HCAF '24: Interview with Markus Zizenbacher, Director of The Life of Sean DeLear

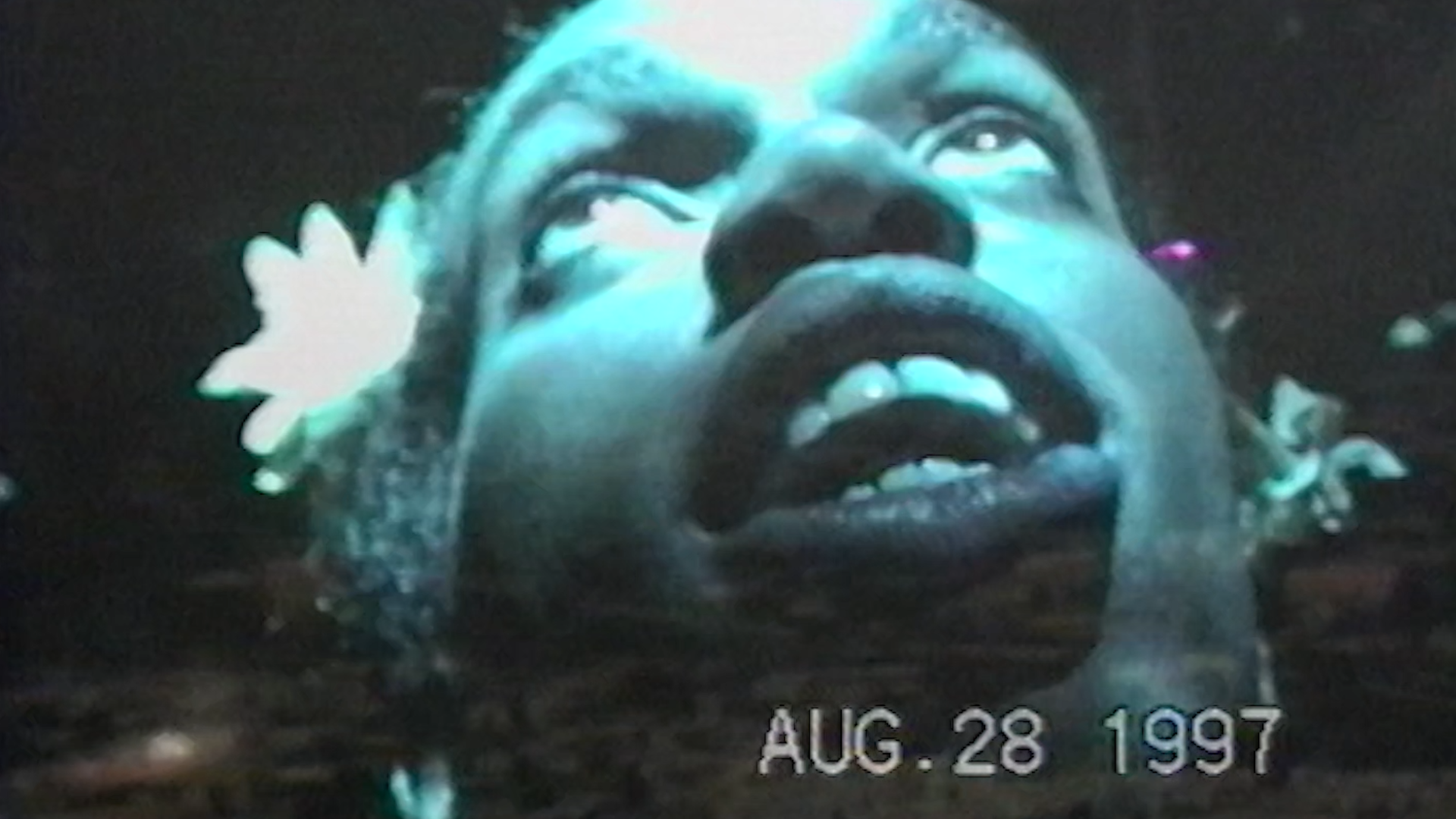

The Life of Sean DeLear, which screened at this year’s Houston Cinema Arts Festival, is a vivacious and colorful look at the crushingly charismatic Sean DeLear and his experiences in the LA punk scene of the 80s and 90s. Markus Zizenbacher is a filmmaker who knew Sean personally. In this article we talk about cinema being a hallway of ghosts, the duty of assembling a life on screen, and living without shame.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I'm joined here by Markus, Director of The Life of Sean DeLear. Thank you for being with me today. I mentioned beforehand that I loved the movie, and I thought it was so eye opening. I kind of believe that cinema, in a lot of ways, works as a Hall of Memory or a Hall of Ghosts. This film in particular, really does feel like that. How do you maintain that sense of reverence throughout the film?

I mean, it's a very good view on the film, because that's exactly what I wanted to achieve. The whole journey started when Sean DeLear passed away in 2017. The film went through several stages. Writing dossiers and getting funds in order to be able to enter this Hall of Ghosts from the past. This was part of the trajectory of the making of the film. I was in a position where I had a friend who kind of accidentally gave me his whole estate to do something with, without even actively saying it, but indirectly. So, I had this responsibility of getting a friend’s vibrating life and my personal relation to Sean DeLear, unlocked via a piece of film. The film started out with putting together the rushes of the archive. Parallel to that there was the project of the diaries by Cesar Padilla and Michael Bullock. They were aiming to publish the diaries, whilst I, at the very beginning, was more focused on the film work of DeLear. So, to see archive material of people that you don't know, it was my journey to identify them and put the ghosts of the past into context. You witness situations unfold in real time that have taken place in a certain time span. You see joy, laughter, debauchery of random people you don´t know, that, without context, can quickly become repetitive and shallow.

My task in the whole project was to get a deeper look into that canvas that was preserved by the archive, and give context to it. It was a big archive, about 100 minutes, not so big actually, but still a large time span of 40 years. For me, it was the aim to make it accessible to a bigger audience. Especially younger generations, Millennials and Gen Zs should be taken on this ride to experience the vibe and lifestyle of our parents’ generation that have lived in a certain way. That was my journey, it was actually identifying the life of the ghosts.

It's so present in the film. I mean, you feel it almost immediately. And I guess a lot of that probably comes from that intro. You mentioned that you were handed this archival footage, which just seems like an overwhelming responsibility. Was there a temptation to make this film entirely archival footage? What was the push that got you to go seek out these talking heads interviews to ground their story in the present as well?

At first, I would say there was the aim to just use the archive. Together with a good friend, Aleksey Lapin, who also made some of the camera work of the film, we were only using the rushes in chronological order starting when Sean was 14. The result was a five hour edit that we screened in 2018 at Sean’s wake in Vienna. We just wanted to celebrate Sean and also see how the raw material worked. So with this edit, I saw the limits of the material that followed a more artistic approach. I mean that version worked as well, but it simply was not as accessible and all-encompassing as I thought Sean’s legacy should be represented.

You have to understand that I had 50 moving boxes in my little room for a long time that Sean DeLear had shipped to Vienna two months prior to his death. I saw them every day and I didn't want to throw them away unnoticed. I started to catalog them and research the bands he was around with, identified people in photos, made some phone interviews and dove into cultural landmarks that influenced him. From there, I wrote a first concept for the film, applied for funds and was lucky enough to get them and could afford to travel to LA where I had Mike Hoffman—who's in the movie and one of the executive producers—open some doors to people who were close to Sean. And little by little I started to get the whole picture of Sean’s life.

Even though I shot around 70 interviews, for a long time I wanted to avoid a talking head documentary, actually, I was really working against it. I wanted the past and present to intermingle and float above time and space. I documented mainly Mike Hoffman, his brother—who is a pastor—and another close friend, Davy Willis. But, then in the course of editing with my co-editor, Sebastian Schreiner, it turned out that this approach was out of focus and I ditched it and started the narration along Sean’s life using the photographs, films, diaries and anecdotes told by his friends and relatives.

Maybe the people still present are stronger than the archive because you can relate to it more, you get more details and can structure it better. The archive is what it is. Of course you can manipulate it (archival footage) in editing as well, but it is what it is. Plus there are only a few scenes in the whole archive that work on their own. Those scenes are in the film.

I wanted to ask what you think this film says about honesty, because Sean was a completely, full frontal, honest person, but there is also a mystique. So what do you think this film says about both the honesty of Sean DeLear and honesty in general?

Well, I would rephrase honesty in a sense that he was rather carefree. Not “not caring” but you know this is this generation. I’m a millennial, so I grew up a little bit on Gen Xer culture. And that was always the picture I had, like you don't care so much about fame and status. At the same time this was a romanticizing view from my side. Because of course Sean cared about who he was and what people saw in him. As Rick Owens states in the film, “the status play is the same in the dirty downtown alley as it is in coke snoring Hollywood hills.” But there’s this vibe that DeLear was more of a trickster personality. Living through the day and not caring about tomorrow. Reinventing yourself every day and every time you drag. One night you're the rocker, punk biker dude, that goes to bars and picks up cops. The next night, you go to some right wing festivity and just provoke with your presence. It's a very situational approach towards life I would say, and he literally lived like this in Vienna as well. We did that. We went to all kinds of spots and had the illusion of reinventing ourselves for one night. Maybe we were just drunk. So, I don't know if honesty fits best, maybe more like directness and the aim for adventure, mostly experienced in various states of mind.

Maybe that is what I mean, more direct, rather than honest.

I mean, the diary is so direct, it is a pure experience drifting from encounter to encounter, then going on from there with his camera that was always present. He had this unsatisfiable drive to go to every party, event, concert, art show etc. and be in the present, at the same time he was a stoner that could not leave the house for days and just watched Perry Mason.

We've talked a lot about the substance of the film, and I want to talk about the technique of the film. I was watching it, and it reminded me a lot of Penelope Spheeris' The Decline of Western Civilization. Was she someone that you look towards as sort of inspiration for how to ground the film, if not her, was there a filmmaker you look towards as like an inspiration for the aesthetic and the style?

Yes, I mean, of course, I love Penelope Spheeris, I wanted to meet her. I know that The Decline of Western Civilization was a very crucial film for DeLear and for this whole generation. That film was played non stop. I think the videotape I have at home was on his VHS player all the time. He kept watching it because he was part of that crowd. It probably kept up his spirits, his energy. So yes, the whole style of filming on location with the people in the film was an inspiration. But, in terms of dealing with archive material, Adam Curtis´ essay films certainly helped me to be more playful and use the form to connect all kinds of peculiar contents. But, in the editing process it quickly becomes very intuitive. For half a year, even more, daily. I was going through the material hundreds of times and was just sculpting and letting the film create itself. Of course there was a lot of reflection, analyzing, test screening too, but it all happened under the spell of creating the ultimate Sean DeLear sculpture.

I think that's probably more reflective of DeLear’s life, that pure expressionism. There's a lot of archival concert footage of DeLear and his band, Glue. Those moments really stood out to me, because you are able to maintain both the energy and the spirituality that comes from being at a concert. Can you talk us through that kind of, that balancing act of maintaining the essentials of a concert?

Well, that's actually easy to answer, because there are only a few Glue concerts in the archive that captured that energy. So, I was actually limited by the archive, there were not so many that were usable. The concert recordings were often of poor quality filming and soundwise, I considered not using most of them. I knew these three concerts had to be in the movie and worked the structure of the film around them. Plus Sean’s singing range was limited. He was around very talented musicians that helped him around that, but it's punk rock. It's not necessarily needed to have a good voice, it's your performance. And Glue created their own world in this very vibrant scene of the 90s.

That punk scene kind of lent itself to unique filmmaking, like the opacity overlays. There’s points in the film where they feel like they're emphasizing the dialogue. What does it mean to you to have these images over images and to use it as a filmmaking tool?

I was so passionate about this. I studied in film school, and it was a more classical way of filmmaking being taught. I was always more on the explorative side. So, this film was a dream, filmmaking wise, because I could do things I would never have dared before. Mixing up diaries, photos, 8mm, VHS, 4K, noK, all these elements allowed me to explore filmmaking from angles and perspectives that were rather obscure to me before.

Methods like layering were a way to create a sort of abstraction that was important to make Sean DeLear accessible on a more poetic level. Having well composed shots like the one of the ocean or the bowling alley with the diary narration, I guess you could easily make the whole film in that manner. But, I was drawn to break every established style in the process. To surprise and work against the expected, give the film some otherworldliness and see inconsistency as part of the formal language.

Something that is maybe a key to Sean's approach to life, he almost died when he was twenty-one, having his neck broken. It was very present his whole life. He had his one shoulder that was a bit thinner, and he always had to trick around it. He actually couldn't really lift his arm. He always had to hold his left arm and support the other elbow, he was disabled in a sense and he was in a lot of pain. That's why he smoked a lot of pot and other substances, as a pain reliever. This existential experience when you're twenty-one and things are close to being over for you, was definitely a catalyst for his ambition to become an artist. At the same time the physical disability and his HIV diagnosis, helped to alternate his world view and be a kind of relativist. He had an attitude towards many topics, but as far as the ending of things go, he was a child of the 70s that “saw it all,” most likely while tripping on LSD. And I really don't know what that everything is. But, he saw it. And everybody around him, everyone who met him and experienced him, was a little bit on that same path. Not taking things too seriously and enjoying the moment. Life can end with [Markus claps his hands] you know, like that. You can go out the door and a car hits you and you're dead. You get a cancer diagnosis or whatever, and it's ending.

I love the ending of the film and how you decide to sort of bookend it with that presentness. Having those readings and having even Sean reacting to readings of his book, what do you think is the influence of Sean today?

Well, I think maybe, the energy that you can get from it (the book and the film) is already something. I mean, fear and anxiety are killers for every kind of personal development. Cutting out fear and anxiety and just going for it was Sean’s leitmotif. Maybe that is worthy of being influential. It sounds so pathetic, but I think that's what his vibe was, that was his whole calling. I think that's, at least it was for me, always something that inspired me a lot during the whole time that I knew him. We (with Aleksey Lapin) did a short film together while he was still alive. We felt like being in a band, just going for it, not thinking too much about where it would lead us. I mean the diary, of course, shows that especially: this 14 year old kid, experiencing all kinds of very interesting and sketchy adventures. It's dangerous and danger is thrilling. So, I don't want to say that his influence is to face every danger that you encounter, but maybe that's exactly it. Danger, spontaneity and a love for people too.

Hello! My name is Eli and I am a film fanatic based out of Houston, Texas. I am currently working on becoming a filmmaker, while also working full time. Film is my hyper fixation turned passion. I simply adore the flicks! I love learning about the history of cinema and seeing how that history shapes what we watch today.

I talk about movies on my Instagram: @notelifischer, TikTok: @loads.of.lemons, and Letterboxd: @Loads_of_Lemons