The Films of Peter Bogdanovich: America on Celluloid

I’ve been thinking a lot about Peter Bogdanovich movies lately. Part of that is due to me binging a bunch of his work the past few months while stuck at home with nowhere else to go, but the biggest factor is the recent seven-part podcast TCM produced, The Plot Thickens (which comes highly recommended from yours truly). Through interviews with Bogdanovich, the series explores his beginnings in New York through his tumultuous film career to his current day status as an elder statesman of film preservation and advocacy. As I listened to these podcasts every week while working on some mundane report for work in the self-isolation of my apartment, I began to contextualize why I loved his work so much: they are movies distinctly about the concept of America.

There would be no New Hollywood without the likes of Godard and Truffaut, but I think a disproportionately small amount of credit is tossed to the American auteurs those same French cinephiles said inspired them, namely John Ford and Howard Hawks. That’s where Bogdanovich stepped in, synthesizing these very directors’ works and thematic/stylistic quirks, but with a quintessentially post-French New Wave sense of energy and thematic weight. Ford and Hawks are probably the most celebrated directors of Hollywood’s Golden Age, but had radically different approaches to filmmaking and their interests in the stories they put on screen. Whereas Hawks was interested in dissections of secluded subcultures (deserted Wild West towns, small tropical ports, etc.) and the intermingling of characters within these worlds, Ford’s interests were in the mythic, the reconciliation of the American myth and reality and the degree to which both inform our lives today.

Targets (1968)

This is where Bogdanovich’s work finds its pulse, intersecting with these two directors’ own work while also charting his own path. Even in his incredible 1968 debut, Targets, there’s already a clear focus on deconstructing the horrors of the narratives we create for escapism and real ones that lurk just outside our front doors. While having horror titan Boris Karloff on hand was a contract stipulation, Bogdanovich turned lemons into lemonade by having Karloff play an aging horror actor who feels adrift in the tumultuous 1960s. Paralleling his story is that of a mentally unstable Vietnam veteran who goes on a shooting spree. There’s a direct thematic thread within the movie itself, but also an even more interesting one when contextualized within the 50+ years since the movie came out. Within the movie, it’s clearly about things like anti-Vietnam War sentiment, PTSD, and the gradual obsolescence of older movie trends. However, as a movie, it’s oddly prescient about what the American conception of horror is. The halcyon days of Lugosi and Karloff have given way to more “real” explorations of horror (i.e Saw, The Babadook, etc.). In a Ford-esque exploration of myth, Targets asserts that the more fantastical myths that are used to mask the real terrors will eventually crumble and no longer have a place in America. As of 2020, I’d definitely say we’re there.

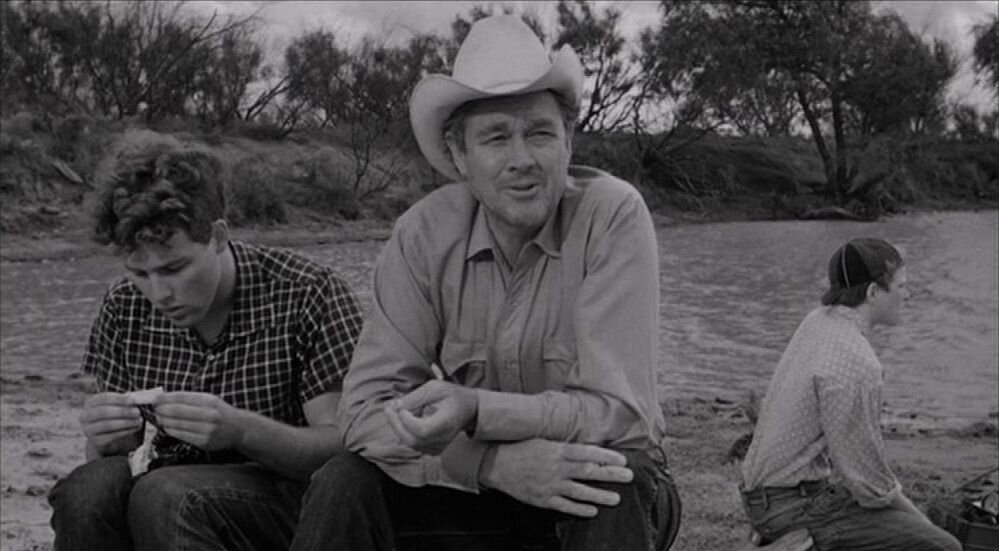

There’s an offhanded remark during one episode of The Plot Thickens that Bogdanovich’s work is about the search of a father figure. There’s certainly a degree of fondness for “paternal figures” in his movies, even though most of these men range from melancholy cowboys past their prime to outright crooks. There’s Sam the Lion in The Last Picture Show, Jack in Saint Jack, and Mos’ in Paper Moon. In the case of the first two, they serve as mentors and leaders to the insular Hawksian communities they live in, the former over a decaying 1950s Texas town and the latter over the vagrants of the Singapore underworld. They desire something more than what they have, but whether through their own lack of trying or inability to face their demons, can’t leave the worlds they inhabit. In true Howard Hawks fashion, they’re reluctant heroes, if we can even call them heroes. Unlike most Hawks movies, there’s not a sense of unabashed joy of these worlds, but rather a sense of despondent acceptance of their failures. Whereas a Hawks world is inhabited by moments of sadness amidst a sea of optimism, Bogdanovich’s worlds invert that dichotomy to have the characters experience fleeting moments of joy amidst their hollow lives. To return to the aforementioned Mos’ from Paper Moon, he contrasts with the previous two men in that he realizes that the world he lives in (Depression-era Midest America) is relentless and cruel so best to take it in stride and get out ahead when he can. He has no delusions of grandeur and finds peace in his con man lifestyle, a life of living moment to moment rather than chasing an ever elusive “better” of the American Dream.

However, Bogdanovich isn’t strictly a cynic of the American dream or culture. Indeed, there’s definitely a sense of optimism that pervades some of his best work, no doubt coinciding with some of the happier moments of his life as he points out. For instance, They All Laughed being made at the start of his relationship with the late Dorothy Stratten and What’s Up Doc? being made at the peak of his love affair with Cybill Shepperd. If anything, these movies reveal Bogdanovich to be a deeply hopeless romantic at his core. Undoubtedly throwbacks to the classic romantic screwball comedies of classic Hollywood, these two movies employ an almost Jaques Demy-esque fixation on near missed connections and a celebration of how love is nothing more than a miracle of running into someone at all. They’re odes to life itself, in spite of all its faults and miseries.

Special mention must be made toward Bogdanovich’s musical choices through his filmography, most notably his frequent usage of distinctly American music, most notably country and oldies hits on many of his soundtracks. The Last Picture Show is obviously defined by its moody ’50s doo-wop and crooner hits, but even more interesting is the use of country music in They All Laughed, a movie that takes place entirely in early ’80s NYC. The juxtaposition of the big city and the rural ballads underscores how removed the narrative is from opulent big city glamor and what a “ground level” story it is, moving from dive bars to roller rinks to dusty office suites, ostensibly giving a big city story a “blue collar” vibe. A telling moment of Bogdanovich’s proclivity toward musical contrast is in Texasville when Duane’s (Jeff Bridges) son changes the radio station almost immediately from a classic country song to a (then) contemporary ’80s pop song. In a movie all about aging and generational passage, it’s representative of how the songs change, but the tune of small-town America stays the same.

It’s that palpable sense of optimism and belief in those moments that feels like the intersection of Hawks and Ford in terms of how Bogdanovich crafts his own vision of cinema. Hawks optimism and celebration of the silver linings of human foible clashing with Ford’s construction or frequent deconstructions of American myth to create something new entirely, a vision of America as a flawed place, but one with its own unique quirks and charms that Bogdanovich is fascinated with. It’s a place he wants to celebrate in his films, warts and all.

Just another guy working in tech in Austin, so he’s probably the worst thing ever. He’s a big fan of surf rock and Larry Cohen movies.