Deep Cuts: An Alternate Hyperreal Calendar

We’re beating the heat with a stacked summer series picked by Hyperreal Film Club friends and founders. This July, take a peek at what Hyperreal folks chose to pair with our official screenings—from dystopian English punks to clowns behaving badly and everything in-between.

Dick—BAPS

Dick (1999) is a classic of the bimbo microgenre that often gets overlooked for its more popular sisters, Legally Blonde (2001) and Clueless (1995). In these movies, young women are underestimated by society but ultimately display an overlooked skill set. Through the power of fun and friendship, bimbos save the day by revitalizing stuffy, male institutions.

Anyone interested in the bimbo renaissance should do themselves a favor and check out B.A.P.S. (1997). B.A.P.S. (short for Black American Princesses) has the Y2K outfits, the social satire, and the joy of your favorite girly movies, while also boasting a rare no-star rating from Roger Ebert and a 15% on Rotten Tomatoes. Movies where Black girls get to have the innocence and fun of girls like Elle Woods and Cher Horowitz don’t get made enough, and when they do they suffer the indignity of Roger Ebert’s “Most Hated” list.

The current bimbocore trend is more political than ever, from creators on TikTok citing theory on the male gaze to Barbie spouting feminist platitudes in her record-breaking blockbuster. Hopefully, this emphasis on politics will have racial justice components. The bimbo canon of the 1990s and early 2000s was overwhelmingly white, but we have an opportunity now to reevaluate gems like B.A.P.S. and open more doors for Black femme movies to thrive in the future.

Orlando—Maurice

“Do not fade. Do not wither. Do not grow old.”

When summing up Orlando (1992) following my first watch in December of 2022, I succinctly described the Sally Potter film as “thee gayest thing I’ve ever seen.” An androgynous, immortal, sex-changing Tilda Swinton pursues knowledge, art, and love over the course of 400 years in the Virigina Woolf adaptation. It’s a true gender-bender, tapping into the imagination and playfulness of queer identities via an English nobleman.

In Maurice (1987), a young James Wilby plays the title character, maneuvering his coming-of-age as a gay man in the early 1900s. Similar to his fellow Orlando, Maurice comes up against cultural standards and subsequent legal threats in his home country of England. Both of these features offer an exploratory approach to desire, subverting traditional period pieces and celebrating queerness. Maurice and Orlando are both moody, tender, and stymied by the archaic constraints of a so-called modern society, choosing to bravely seek out their own joys. Not to mention, both films are distinctly beautiful—particularly Orlando in dress and Maurice in cinematography.

Cloak & Dagger—The Last Starfighter

If you were gripped by the stellar thrills of Cloak & Dagger’s (1984) dark, child-focused espionage, you’ll love the interstellar frills of The Last Starfighter (1984) and its dark, teen-focused war story. Alex Rogan is on the precipice of adulthood. He’s outgrown his stomping grounds and now he passes the time waiting for his college admissions letters by playing the video game Starfighter. Unbeknownst to him, the game is actually a secret recruitment tool for an intergalactic defense force, and Alex’s mastery of Starfighter signals his draft status as eligible. Much like Cloak & Dagger’s protagonist Davey, The Last Starfighter’s Alex is called to a higher purpose by machinations beyond his comprehension. If he fails to answer the call, the whole star system could be lost to the evil alien Xur.

Using cutting-edge CGI, practical effects, and dark elements mixed with adventure and comedy, The Last Starfighter is the next frontier for those seeking another gripping story of innocence lost to extraordinary circumstances. While the CGI hasn’t aged gracefully, the colorful characters, solid laughs, and moments of genuine shock make The Last Starfighter one small step for our inner child’s continued maturation and one giant leap toward validating all the hours our outer adult has spent playing video games.

Deadly Weapons—Dangerous Men

John Rad’s Dangerous Men (2005) doesn’t have time to set up its characters, doesn’t bother to pave any substantial path on its road to revenge, and it doesn’t even manage to hold onto its core cast for the entire runtime—but that makes it the perfect alt to Doris Wishman’s Deadly Weapons (1974). If you watched Deadly Weapons and thought I don’t know what I expected, it’s exactly what was advertised, that’s thanks to Wishman’s laser-focused approach in rendering a methodical tale of vengeance with a Chesty Morgan-sized bust. And as the old adage goes, you’ve gotta have your valleys to appreciate your peaks. Dangerous Men is the valley that will help us appreciate Chesty Morgan’s peaks.

Dangerous Men tells the story of a woman scorned, her lover brutally murdered, her heart set on revenge; the key difference between the similar stories of these films is John Rad’s filmmaking faux pas. His pacing suffers from eagerness, his character motives are obscured by oddly imperative dialogue and decisions, his score is clearly taken from an unrelated ToeJam & Earl title, and all of it culminates in an audience that’s left thinking I don’t know what I expected, but it wasn’t that. The stark difference in how Rad and Wishman represent a “damsel turned demon” and the dark paths they follow when their characters are pushed too far enables an elevated appreciation of both features and an educational experience in what gives exploitative revenge plots more weight—and it’s not just a larger bust.

A Night at the Roxbury—The Last Days of Disco

Throughout A Night at the Roxbury (1998), Steve and Doug Butabi are chasing dancefloor wishes and nightclub dreams. To everyone else, their obsession is inane and fruitless, no way to live a life. But the ensemble of yuppies from Whit Stillman’s The Last Days of Disco (1998) might say otherwise; after all, to quote the film’s tagline, “history is made at night.” Steve and Doug exhibit a nostalgia for an era they just missed by a couple of decades: the age of disco, a time for people of all walks of life (besides advertising executives) to come together and celebrate life under the disco lights. Alice and Charlotte (Chloe Sevigny and Kate Beckinsale) couldn’t be more different than the Butabi brothers: Ivy League graduates spending their days working at a publishing company and navigating life in a distinctly 1980s New York, unaware that those days they’re whiling away will soon come to close. They’re the kind of women that would push the Butabis away in disgust and turn back to their philosophical conversations about social politics and Disney movies. But all the same, they’re in that nightclub, too; the Roxbury and the unnamed Studio 54-inspired club are both sanctuaries, utopias of dance.

Though Disco received much more critical acclaim than Roxbury—the former being added to the Criterion Collection in 2012 and then receiving recognition from Vanity Fair on its 20-year anniversary, and the latter being dismissed as one note and forgettable—both of these 1998 films deliver that familiar feeling of wandering through your early 20s, just trying to have as much fun as you can while also trying to be taken seriously by your peers and superiors. Stillman’s humor is much drier than the SNL-esque punchlines, but it still veers into the absurd, such as when Alice seductively murmurs that “there’s something really sexy about Scrooge McDuck.” It’s not unfeasible that the two movies live in the same universe; Disco’s Josh predicts that “disco was too great, and too much fun, to be gone forever! It’s got to come back someday. I just hope it will be in our own lifetimes.” Hopefully, the older versions of the yuppies found their way to Mr. Zadir’s inside-out club. In the meantime, throw on either soundtrack and dance your troubles away; after all, before disco, this country was a dancing wasteland.

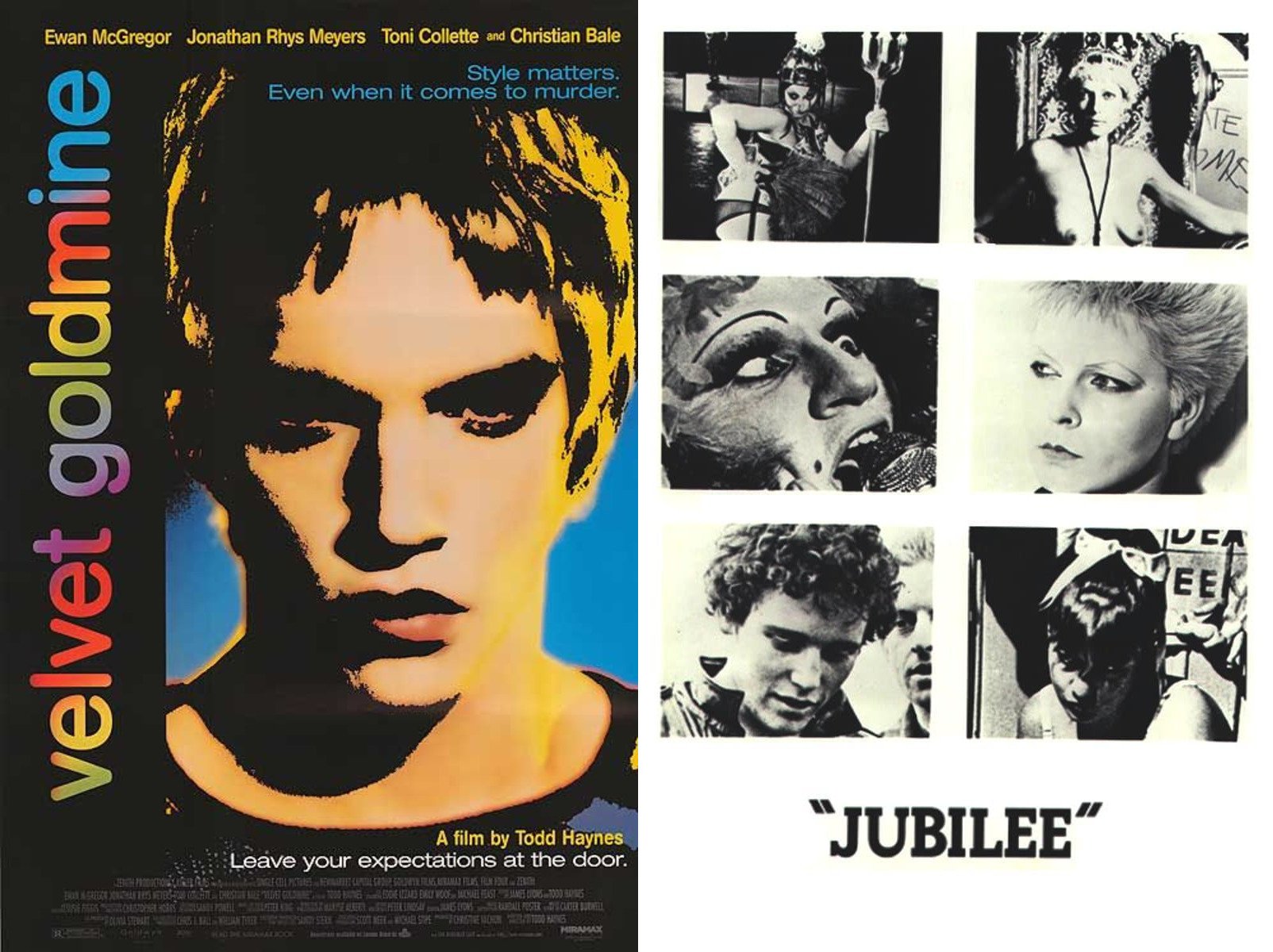

Velvet Goldmine—Jubilee

Todd Haynes’s Velvet Goldmine (1998) is what I call decadent for those who love a movie that has a little bit of everything: a well-picked cast playing roles that you wouldn’t expect them to be, a music score that is essentially perfect making the audience nostalgic for an era, and an overload of beautiful visuals one would simply adore. It’s easy to come out of this movie with the assumption that you just watched a music video in the form of a well-packaged movie. The movie can be summarized as Citizen Kane that takes place in late 1970s Britain but way more queer, way less serious and way more excitable. We follow a young Christian Bale journaling about esteemed icon Brian Slade (pretty much David Bowie played by Jonathan Rhys Myers) and his rise and downfall as a celebrity. I would say that Haynes hit gold (hehe) with this movie, making a mark on queer cinema, although it was initially a box-office failure. It’s an immediate classic for those who love music, queerness, David Bowie and spending hours watching music videos.

For those who relish everything that this movie has to offer or want to see something in a somewhat similar vein, I highly recommend Derek Jarman’s Jubilee (1978). While not an ode to a previous decade, Jubilee itself takes place smack dab in the time that Todd Haynes was leading the audience to visit right alongside punks of London. We watch these punks of London and Queen Victoria embark on a journey of what London’s dystopian scene was like in the 1970s. Both films share an eccentric soundtrack—Jubilee’s score is composed by the one and only Brian Eno, who is heavily showcased in Velvet Goldmine. Alongside a stellar OST, both of these movies embark on a semi sci-fi theme every so lightly. However, as much as Velvet Goldmine is somewhat light-hearted, Jarman’s audience will be thrown into a more dark path. Nonetheless, it’s a perfect companion piece to Velvet Goldmine and worth the watch.

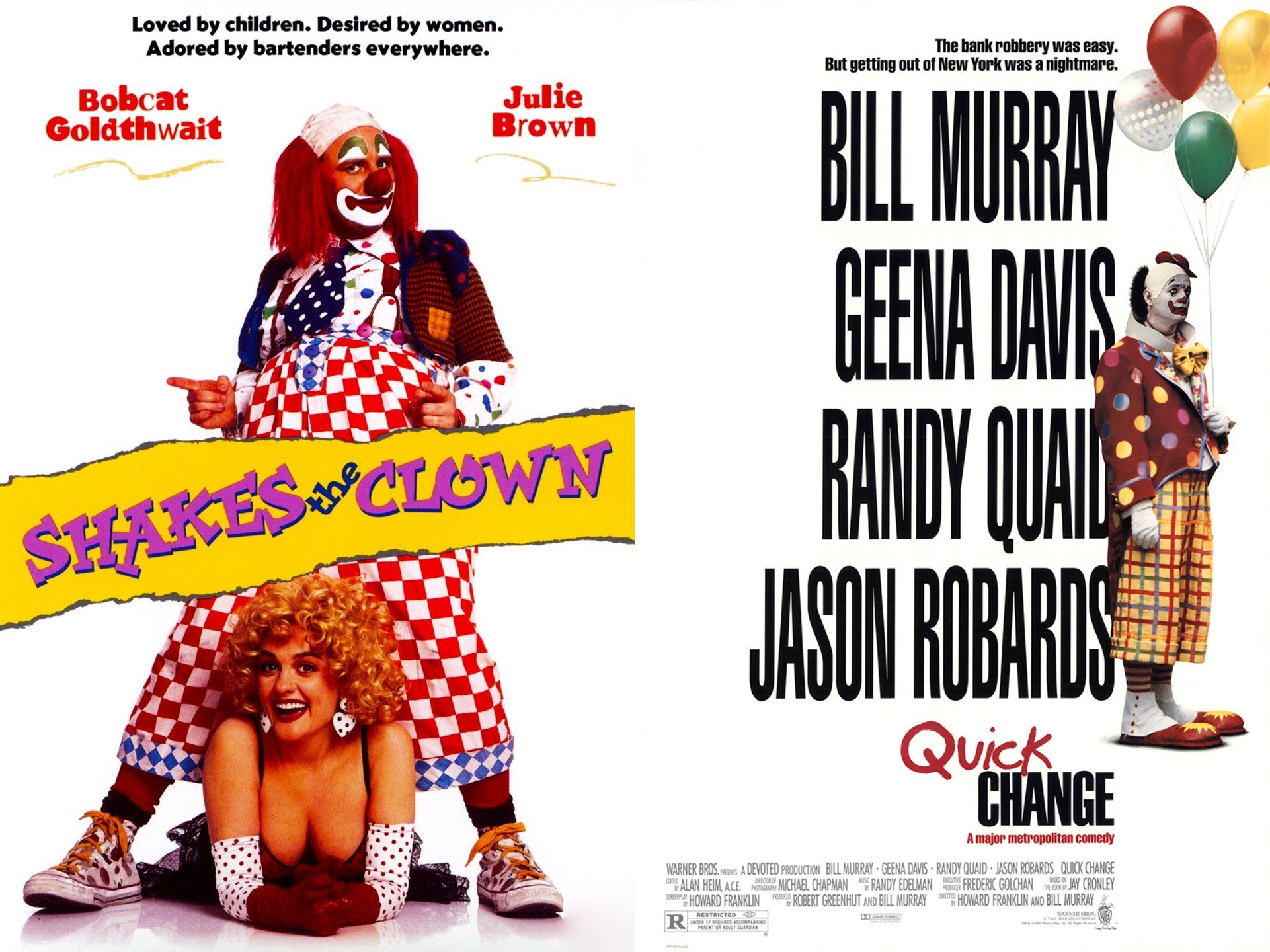

Shakes the Clown—Quick Change

As a self-declared connoisseur of the niche genre “clowns behaving badly,” I felt compelled to suggest the underrated Quick Change (1990) as a companion to the “the Citizen Kane of Alcoholic Clown Movies”: Shakes the Clown (1991). Both were directed by their comedic stars, Bobcat Goldthwait (who went on to direct many films) and Bill Murray (who never directed again), and co-starred curly-haired babes with beauty marks: Julie Brown and Geena Davis, respectively. The cameos are delightful: Robin Williams as a mime instructor and Phil Hartman as the Manhattanite who’s been ripped off one too many times, among many more. Made just a year apart, they use the metaphor of a clown to comment on the malaise of everyday life. Relatable!

While Shakes lives in a world where clowns are everyday working stiffs, Quick Change is set in New York where being a clown is a total joke. It kicks off with Bill Murray in full clown drag riding the subway on his way to rob a bank. In my favorite exchange, the security guard asks “What kind of clown are you?” “The crying on the inside kind, I guess.” He then does the worst thing a clown could do: hold up a pekingese at gunpoint. Antics ensue and suddenly you’re on the run trying to make it through the mean streets of NYC to a plane bound for Fiji. Shakes also runs from the law after being framed for murder—and if you didn’t believe ACAB before, you will after seeing the lack of respect law enforcement has for our face-painted friends.

Near Dark—Let Me In

Kathryn Bigelow’s directorial debut Near Dark (1987) explores the fateful consequences of chatting up strangers. A bored young cowboy hits on a seemingly shy young woman passing through his bump-in-the-road Texas town and winds up with more than the usual Friday night fluid exchange. Railroaded into a shotgun wedding of sorts by her nocturnal family of Western-styled bloodsuckers, our hero is forced to reconcile his small-town values with his new dietary requirements and the complications of young love.

Matt Reeves’ Americanization of the Swedish horror film Let the Right One In follows another lonesome young man longing for connection, while leaning into the 1980s tropes that Near Dark comes by naturally. Set at the height of the “satanic panic” that gripped suburban America during the Reagan years, Let Me In (2010) follows a young bullying victim as he befriends a strange girl, Abby, who has just moved into the apartment next door. Both are outcasts, being raised by single parents, drifting through a world that has no place for them. But Abby’s adult guardian is actually her pitiful servant, venturing out night after night to murder random victims and drain their blood for his voracious charge. After its initial release, Let Me In received criticism for being too similar to the original Swedish version (itself an adaptation of a novel by the same name). But Reeves’ film stands on its own due to the intensity of its performances and its dread-inducing evocation of 1980s conservative paranoia. It’s 10 o’clock—do you know where your children are?

Face/Off—Twin Dragons

John Woo’s Face/Off (1997) is a touchstone film for me. I watched it while in college at The University of Texas at Austin. I was certainly plastered as I watched Nicolas Cage/John Travolta just rip lines of dialogue like, “I can eat a peach for hours” out of the park. It was the film that introduced my bumpkin brain to Hong Kong-style action. I had seen similar but watered down versions like Shanghai Noon, but those have since been wiped away by an explosion.

I started with watching other John Woo films, some that Hyperreal has shown in the past, then moved on to a plethora of other directors. However, the movie that may have had the most influence on something like Face/Off would have been Ringo Lam and Tsui Hark’s Twin Dragons. Released in 1992, the film stars Jackie Chan with a similar high concept where he plays twin brothers separated at birth. Both Ringo Lam and Tsui Hark worked with John Woo in Hong Kong and all had a similar Hollywood strategy. All three had American debut features starring Jean-Claude Van Damme, but sadly only John Woo made any big waves in the American box office. So, please go back and watch this exciting Hong Kong action film co-directed by UT Austin Alum Tsui Hark! Who knows, there may be an exciting boat chase in this one as well.

Southland Tales—Sorry to Bother You

Southland Tales participates in a type of absurdity that is mind melting. Hearing lines like “there would be a lot less violence in the world if everyone just got a little more cardio” and “that is the primary reason why I won’t do anal” pinging around near-future dystopia Los Angeles comes across more as a crude joke than a political theory. That isn’t to say the film doesn’t have worthwhile ideas, but when comparing the 2008 comedy to Boots Riley’s 2018 Sorry to Bother You you will find the latter is more mind-expanding.

If Southland Tales uses absurdity like a hammer, Sorry to Bother You is a drone strike—an expertly crafted social satire using magical realism to its fullest. Its political ideology is concise with a true revolutionary as auteur. Riley effortlessly melds theory with story for an absolutely bonkers ride through Oakland, following LaKeith Stanfield’s Cassius Green from lowly call center scab to war criminal landlord. Sorry to Bother You is a film that has my highest recommendation and I think anyone will find even greater joy in lines like, “God made this land free for all of us. Greedy people like you want to hold it for yourself and your family.” Especially when in response Terry Crews says, “Cash, I’m your fucking uncle.”

Louise Ho can be found as @latewithcoffee on letterboxd