Humphrey Bogart: Beyond CASABLANCA

Two people, a man and a woman, sit on a couch wearing complicated expressions. The woman rests her head on his shoulder struggling with indecision, a choice between loyalty or her heart. Incapable of committing while under the crushing weight of both possibilities, she asks the man to help relieve the burden, since after all, this decision will also affect him. The responsibility passes onto him like a lightening bolt, one that he is barely able to prevent from wrecking devastation upon his controlled face, but it crackles all the same in his eyes. The woman closes her own eyes for a breath. She is tired. A tragic sort of tired that only heart-rending moments at a crossroad of futures can cause. She is not fully aware of the position she has put the man in. He is far, far away, standing alone in his mind weighing the consequential outcomes of his own choice: to be selfish, or to be selfless. Each of them are momentarily struck silent by their own inner dialogues and from the recesses of their shared memories, violins play variations of the tune, “As Time Goes By”, a tune tinged with the bitter-sweet refrain of all-the-things-that-might-have-been. There are many things that he would like to say to her, so many words that he has been holding dear for too many years, holding them for just this very moment. He does not say the words, however. Instead the words ride hidden in the emotion driving his voice, “Here’s looking at you kid.”

There are few names that resound in the annals of Hollywood history quite like Humphrey Bogart’s and there are few other images that are used as often to depict classic film than those from ‘Casablanca’. If you are going to watch one movie starring Humphrey Bogart, then hands down it should be ‘Casablanca’. Generally agreed upon to be Bogart’s most iconic movie, it has many elements that are still referenced and parodied today. That said, I’m going to leave it there and continue with the next-best five films.

There are a lot of things to enjoy in classic movies- beautiful dresses and cheeky fedoras, charming old technology and automobiles, masterful story craftsmanship, smoldering yet restrained romantic scenes, delightfully pithy turns of phrase- but they also contain elements that are far less palatable. Classic films are, more often than not, rife with misogyny and aggressive behavior toward women, and racist depictions of non-white cultures and people of color (if they were included at all). Film effectively operates as a time capsule, preserving not only the superficial aspects of pop-culture and certain historical perspectives, but also of arrogant ignorance, casual displays of ugly prejudices, and flagrant white supremacy. Toxic tendrils of these same prejudices are still causing great harm today, although they are perhaps more frequently carefully hidden beneath a sinister layer of calculated neutral language. When navigating film history, it is important to actively recognize the things that are not acceptable and to examine our current culture so that we may dismantle all lasting remnants of that prejudice in our present.

So, with that is mind, the following five films (in no particular order) are a good starting point if you are interested in exploring the work of Humphrey Bogart.

The Big Sleep

(1946)

Directed and produced by Howard Hawks, ‘The Big Sleep’ is a noir masterpiece. The dialogue, credited to three writers (one of whom is none other than William Faulkner), is fascinatingly clever and thoroughly quotable. Some of the very first lines are unapologetically flirtatious, immediately catching the audience’s attention. “You aren’t very tall are you?” asks Carmen in lieu of a greeting, to which Philip Marlowe replies, “I try to be.” Howard Hawks’ directing style, being heavily actor-focused, coaxes brilliant performances from not only Humphrey Bogart but many of the supporting cast members, even those only appearing in one scene. The chemistry simmering beneath the surface of this entire film is absolutely intoxicating.

The story is an adaptation of a Raymond Chandler novel about a hardboiled private dick named Philip Marlowe who pulls no punches as he doggedly untangles a knot-riddled plot to reveal the fabric of the mystery. Because of perceived lurid content in the novel, enforcers of the Hays Code (basically a censorship board) followed the production of ‘The Big Sleep’ very closely to make sure all the choices were “morally acceptable.” Even with their attention, the content that made the cut must have been pushing the boundaries of the contemporaneous status quo. The story includes drug use, thinly veiled sexually charged dialogue, and allusions to pornography; but each so cleverly portrayed, it is as though the film itself is constantly giving you a side-ways glance with one knowing raised eyebrow.

The onscreen charisma of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall is undeniable, which makes it surprising to learn that several of the scenes where the two appear together were not included in the original cut. ‘The Big Sleep’ was shot during the final stages of World War II, but held back from release by Warner Bros. Studios in favor of releasing their backlog of war films in anticipation of waning interest in the subject matter. This gave the actors plenty of time to have other work completed and released. One of these films, ‘Confidential Agent’ starring Lauren Bacall met with negative critical reviews regarding her performance. In an effort to save her career, Bacall’s agent implored Warner Bros. to reshoot several scenes for ‘The Big Sleep’ to capitalize on audiences’ fascination with Lauren’s Bacall’s real-life relationship with Humphrey Bogart. This resulted in two different cuts of ‘The Big Sleep’-- the original and the theatrically released versions (with about a 20 minute deviation in content when added up) making the complex plot in the second version even murkier. The original was not seen again until 1997 when it was rediscovered, re-stored and released. Which is better? *shrug* It’s difficult to say. I watched both versions back in college, but one side of my DVD is scratched, and I was only able to revisit the theatrically released version. Critics mostly prefer the theatrically released version for the fantastic extra scenes with Bogie and Bacall, but also recognize the original, with its more understandable plot, as equally masterful.

The Maltese Falcon

(1941)

‘The Maltese Falcon’ was the first of six films that Humphrey Bogart worked on with director John Huston. Arguably considered the first major film noir, ‘The Maltese Falcon’ established in the public mind many of the tropes and clichés that were to become associated with the film noir genre: the hard mannered private detective with the downturned fedora, the weeping femme fatale, the starkly edged shadows, the quick use of colloquial turns-of-phrase, opened doors revealing guns held at waist level. It depicts these recognizable tropes so fittingly, ‘The Maltese Falcon’ almost reads as a parody of itself.

Humphrey Bogart portrays the lead, Sam Spade, a detective determined to understand who killed his partner and why, and as the plot thickens, he is confident that no matter what danger he finds himself in, he will undoubtedly talk himself out of it. Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade is instantly familiar, as he creates an archetype with this performance that almost every detective in every noir episode of every TV show still emulates.

Like many films noir, the cinematography is striking, often beautifully so, and captures exquisitely palpable, complex emotion. Scenes such as Mary Astor resting her head against the back of a couch while having it turned toward Spade as she lies through her teeth, presenting the picture of feigned pitiful exhaustion; or when Elisha Cooke Jr. leans in for a close-up with wide crazed eyes, tears threatening to drop as he softly demands that Sam Spade quit provoking him, offering the chilling portrait of quiet unpredictable rage; or the tableau of bitter disappointment depicted by two representations in one shot: Sidney Greenstreet standing befuddled in the foreground tugging on his ear while Peter Lore sobs dejectedly into a leather armchair in the background. Despite the rapidly paced dialogue, this is a film that takes its time, making the abrupt moments of action or violence more shocking. It is the detail of this film that delights and is not art to consume quickly, but to chew on slowly and savor.

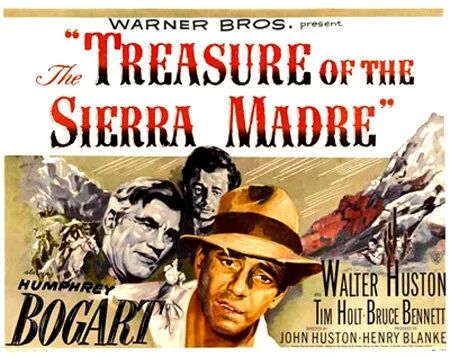

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

(1948)

Another John Huston film, ‘The Treasure of the Sierra Madre’ is an adaptation of a 1927 novel by B. Traven depicting three men played by Humphrey Bogart, Tim Holt and Walter Huston (John Huston’s father), as they journey through the Mexican desert in hopes of striking it rich by prospecting for gold. More so than any of the other titles on this list ‘The Treasure of the Sierra Madre’, moves through its plot in a manner akin to the pacing of more modern films. It is engaging from the very beginning. It opens with Bogart as Fred C. Dobbs, an O.K. guy who’s experiencing a string of bad breaks. It grows more exciting when circumstances for Fred and his buddy Curtin (Tim Holt) shift from begging for money to cover basic needs to the possibility of great wealth when they meet an experienced old prospector (Walter Huston). The two friends, with modest desires and a confidence in the integrity of their own nature, arrogantly dismiss the initial warnings of the prospector who knows how gold changes a person. As anticipation of quick and easy wealth swells, a fair three-way split between them, no longer appears adequate.

The cast is great with one significant caveat. Humphrey Bogart’s transformation from decent down-on-his-luck fella to murderous green-eyed monster is truly frightening and Tim Holt is likeable despite his compromises of character. That brings us the prospector: Walter Huston. As an actor, Walter Huston does a great job with the character, however the character itself is extremely problematic. On one hand, with his experience and wisdom, he operates as the anchor of rational thought and self-awareness, allowing him to provide much-needed moments of comedic relief. He laughs at himself, he laughs at his partners, and he laughs with the audience; and when his essential presence is removed from the formula, we know that chaos is eminent. It is the conceit under which he is removed that is the issue.

The film contains an egregious white savior B-plot that claims very little screen time, but significantly disrupts the viewing by its presence. A brief synopsis: Just as the trio are traveling back with their haul, they are approached by a few people from a nearby village that implore their help. A little boy has fallen into a body of water and will not wake up. The old prospector goes with them and performs some sort of weird procedure by pumping the child’s arms over his head. The child wakes up and the townspeople repay Huston’s character by feeding him grapes in a hammock in a manner not unlike worship. The casual way that this story is displayed, indicates that the film maker’s intention is for the audience to accept that an old prospector with no known medical background magically has the knowledge to save this child simply because he is white, and in the same way, that the townspeople have no practices of their own in these kind of dire circumstances, simply because they are not American and non-white. The depiction of the Mexican villagers as inept and seeking out the help of a white man, because any white man will do, feeds into the false and racist narrative of white superiority and non-white inferiority. ‘Treasure of the Sierra Madre’ is the vehicle of one of Humphrey Bogart’s best performances but also contains some of the most offensive material on this list.

Sabrina

(1954)

Amongst so many heavy roles playing the tormented cynic, the jaded detective, or villainous gangster, it’s a breath of fresh air to watch Humphrey Bogart showcase his comedic timing in Billy Wilder’s ‘Sabrina’. Despite being cast against type and outside his comfort zone, the humor and presence Bogart brings to ‘Sabrina’ works well and exhibits a rare, simple playfulness that’s just plain enjoyable to watch. Most of the humor in the script translates well today. Finding laughs in an unending determination to reach the last olive in a tiny jar, (gag found in the movie) will probably always endure.

The movie tells the story of a chauffer’s daughter, Sabrina (Audrey Hepburn), whose father works for a very wealthy family, consisting of aging parents and two brothers in their 30s, Linus (Bogart) the dedicated business man, and David (William Holden), the irresponsible playboy. Sabrina has been in love with David since she was a child, but he pays little attention to her, oblivious to her affections until Sabrina comes back from school older, more worldly and refined. David, however, is strategically engaged to be married, a union orchestrated by Linus as a business move beneficial to their family’s company. Determined to see this merger unhindered, Linus schemes to sway Sabrina’s affections with the intention of buying her off and sending her away. Predictably, as with any romantic comedy from any era, the caprices of love foil even the most practically minded of plans laid by the driest of stubborn mules.

Regardless of backstage conflict, the cast plays well off each other in a way that benefits the personality of the film. Audrey Hepburn does what she does best in all her pictures, her performance is rich with pure charm. It is easy for the audience to fall in as the remote fourth wheel of the Sabrina/David/Linus love-mobile.

*mild spoiler* On a personal note, although I found this movie very entertaining, I have one main gripe. The film fools the audience into thinking that this is Sabrina’s story, when in reality it is Linus’s transformation that represents the true center within this less fanciful ‘Beauty and the Beast’ type tale. A product of its time, maybe, but it mixes in a slight bitter taste into this otherwise easily consumable movie.

In a Lonely Place

(1950)

“I was born when she kissed me. I died when she left me. I lived a few weeks while she loved me.” A story of jaded screenwriter, Dixon Steele (Bogart), who is regarded as a genius that no one can get close to, at least not without great consequence. He is suspected of murder, which seems to put a strain on a budding romance between him and a neighbor, Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame) but, regardless of his guilt or innocence, his unstable temperament may be the graver threat.

In a Lonely Place is an adaptation of a 1947 noir novel of the same name by Dorothy B. Hughs which honestly deserves more attention. Not only ahead of its time in its awareness of a genre before it was identified as one, but also in its depth of empathy written from the perspective of a serial killer. The film deviates from the plot of the novel so considerably that very little remains beyond the characters names, and yet the atmosphere and insight of the novel are so effectively translated to the film that it could only be a product drafted from a deep understanding and reverence of the source material. As a result, both book and film stand hand in hand as notable companions, sisters maybe: both with different muscles and tissues that shape and define them but built from the same bones.

Film often stuns audiences with how masterfully a group of artists accomplishes the tremendous feat of making a movie, but only occasionally does it coalesce into something as poignant as ‘In a Lonely Place’. The film provides tone and mood as assorted as the multi-faceted personality of Dixon Steele. It sometimes feels like a romance, other times a psychological thriller and, then again, a tragedy; always keeping the viewers on their toes. The brilliant musical score, composed by avant garde composer George Antheil, supports the ebb and flow of mood so in sync with every other aspect of this film, that even a simple blink of Laurel’s eye gains its own story of meaning.

As might be expected from a film set in Hollywood about a brilliant, reclusive, and often violent screenwriter, the dialogue of ‘In a Lonely Place’ is equal parts punchy, elegant, and devastating. Humphrey Bogart’s nuanced performance depicting such a complex and deeply flawed character rivals few others as the most adept of his career. Both he and Gloria Grahame are generous with their performances which, captured by expert camera work, provides a depth and intimacy that engenders a feeling in the viewer of familiarity, as though they are acquaintances for us to gossip about later.

One of the most fascinating aspects in this film is the subtle understanding it has in its depiction of a violent personality; a personality that tends to manipulate and insulate within its own skewed reality. This understanding is shown in small, easily overlooked details, like how Dixon Steal buys gifts for the victims of his violence as a way of protecting his ego from the acknowledgement of his issues. Although characters in the film weakly justify Dixon Steal’s history of violence as part of the package with proximity to his greatness, surprisingly (for its time) the film itself leaves its intended sympathies murky. The story slowly departs from its centered focus on Steele as our understanding of him changes, and it becomes more aligned with Laurel and her impressions. Even though we’ve known Dixon Steel longer as the lead and have gotten a glimpse of his more intimate side, he remains an outsider, even to the audience, leaving us to cast our own judgements.

Bailey loves movies and hosts Austin based film podcast, Memory Static.