Mother of God! Nunsploitation at the movies

“They think the whole thing is about rapture.

But no, friends, no! What the Beloved wants from us is action. What he wants is that if one of your friends is sick, you take care of her.” – St. Teresa of Ávila

“Get more out of life. See a fucked up movie.” – John Waters

Surveying the visual landscape of our cloistered lives since covid’s intervention in early 2020, I can’t take my eyes off what feels like an omnipresent and increasingly relevant figure (anachronistic as she seems): the nun.

Look around! From the vinyl habits of J. Lo’s backup dancers in Marry Me (2022) to Paul Verhoeven’s sacrilegious sendup Benedetta (2021), Charli XCX’s “Used to Know Me” music video and the ever popular ineedgodineverymomentofmylife meme account. If you’re looking at a screen, you’ve probably come across a religious sister.

We’ve seen 2020’s Black Narcissus miniseries adaptation; Rebel Hearts, the 2021 documentary about the feminist work of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary; Corrine Halbert’s Acid Nun comics; 2021’s minor Hulu-streamer Agnes; and the CW-core 2022 PG-13 female exorcist exercise Prey for the Devil.

Even The Batman (2022) opened with “Ave Maria” and fucking nuns — as distinct from nuns fucking, but I promise we’ll get to that.

What the hell’s going on?

The first years of the pandemic have emphasized our interdependence and our precarity. Involuntary isolation, the humdrum of domestic tasks, quarantined sexual frustration, personal responsibility that feels hopeless against institutional violence and neglect, and a deepening desire for transcendence.

We’ve become nuns.

I admit this could all be the work of my apostatic algorithm, combined with the reality that the nun has never really left the popular cinematic imagination – she’s too burdened with meaning and as an oxymoronic visual object. But I’ve begun to feel a little more avowedly sisterly too, even though embattled religiosity is something I wanted to leave behind with indoor dining.

I knew where to turn: There was a subgenre I’d been meaning to explore, one I stumbled upon in the hallowed aisles of I Luv Video, nestled in between the frankly nastier sounding nazisploitation and women in prison DVDs. Nunsploitation?

If your first thought is taboo-breaking lesbian orgies, breasts bared and then beaten, culminating in some calamitous confession or exile – yeah, you've got the gist. The plots are as dependable as a Rosary (and any deviations from the norm usually disqualify them to me as genre fare, like the vampirism of Alucarda or the uncloistered protagonist of Ms. 45). But there’s wide worlds contained within. For the uninitiated, you might be surprised at the range of production values – from the sub-Monty Pythonian to awe-inspiringly majestic that compares with non-sploitation like Rivette’s La religieuse or the masterful I, the Worst of All.

The nunsploitation movie is not just an erotic novelty, but an often sorrowful mystery, an entry in filmic tradition that is playful and tragic, as revolutionary as it is retrograde, salacious and miraculous. Just what I needed! Under the weight of isolation, there was something promising about the prayerful possibilities presented in solitude, especially in sleaze, which feels truer to life than the sacramental rigidity of the Church.

As the pandemic has been cause for mass self-reckoning and spiritual awakening, there has been an increase of state and terrorist attacks on bodily autonomy (feeling all the more pronounced here in Texas). Since 2020, abortion rights have been stripped away. Compensating sex workers has been further criminalized into a felony offense. Access to health care and even public life for transgender people is endangered or illegal. These awful displays of power are often given voice and moral authority by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

To love this genre requires at least some aesthetic attachment to an oppressive imperial force that promises salvation only at the cost of earthly delights and basic human dignity. But it’s somehow harder for me, now more than ever, not to feel cut from the same cloth as these brides of Christ. In their powerlessness, I recognize my own. Maybe it’d be better to sever ties entirely with the visual pleasure of the Church’s iconography than to look for comfort or connection within its confines. But if the Church gets off on withholding, then nunsploitation at least gives up the game.

Pleasure for these women is something only snatched from the clutches of the paternal tyranny that revels in it. Look behind convent walls and through the vows, and you’ll find a collective of lesbian female friends. A space that forges the separation of church and self-states, if you will. Utopian, transitional, transformative – except for the apparatus that occasions its very existence. The sisters have no choice but to weather this structure, to create something to believe in, to find pleasure (and spirituality) within powerlessness. And these movies almost universally reveal a vertical power structure where God is not at the top, but instead the hypocrisy of the Vatican.

Of course, the generic revelation of patriarchal abuse within the Church is far from revelatory. And whatever transgressive stance nunsploitation presents is maybe undercut by its grueling portrayals of torture, sexual violence, and death. These are flagrant cash-grabs, produced en masse by filmmakers worldwide in the wake of Ken Russell’s 1971 scandalous success The Devils, satisfying a niche (presumably straight male) audience with sadomasochistic softcore, often “based on” the real-life tragedies of unwilling novitiates. We are in the cheap and reactive space of exploitation cinema, where revolutionary readings contend with the conservative or opportunistic impulses of the filmmaker (and his [sic] audience).

Nunsploitation often plays it straight when depicting hierarchical abuse. Or raises the violence to an absurdist pitch, as in Norifumi Suzuki’s School of the Holy Beast (1974). Or cheapens it into redemptive suffering, as a road to salvation and back into the Church’s good graces, as in Gilberto Martínez Solares’ 1975 production Satánico pandemonium. These stories are sometimes presented more like farce than tragedy. But I find more often than not, the exploitative nature of the genre means that the torment isn’t glossed over or romanticized, but centered and recentered in a way that lends these movies a materialist feminist edge.

Still, depending on where you’re standing, watching nunsploitation as proper narrative cinema and not pornography might require a vow of charity: I will read against the grain, with generosity. Their fleshy, violent preoccupations make some productions difficult or triggering to watch with genuine investment, rather than a perspective of irony or sexual desire (in a register of defense or perversion). No shame in just getting your rocks off, but I believe if you can find grace in this sleaze, you can move mountains.

That’s movie magic!

With every passing movie, I found another connection beyond shared isolation. It seemed the life of a nun wasn’t dissimilar from inhabiting a trans identity: fetishized and seemingly at the mercy of the powers that be, often wishing simply for joy or deliverance, either obscured from view or subject to scrutiny. The devotion, survival, and rebellion of these lonely souls – and my own tenuous history with Catholicism – had made the onscreen convent a potent (and convenient) site of spiritual disidentification these past few years.

Identification with the protagonists on screen is coincidental with the objectification of a subjugated, hidden, or transgressive body. Inasmuch as the religious sisters are doubly constructed as women and then as nuns, the process of placing yourself in their sandals is affective forced feminization, and/or conscription into sapphic (be)longing. The convent provided a surrogate community while it was impossible to leave your apartment.

Marketed for straight men, nunsploitation is one of the few genres with consistently women-majority casts. Often there’s not a man in sight, except as overt intrusion or sexual object himself, and the camera’s voyeuristic gaze reduces the Holy See to a peeping Tom. To watch is to assume the position of torturer or victim, confessor or accused – and few of these movies ask you to disavow your humanity as such. We are the nuns, remember? In this way, the viewer’s awareness becomes fluid and sympathetic: if in exploitation the cruelty is the point, then nunsploitation wields it with exactitude to emphasize the bonds between its heroines, the shared humanity between viewer and onscreen subject. Maybe that’s why more often than not, this genre reads to me as thorny, rather than horny. Or maybe I’m just repressed.

I think I’m optimistic. Engaging with these stories of spirituality in the face of religious oppression, there emerges the forlorn hope that I might somehow coax a sympathetic embodiment out of the subgenre’s images. Or successfully petition the nuns for reciprocal devotion myself. Are their spiritual ecstasies so impossible? Are they always doomed?

In the face of constantly renewed or heightened powerlessness, it makes sense we rely more deeply on coping mechanisms: spirituality that enables a more present embodiment, or else something distracting and disassociative. The best movies, or my favorites, mesh these into a singular device, an empathy machine. Nunsploitation deals explicitly in this generative friction between spirit and body, in the most hopeless of conditions (when the narrative arc almost always bends toward torture).

What do the nuns make possible? Sensuality despite or truly because of the incoming Inquisition. Solidarity under the watchful eye of those holier than thou. Subterfuge, behind every closed door or boldfaced, transacted with a smile. Spirituality – in the humbling lack of satisfaction, that there is a reverberating worthiness to being alive and helping others stay alive.

Once shock itself is devalued, you have to look for meaning in what’s left.

Resist the desensitization that comes from hyperarousal and come face to face with every person’s inherent dignity, when it feels impossible to feel, or to be seen, or even allowed. We’ve made it this far. As one beleaguered soul insists in Story of a Cloistered Nun, “You are brave, sister!”

With the conventcentric horrors Consecration and The Nun 2 on their way to the big screen, it’s time for some prayerful contemplation. May the following list of film texts provide an opportunity for you to explore the sacred heart of the genre’s bloody excess before you consume any watered-down (but probably still fun) studiofare later this year.

Let us pray.

Story of a Cloistered Nun (1973) dir. Domenico Paolello

A serious and beautiful production, where reflections in gilded surfaces distort a painful reality. Story of a Cloistered Nun makes for a maybe unfairly impressive, if narratively typical, entrypoint to the genre. Overshadowed by Paolella’s other 1973 nunsploitation pic The Nun and The Devil (starring Anne Heywood of The Lady of Monza), this near-masterpiece presents the harrowing and triumphant trials of a novitiate interred by her family for loving beneath her station. Her mere presence seems to reduce the rule of the Church into its purest calling: care.

The Demons (1973) dir. Jesús Franco

Misunderstood sleaze auteur-gynophile Jess Franco’s The Devils ripoff tells its own compelling Sadean story about a pair of literal sisters and their navigation of an especially sadistic inquisition. This includes some spins on genre conventions, including a couple that seems to come for you, the non-captive audience. For non-Francophiles, prepare yourself for more zooms than you knew were possible and ill-fittingly groovy soundtracking.

Flavia the Heretic (1974) dir. Gianfranco Mingozzi

A historical epic in which militant Flavia becomes the anti-Joan as she wages open rebellion against the Church. Her reverse conquest is corrupted by patriarchal imagination, limiting her revolutionary action to power grabs and perpetual violence. An utterly sad movie where spiritual presence is only attained at the peak of pain, which is something like scripture for this subgenre. Nevertheless, this is one of a kind!

The Castro’s Abbess (1974) dir. Armando Crispino

The dramatic tale of a righteous nun whose pregnancy brings the wrath of the Church upon her. Centered around a haunted, spectacular performance from Barbara Bouchet, this freaky film is complex as it is carnal, and one of the better explorations of convent power dynamics. A doomed story in which the inquisition perverts romantic love into a deadlocked freefall toward the abyss.

Sister Emanuelle (1977) dir. Giuseppe Vari

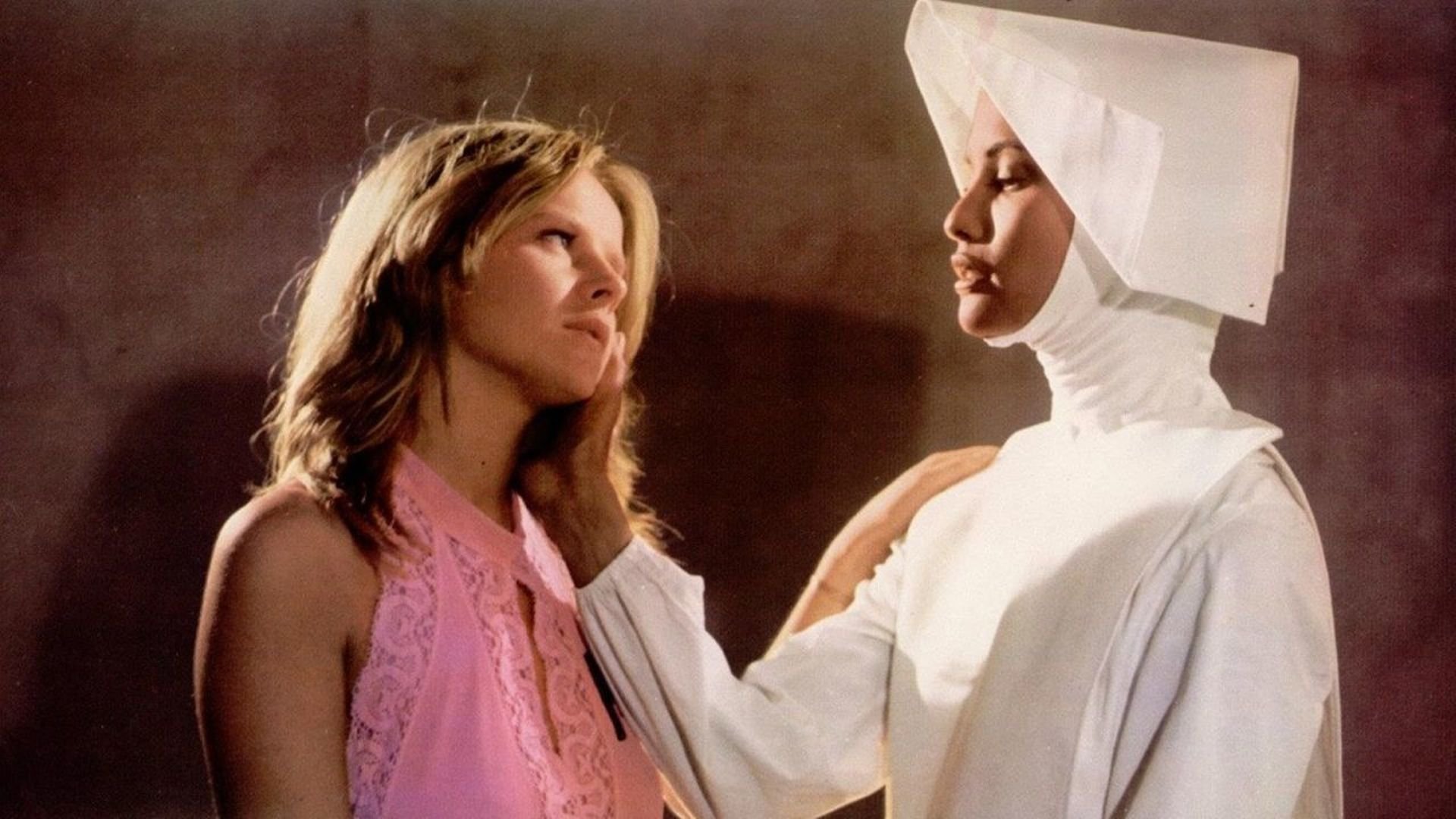

Um, I like it tha best when nuns r nice to each other. Much less a convent-drama nunsploitation movie than an Emanuelle movie, but the flagrant rebuke of religious piousness transfigures its softcore soapiness into a fantasy of emancipation that enters it squarely into the canon. A pure rejection of Church cruelty, shame, and punishment! Emanuelle is the rare joyful woman who moves through the nunsploitation, a beautiful dreamer. Her disrobing spells movie magic, not certain death.

Behind Convent Walls (1978) dir. Walerian Borowczyk

Behind convent walls, softcore is unsimulated. If you know Borowczyk, you might be surprised how carefree this is. This is pure ecstatic vision, freaky and fun, handheld and naturally lit (shot by the great Luciano Tovoli). The movie opens a doorway to constant insurrection, barely and unnaturally contained: the tension between God as eternal sensual presence and patriarchal control. There are always men, there is always His wound, and there is always the possibility opened up by play – that a vial of holy water can be drawn even from the sea of shame. Watching a perfect movie as the mirror to a flame, we become the ray of light between them.

Images in a Convent (1978) dir. Joe D’Amato

Major work of nunsploitation here! A movie that plies at the difference between the church of God and the church of the world, the evil of man and the evil of Satan. These distinctions make little difference in the lived experience of the convent nuns, whose subjectivity is communicated here almost entirely as sexuality. Images' hardcore representation of their inner lives petitions the difference between gender and sexuality a la Andrea Long Chu's subversive application of Catherine MacKinnon, a reduction that can maybe be more easily exploited than explained. Or maybe I'm looking for holy water in a pool of sweat. Either way: It’s a reflective surface.

Note: Features maybe my favorite score ever, an omnipresent organ drone that reaches an increasing fever pitch.

The Other Hell (1981) dir. Bruno Mattei

About as close as nunsploitation gets to a house of horror. POV: In the name of the most Holy Trinity, you’re possessed by the Devil and your godloving sisters are praying over you. The sun is shining. The Devil is a tortie. As the innermost reaches of your soul are overtaken by fiendish pranks and nightmares, do not forget that even the attic and evil laboratories must be blessed to rid your convent of demons!

Damned If You Don’t (1987) dir. Su Friedrich

Okay, let’s be honest: This is a stretch as nunsploitation, but I implore you to watch this black and white masterpiece that tackles all the requisite generic themes with skill and wisdom. There's a good nun, a bad nun, and a woman getting wine-drunk watching Black Narcissus on the mattress on her floor. There’s the other woman, reading about Benedetta Carlini from the perspective of Bartolomea Crivelli, remembering the nuns at school, going to the aquarium, singing hymns. Remembering the loud city song, Patti Smith, in immodest acts, acts of faith, all of it: God.

Dark Waters (1993) dir. Mariano Baino

The only feature film by a would-be heir to Italian horror legends, this dark and stormy nun saga is a God dream. This is everything, like the water covers the sea: A slow-burning apocalyptic vision of conspiracies and monsters of the deep that call to the sister’s own depths (and I’m speaking mystically, not euphemistically). One of the genre’s most moving and humane offerings. This is everything.

Exploitation films do not have a reputation as empathetic, but instead for dehumanization. While nunsploitation is at first hard not to understand purely as taboo-breaking smut – and it is that, of course – its best titles are a profound study in the emergence of grace from bare life, comradery in the face of oppression, and erotics as self-reclamation.

Encountering a dark night of the soul, may you find beckoning reflections in these unfortunate onscreen sisters, whose lives might feel downright relatable. In their suffering, you won’t find commiseration or subversion or (God forbid) redemption, but maybe somewhere to look for a human response to impossible situations – righteous anger, conspiracy, revenge, surrender, love, or the call to help those around you.

Peace be with you!

Patty Nice is a writer, artist, and educator living in Austin. She makes comics, rides bikes, and doesn’t know the first thing about movies.

Follow her on Letterboxd.