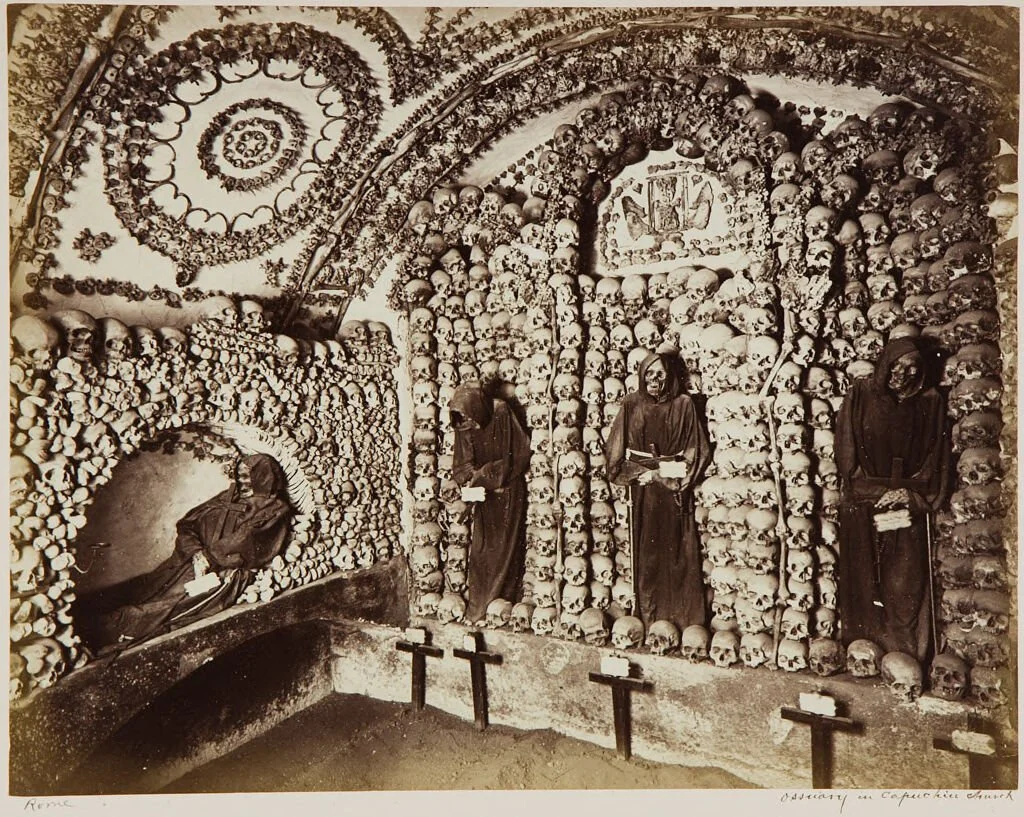

Of all the characters in the film, Ralph Fiennes’s Dr. Kelson is most respectful of the zombies. He names one of the Alphas “Samson” and describes Samson as “living in the area”. Dr. Kelson keeps himself busy collecting bodies. He uses their remains to construct a great bone temple, reminiscent of ornate medieval ossuaries. The Lindisfarne survivors avoid him. They find this practice grotesque and frightening. They prefer to bury their dead like we usually do now, in lonely little graves on the very edge of the island.

We have not always lived so separately from the dead. For hundreds of years, people would visit the Capuchin monastery in Palermo in order to clothe and tend to the skeletal remains of their family members. At the Fontanelle Cemetery in Naples, people would regularly hang out in the bone-filled caverns to leave gifts and chat with their loved ones. Dr. Kelson’s bone temple is part of a long human history of finding ways to continue our relationship with the dead.

Thus, 28 Years Later links the condition of the zombie, of the dead, and of the world. Death is not an end. It’s a transition.

Boyle and Garland are deeply unconcerned with the typical plot drivers of zombie films. There are no cures or quests for a zombie-free paradise. The movie accepts the changed world. Instead, 28 Years Later asks its protagonist, Spike, the only question that there really is: how do we live? The movie presents Spike with three different options.

He could live like his father (Aaron Taylor Johnson). His father is cut from the same cloth as Rick Grimes in the Walking Dead or Will Smith in I Am Legend. He’s a classically masculine paternal type. He has all the important survival skills and makes the hard choices to physically protect his people in a hostile landscape. He’s also completely unequipped to handle complex feelings, and has no idea what to do with his dying wife or his sensitive son.

Or, Spike could live like Dr. Kelson. Alone with his temple of bones, but fundamentally kind.

Spike could also live like the roving gang of bleach blonde Jimmy Savile enthusiasts he encounters in the last few minutes of film.The Jimmies are not particularly precious about either life or death, taking special satisfaction in mutilation and torture. The effect of their combined theatricality and cruelty is not dissimilar to a Mad Max villain, like Dementus or Toecutter.

Binaries abound in the zombie genre – Alive versus Dead, Before versus After, Us versus Them. But where other films propose answers, Boyle and Garland offer only ambiguity and transition. They reflect human nature back at us in the form of the zombie: both alive and dead, simultaneously creating and destroying, and always, always in motion. The post apocalyptic landscape itself figures as a site of both horrific violence and redemptive potential. So fittingly, Spike’s journey ends in transition as he sets off into the wilderness, in an echo of another Mad Max character - Max himself.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider becoming a patron of Hyperreal Film Journal for as low as $3 a month!

Megan Mayumi is an actor and writer based in Austin. Letterboxd here: https://letterboxd.com/megmayumi/