Our Good Pal, Jomo

I own two posters for the film Thomasine and Bushrod—one large, one small—each because I couldn’t bear to part with the other. One, a promised gift for a friend, now represents the disappointing promises of friendship I made:

“I have something for you.”

“I’ll give it to you one day.”

“…this will just be our thing…”

Always a “next time,” “some time,” but never “any time.” That would be too much effort, too great an inconvenience. So, this gift of a poster sits next to “my poster” for the film, each dueling it out for the chance to be unrolled and framed. I doubt a victory in either case.

Rolled, they sit side-by-side in an unlabeled box, somewhere in my apartment, filled with unopened boxes from a protracted move—two years to be exact. Why should I bother? I’m moving—again—soon. Each box contains a number of posters, books, delicate ephemera—all memories of things I have watched, or hope to watch. Some day, tomorrow, maybe…

I wonder where exactly these two posters sit in my apartment, so I can look at them. It doesn’t matter. I have a photo on my phone, but I don’t need it. I can recall it from memory:

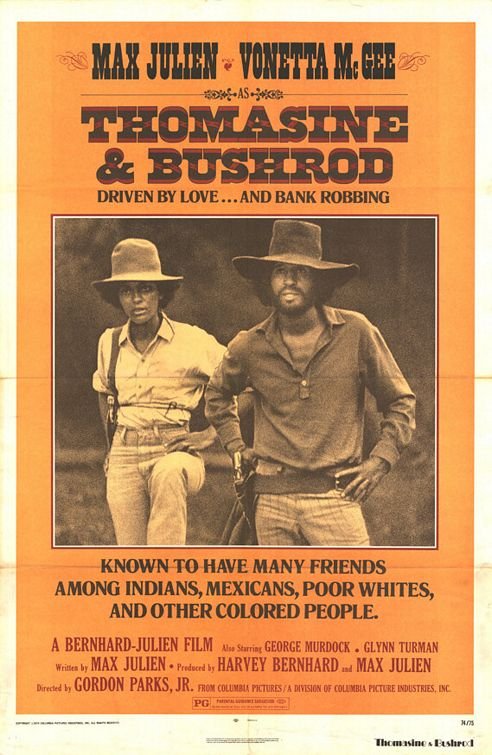

THOMASINE & BUSHROD

KNOWN TO HAVE MANY FRIENDS AMONG INDIANS, MEXICANS, POOR WHITES, AND OTHER COLORED PEOPLE.

Between the title and tagline sits a striking promotional shot of Vonetta McGee and Max Julian’s titular twosome. Stars, they gaze out into the distance, unbothered and effortlessly cool.

Among their friends is supporting actor Glynn Turman in the role of Jomo. Missing from the poster, his face is cast onto my mind like Jesus in velvet. His smile trapped like joy in alabaster—indelible, impossible, forever.

You see, Thomasine and Bushrod doesn’t truly start until their friend enters the frame. From another picture, or rather, another planet, you first wonder how he made his way onto the set, but like any good friend, he wins you over with his charm, and that special quality possessed by every good character: charisma.

Soon after their first encounter out somewhere on the road, the trio form a short-lived troupe, a la The Barrow Gang, predicated on an outsider's bond, an understanding of the world as a thing black and white, rich and poor. From this point, it should be clear—Thomasine and Bushrod will lead to the same end as its well known inspiration, the story of Bonnie and Clyde.

One of the great doomed love affairs—their names are sung as one by Serge Gainsbourg and Brigitte Bardot, themselves a legendary, if not brief, yet potent force in pop culture. Heloise and Abelard, Romeo and Juliet, Bonnie and Clyde—from their headline-driving crime spree, and its 1967 Warren Beatty/Faye Dunaway immortalization, it’s not hard to see why the pair are remembered. It seems they were the only ones having any fun during the Great Depression. How nice it must have been to be the nation’s Zoloft. When all were hungry, the pair promised something tastier than a slice of bread: thrills. But what if Serge and B.B. sang of Buck and Blanche, W.D and Henry, Raymond and Joe or Ralph, poor Ralph, in the same breath as Bonnie and Clyde? What if? Or rather, what is the story of Bonnie and Clyde if not a romantic paean to danger, to sex, to love. Who knows? But anyone will tell you Bonnie and Clyde, et all just doesn’t have the same ring to it. And sadly, neither does Thomasine, Bushrod, and our pal, Jomo. Maybe the papers knew what they were doing when they picked Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow as the faces of danger, of rebellion. More than good shorthand, it was brilliant marketing.

With his comical Caribbean accent, Turman’s Jomo promises antic energy on arrival and delivers until his end. A loyal fool, an impish lackey, he follows the pair until his redeeming, sacrificial turn. He too gives all for love. The least he could get is a poster mention.

Juniper Lessno is a movie buff living in Asti, Italy. Her favorite films involve disaffected teenagers, gonzo energy, and moody atmospheric scores. Find her online by searching old Wikipedia edit histories of your favorite movies