The Filmist: Equilizer 3 & 2001: A Space Odyssey

The Equalizer 3 – Antoine Fuqua

As of last month, I’m one year older now than I was—which is “not actually old, but old enough that I feel old and call myself old constantly.” More grey hair than I thought, less energy than I should have. For my birthday, after sushi and sake, my family and I caught an evening show of The Equalizer 3, purely out of chance, where Denzel Washington seems to be going through the same thing. There were more ambitious things playing in other theaters, and even in the same theater, but there were four of us, and we needed something that would do the job for everyone— something generally pretty easy, and fun. For the most part, The Equalizer 3 accomplishes those minor aims.

Much like the other two films in the series, The Equalizer 3 is pure pulp, with no room for any real narrative or moral complications or prolonged moments of introspection. What is different, here, as has been remarked by other reviewers since it’s release, is that it’s a harsher film in it’s depiction of violence—where the first two films seem to relish the moments where Robert just fucks some people all the way up with metronomic skill while avoiding anything too gruesome, the first five minutes of this film makes you very aware that it has altogether different aims: a gun gets shoved through a guy’s face; a guy’s face is split in two with a meat cleaver. Splashes of Grand Guignol. Robert stalks his prey slowly, like the Grim Reaper—sure, they’re faceless Bad Dudes, but this guy is a monster. It almost seems like he would kill a child.

In its way, that’s a lot more interesting to me than the John Wick films, which this series has always been a smaller scale, rainy-day counterpart for—John Wick is just completely invincible, murders a hundred thousand people, grunts out a few lines and gets tossed around like Harold Lloyd in a fantastical world defined by it’s alternate reality dynamics. Yet, we don’t go to the John Wick films for anything intellectually ambitious—we go to it because they’re old-fashioned Stunt Films, like Lloyd, or Keaton. The medium is the message.

Similarly, with these films, the central attraction is watching Denzel Washington be clever, amiable and kick a lot of ass—and, it does do that. There are wrinkles in his performance here that are definitely interesting, among the requisite moments of Washington Charm: his shambling, playful gait as he goes to relentlessly murder another group of people; the way he stumbles over his words and sounds like a real person even in the middle of a climactic confrontation. For the most part, the rest of the film remains in the same zippy, workmanlike tone as the other two, with the caveat that it’s a self-conscious finale for Robert—so, our narrative structure becomes a very well-worn riff on Shane, with Robert acting as an aging protector for the humble people he’s come to love. He’s still clever, and charming, and no one really gives it a second thought that he really seems to enjoy murdering people. But, those sequences of violence do give one pause, and if we were being generous, we’d say they resonated throughout the rest of the film, making those moments where Denzel flashes a wink with the waitress or eats dinner with his new friend and rescuer all that much more menacing. Of course, he’s returning to violence for them—but, is he?

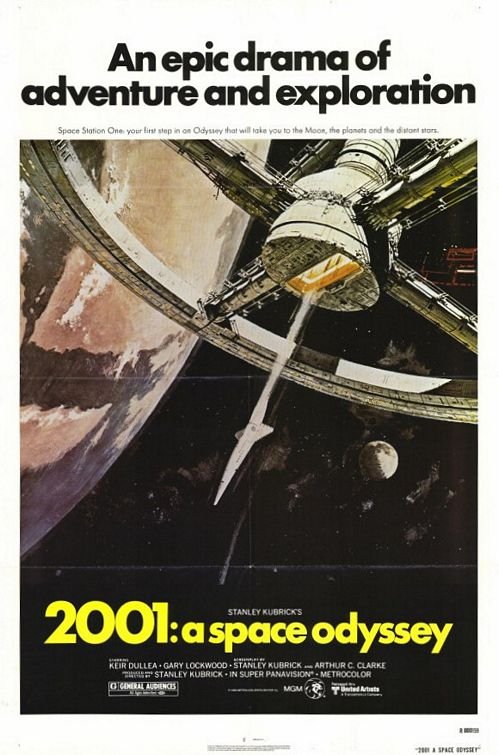

2001: A Space Odyssey - Stanley Kubrick

I’ve got a long relationship with 2001. Who hasn’t, right? I mean, it’s 2001. I’ve seen it many times, and twice before in theaters, and once I actually helped ferry a 70mm print of it down 6th Street to the Alamo Ritz with a projectionist friend from Dallas for one of those screenings.

I won’t waste too much time going over the things I know that you know about the film, and that other writers have already elaborated on, except to say that it’s one of the most forward-thinking science fiction films ever made—narratively, it’s a work of structural brilliance, with a God’s Eye view of humanity’s progress, shot through with Campbellian undertones and with the air of a true Mythic Epic. If you haven’t seen it before it may at first catch you off-guard, especially if you come from the Save The Cat school of screenwriting, the way the field seems separated into three distinct parts, each with their own intellectual aim—but as the film reaches it’s finale, the overarching goal becomes clear. Or, at least for me. Any reading of this film will ultimately be subjective, as was the stated intention by Kubrick, and appropriately, the film is intended not just as a speculative work, but a symbolic one. For me, the secret lies in how much the film does take from Joseph Campbell (and, on writer Alan Clarke’s part, from Olaf Stapledon)—and, by the end, it isn’t just Dave but all of humanity who returns, or will eventually, as Master of Two Worlds.

What I really want to talk about, here, is the experience of seeing 2001 in a theater. I used the phrase “the medium is the message” in my Equalizer 3 review above, and that quote comes from Kubrick talking about this film—it’s designed from the inside-out as a work of Pure Cinema, of brilliant visual storytelling, working on a subconscious, Jungian level, even on a scope as wide as the universe, composed in a series of sweeping musical movements. Every frame is a study in widescreen composition, color theory and emotion through motion, or lack thereof—far from being the cold, robotic filmmaker Kubrick is commonly portrayed as, emotion surges through 2001: awe, wonder and sheer, existential terror. Every edit, an Eisensteinian juxtaposition—an entire book could be written on the death of the three unnamed crew-members alone, done entirely through still shots, monitor displays and sound design.

And, the sound. My god. From the first few frames of darkness, as Robert Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra” booms into full majesty over the image of the Earth caught in shadow, the sun peeking just slightly over it, the sound design of the film engulfs you—which, in the opening Dawn of Man passages, can be more than slightly overwhelming in a relatively small auditorium, made up primarily of loud, loud shrieking monkey sounds: but then, it should be. From there, moments of interstellar revelry set to “Blue Danube,” as Kubrick indulges in rigorously formalist filmmaking in the docking sequences—and, in later passages, cuts all sound, all music save for the most human sound of all: labored breathing, ramping up in anxiety. In his previous films, Kubrick employed dialogue freely, and even voice-over narration in his earliest work, as was commonplace. Here, he whittles away at these until what dialogue there is from the human characters is mundane, even trivial—one more tool, and one rarely used.

This is the film form at its zenith, one that would very rarely be reached again—an all-encompassing film, both visceral and intellectual in equal measure. It commands you, takes hold of you and pulls you headlong down into it.

I guess what I’m trying to say, really, is:

Criterion when?

(Yes, I’m aware of the laserdisc release. I own it. Come on, now.)

Jefferson Baugh The 3rd, or TheFilmist, is a filmmaker and screenwriter by night living in Austin, Texas. He's been an actor, an editor, an AC, a sound mixer and a film critic. He's also a very good tap dancer. Currently, he's shopping his script I CAN (NOT) FORGIVE around to see if anyone will give him some money to make it (please, for the love of god).