Atrocity Exhibition: The Continuing Resonances of Peeping Tom

We see first an eye, then a man walking down a dirty London side-street. He has a camera hidden in his jacket, pointed at a working woman. The man, we soon learn, is a murderer. He films the faces of his victims as he kills them, stabbing them to death with a knife cleverly hidden in the leg of his tripod. This is our entrance into Michael Powell’s film Peeping Tom, through an eye, and then, the lens of a camera—an apt opening statement for the “film that said everything there is to say about filmmaking,” as it was described by Martin Scorsese. But what hasn't been said about Peeping Tom? Today the film has been retrospectively given incredible powers of foresight by modern critics. Frequently cited as an “early slasher” or even an “early found footage film.” It is a film whose seemingly endless influence has only swollen with age and reputation.

Peeping Tom is defined by its legacy of disaster and redemption. It was a failure upon its initial theatrical release in 1960, condemned by the British press as obscene and ignored by its public as sickening and immoral. The story of an amateur photographer with a knife, murdering women while filming their expressions of pain and fear was far too grotesque for post-war audiences invested in kitchen sink dramas and escapist comedies. Its “redemption” took part in waves as the film, initially censored across Europe, leaked out to the art-house cinemas of New York City and was passed amongst film school students in black and white transfers of the original print. In 1978 it was given a limited release by Corinth Films, financed by filmmaker Martin Scorscese, and by the late ‘90s it became available on the home media market with a laserdisc release by Criterion. It has since fallen in and out of print on DVD, become a cult cinema staple and part of the film school canon along with Michael Powell’s other works.

As the film rose in prominence and was seen by more and more people throughout the last decades of the 20th century, it was granted a critical reappraisal. Critics were drawn to the fact that Peeping Tom was overtly a film about cinema itself. It is a film which takes seriously the often inscrutable, violent power of images—both their creation and consumption. It is also the work of a filmmaker embittered after wandering in the financial desert of independent film production, taking a proverbial sledgehammer to the industry and the public's carnivorous appetite for images and, what people call today, content. Peeping Tom oozes with Powell’s cynicism about the business of filmmaking and places the act of making images in an extreme and disturbing light.

But what can Peeping Tom still tell us today? Like most works of art rejected in their time there has always been a prescience to the film. Powell’s statement on images and media was relevant when the film came out in the early 1960s and is still incredibly relevant today. There are elements of the film that still read as shockingly contemporary to modern eyes and have resonances to our social media world where the act of looking at a screen in our private time, or taking a video of a stranger, are no longer viewed as strange or anti-social, but are instead commonplace behaviors. We are bombarded by images of death to the point they are trivialized, and the decision to take out a camera and shoot a video is arbitrary. Scopophilia, the pleasure of looking without consent, explains not only the mind of our killer in this film, or of filmmaking in an allegorical sense, but can be seen today as to indict behaviors which have come to characterize our entire society. In this way Peeping Tom, and the murderous character of Mark, gives us a way to think about the violence of a society which is more than ever obsessed with the images, screens, and media it surrounds itself with.

So let’s bring the focus in tighter on this character. Our titular “peeping tom” is a man named Mark Lewis, a focus puller for a film studio and part-time pornographer for a local newsagent. He lives in the attic of his childhood home surrounded by his cameras; having converted the room into a private cinema where he develops and screens his collection of snuff films. He is a quiet and strange man, regarded by those around him as simply “that bloke.” In an early scene, we see him peek into the front window of his downstairs neighbors apartment as they celebrate a birthday party. They, like most others in the film, regard Mark with a kind of curious bemusement, the way one might treat an overly formal child. He keeps minimal conversation with his coworkers and neighbors, and responds to the coy, probing questions of the nude models he photographs with vague answers as to his personal life.

It is in the character of Mark that Peeping Tom distinguishes itself from a typical crime thriller or the more contemporary slasher films it is often thought to inspire. There is hardly enough investigation in the film to make it count as a detective story, and in the slasher films of the ‘80s, the killer is a blank slate marching toward their victims. Peeping Tom, on the other hand, relegates its investigators to a C-plot and makes Mark the driving instigator of the story. We inhabit Mark’s point-of-view throughout the film, not that of the detectives looking to catch him nor that of his female victims. The killer's psychological profile is not a mystery either. In fact, it is practically laid out for the audience in the first act of the film. In an early scene, Mark shows his downstairs neighbor, a woman in her early 20s named Helen, a sequence of films shot by his scientist father. In this film we see Mark as a child, a flashlight shined in his face as he sleeps, lizards thrown onto his bed in the middle of the night, all in front of the camera. There is even a shot of Mark approaching his mothers dead body, still laid out on her deathbed. Mark, we learn, was the primary subject of his fathers research into “expressions of fear in children.” The sequence ends with a shot of Mark’s father, entering the frame out of focus, to give Mark his birthday present: a camera.

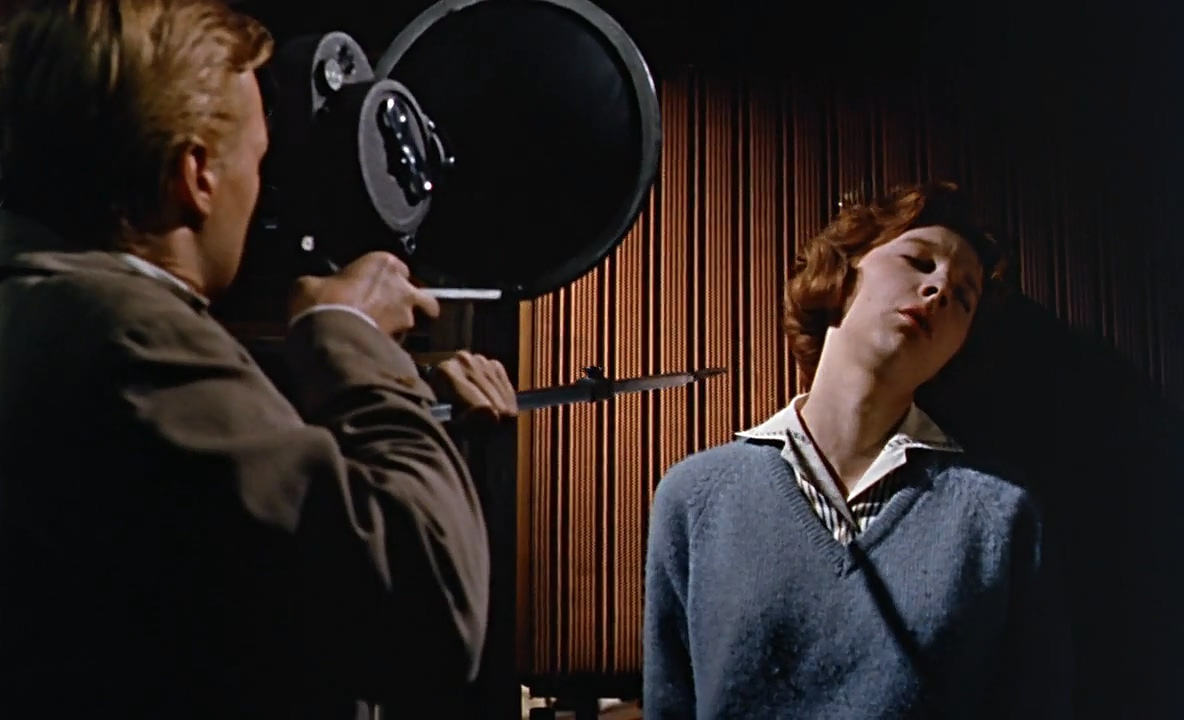

For Mark, capturing the fear in his victims' faces is a scientific enterprise, dutifully carrying on his father’s studies. The psychological motivations for Mark’s crimes are not saved until the end of the film as a kind of missing piece of the puzzle, but instead are given to us early on and frame Mark’s actions as an outcome of a life lived as an experiment in front of a camera lens. There is a tragedy to Mark’s obsessive pathology which makes him understandable and even, perhaps, relatable to the audience. It is worth paying attention to how actor Karlheinz “Carl” Boehm portrays Mark’s relationship to his camera. He holds and pets it with a practiced, neurotic sensuality, treating it as if it were an extension of himself and as an object with an agency of its own. This is implied by his humanizing language towards it; he often describes the camera as being the one who wants to film. As theorist Catherine Zimmer writes, the critical reappraisal of the film focused primarily on the psychosexual angle of Mark’s motivations, leaving the role of the technology he uses under-explored. Zimmer remarks that Mark’s murders are made possible by the revolutions made to small gauge cameras and personal photography equipment that emerged in the mid-20th century following the Second World War. The new designs trickled down to the consumer market after finding use with the armed forces. As image making technology changed and became more diverted towards the multiplication of smaller and cheaper mass consumer products, Mark’s murderous pet project, his “documentary” he calls it, was made possible.

This is an important point to keep in mind because Peeping Tom is not a film about a particular moment in film or filmmaking history, but is about how the possibilities granted by our technology make way for new and increasingly distorted relationships with the world around us. There is something quaint about Mark’s private murder cinema from our modern sensibilities, but what still rings true is his self-isolation, obsessive viewing and reviewing, and antisocial affect. It might even remind us of a relatable figure in the digital landscape, the shut-in internet addict. It is easier now than ever before to cocoon ourselves inside private shells of visual enjoyment and be surrounded with images of sex and violence, even if we aren’t looking for it.

There is also something to be said of Mark’s constant surveillance of others. We learn towards the end of the film, after Helen discovers his crimes, that his father had long ago wired the house for sound as part of his experiments. We see her horror as Mark plays back recordings of herself and her mother, the sounds of her own laughter. Mark is an observer whose experience of the world is granted to him primarily through his apparatuses—his camera, his hidden microphones. What they capture is what structures his psychic world. He only seems to truly experience what he can see and capture through the lens of a camera. In this sense we are not so different from Mark. We, like him, are surveillance officers living in our control rooms, as our technology comes to fully mediate and eclipse our felt experience of the world around us.

Perhaps we can start here, that Peeping Tom is not a “proto-slasher” or “proto-found footage” film at all, but is in fact a throwback to an older style of horror, the monster movie. Placing the film in this lineage suggests something more in line with Powell’s previous work as a filmmaker always insistent on leaning into elements of the fantastic and gothic. Monsters, of course, are not born; they are created. Mark is a creation of his father’s experiments, of his father’s obsessive desire to capture expressions of fear and horror. Mark, much like Frankenstein’s monster, is a tragic unfinished experiment attempting, through the only way he knows how, to form some connection to a society he feels alienated from. Released in 1961, six months before Hitchcock’s film Psycho would be released, in the decades after the war, the old cinematic monsters no longer spoke to the situation of a world where images of carnage and human suffering from the war were widely screened. Powell’s vision was one that was too forward-thinking and yet close to home. Mark Lewis is a monster of his times which continues to haunt us still today.

Daniel Pemberton is a writer and musician living in Brooklyn, NY. He holds a masters degree in Media Studies from The New School and plays drums for a punk band called Pamphlets. You can find him hanging out at your local used book shop or on Twitter @danielpemb.