Nico/Garrel: Revolutionary Avant Garde Cinema Lives in 35mm

A new series from Austin Film Society (AFS), “Nico/Garrel: White Light Lays Above,” explores the artistic collaboration between French New Wave outlaw Philippe Garrel and his muse Nico throughout the 1970s. Lovers of rare cinema can thank their lucky stars for AFS, one of the few places on Earth to see these singular avant garde works projected on 35mm celluloid.

Key context for this program is the May 1968 civil unrest in France, during which student-led rebellion against the government grew into a massive leftist general strike. Along with Jean Luc Godard and François Truffaut, Garrel was at the forefront of French New Wave filmmakers seeking to change not only cinema but society itself. Prior to the strikes, in April 1968, Garrel famously said he desired his films to be like a cobblestone hurled into the theater.

Nico, retrospectively regarded as a seminal proto-goth musician, was at the time mainly known for her association with Andy Warhol. Garrel, drawn to her appearance in Warhol’s split-screen epic Chelsea Girls, used her song “The Falconer” in his Boissonnas produced film The Virgin’s Bed. (Further collaboration was briefly delayed by Garrel’s mental breakdown and subsequent electroshock therapy, which inspired The Inner Scar.)

In the wake of the strikes, from 1968-1970, Garrel had remarkable access to resources as a member of the Zanzibar Group, a short-lived cadre of globe-trotting radical filmmakers financed by heiress Sylvina Boissonnas. While the group disbanded before any films were released, the production value afforded to this series’ early works is evident onscreen.

As AFS programmer Jazmyne Moreno noted in her introduction, one can never really know what happens between two artists in a relationship. Only Garrel could tell you what the films are really about, leaving the audience with simply the experience of watching them.

ATHANOR (1972)

This silent short consists of hypnotic long takes following Nico and a woman only credited as “Musky” as a pair of witchy, occasionally nude characters hanging out in a mythical world of caves, palaces, fire and falcons. Athanor is real meditative, zone-out stuff, heightened by the complete absence of a soundtrack, and feels like the cosmic honeymoon phase of the Nico/Garrel collaboration. Appropriately, the title refers to a furnace used in alchemy.

LA CICATRICE INTÉRIEURE (THE INNER SCAR) (1972)

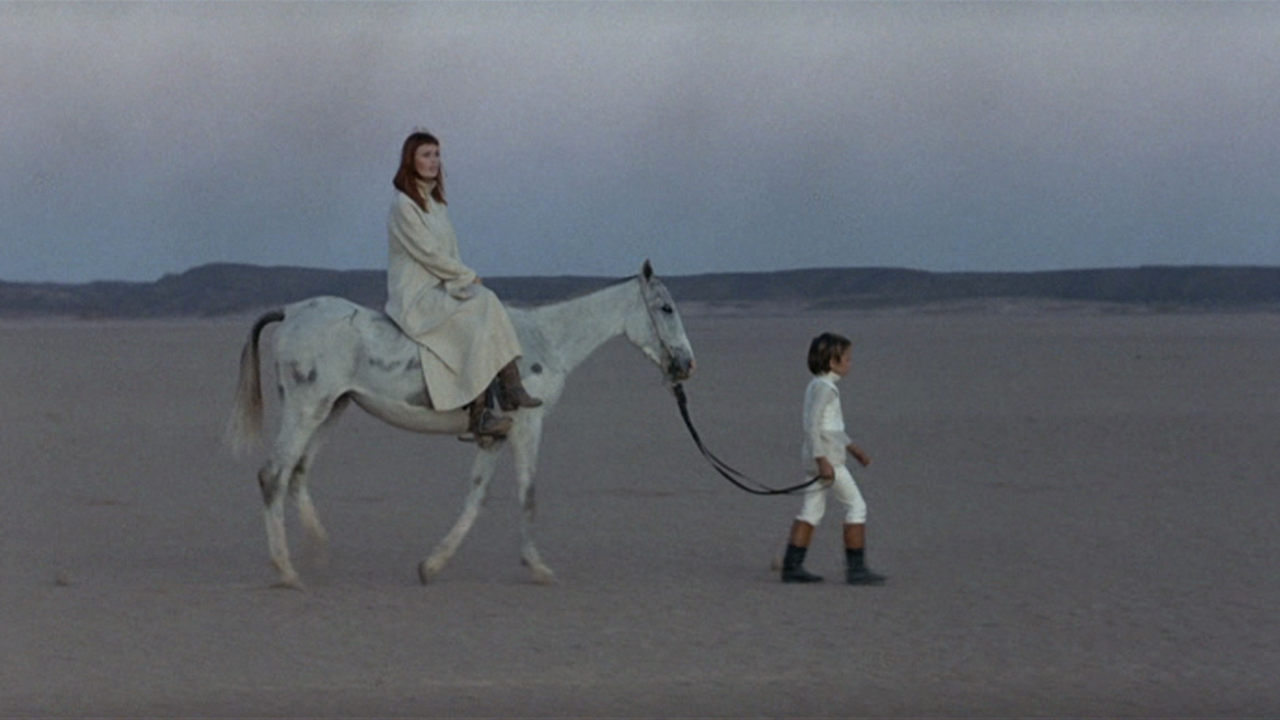

The Inner Scar may represent the ultimate expression of The Zanzibar Group’s mission. The Group’s travel budget allowed access to a variety of trippy primordial landscapes in Egypt, Italy, Death Valley, and Mexico, and enough film and equipment to capture it all at the highest technical level. (Nico used stills from this film as the album art for her 1970 album Desertshore.)

Indeed, watching the intensely, almost embarrassingly personal pas de deux between Garrel and Nico, shot on such an epic scale, feels utterly unique. At one point, Nico implores her silent companion by name, “Philippe, I can’t breathe!” (metaphorically speaking). Later, she calls him the Devil. Garrel’s reputation as a dandy is proven by the frilly shirt-blouse and pant-vest combo he chooses to skulk around the desert in, a self-seriousness approaching self-parody.

While the florid pantomime and Nico’s primal-scream-esque performance threaten to derail the audience’s attention, Garrel triumphs through sheer intensity of vision. The film offers one mesmerising tracking shot after another, punctuated by precisely choreographed stunts and reveals. The introduction of new characters, including a charismatic flock of sheep and a naked archer on horseback, enliven the proceedings considerably.

LE BERCEAU DE CRISTAL (THE CRYSTAL CRADLE) (1976)

Following the epic globetrotting of The Inner Scar, The Crystal Cradle actually feels the more brain-scarred of the two, a eulogy for the failures of the May 68 generation. The Zanzibar Group had disbanded and resources were scarce. The film’s subjects are defeated revolutionaries crashing out by candlelight, becoming insular and hermetic, suffused with romantic melancholy.

Nico’s on-again, off-again relationship with Garrel seemed to have evolved in the same opaque, primordial way, into hushed and desolate minimalism. What action there is consists mainly of Nico smoking clove cigarettes, reading, writing and reciting lugubrious poetry: “I have come to lie with you / I have come to die with you.” When Garrel turns the camera on himself, he broods motionless and blank-eyed, lost in inky chiaroscuro frames for minutes on end.

Behind the camera, Garrel captures fleeting daylit moments with other characters, like flashbacks to another life. But even these are tightly framed and claustrophobic, the opposite of The Inner Scar’s epic wild openness. Garrel’s instruction to the creators of the soundtrack, German psych band Ash Ra Tempel, was for “music to dream to.” Like a dream, the film drags on, feeling longer than its already sparse 72 minutes but lingering in the mind long afterward.

Stay tuned for Part Two of this review, covering Un Ange Passe and I Can No Longer Hear the Guitar.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider becoming a patron of Hyperreal Film Journal for as low as $3 a month!

Matthew K. Seidel is a writer and musician living in Austin since 2004. The above selfie was taken in an otherwise empty screening of Heat at 10:30 in the morning. You can find him on Letterboxd @tropesmoker.