Getting Hyperreal with... Ryan Darbonne

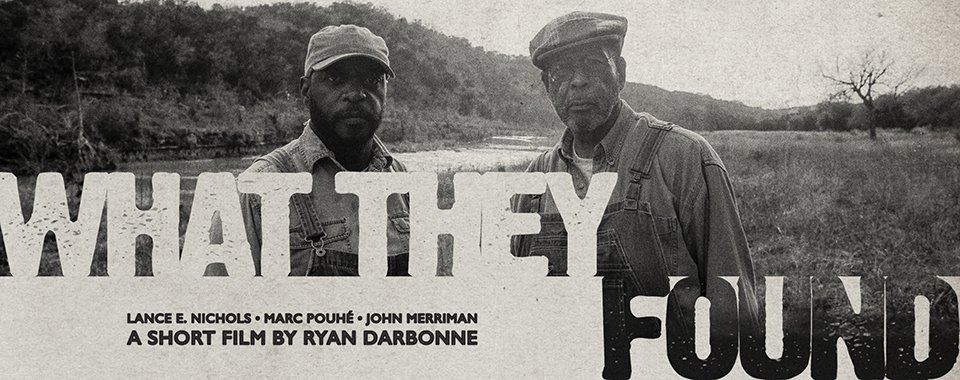

Hyperreal Interviewer extraordinaire Justin Norris sat down with filmmaker Ryan Darbonne to discuss his short film What They Found, authenticity in period piece filmmaking, and watching The Banshees of Inisherin in Ireland.

Editor’s note: This interview has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

Hyperreal Film Club (HFC): Let's talk about What They Found. One of the first things that caught my eye was the visuals. The first time I watched it, I was like, is that a dummy or is that an actual person?

Ryan Darbonne (RD): I think part of that, especially with the body, I think if we had skewed gorier or grotesque, it then would have kind of been in that weird “This is not going to look as good,” space so I think I wanted to keep it real simple. One of the biggest inspirations for the look of the body was Stand by Me, where the body was just simple. It was eerie. You didn't really get a sense of how this person died, you just know that they're dead, right? And that's kind of what we were going for. To me, especially with shorts, and especially shorts on a limited budget, simple is always the best answer.

HFC: The film itself throws out this super engrossing idea of what happens when you come across a dead body. Going off that, what was kind of the inspiration behind What They Found?

RD: The original idea for What They Found was set a few years after the Civil War and it was about two kids who find a body out in the middle of Louisiana. The whole idea was that this body, we eventually find out that the body is actually protected by a golem. I'm from Louisiana and in a part of the area that I'm from, there was an uprising three or four years after the Civil War where a bunch of white people got mad and killed a bunch of Black people. But it was one of those uprisings that you never hear about, right? It's just a lot of them popped up throughout the South and this is one of them. It was close to home for me because this is literally where I grew up and where I spent summers and everything, so it was kind of supposed to take place in the middle of that. These kids find this body and find out that this body is a golem and I really liked taking this sort of Jewish mythology about a golem - which is a monster built to protect oppressed people - but taking that and flipping that on its head with free Black people. There are a lot of reasons though I think we didn't end up doing it that way because one, it would have been fucking expensive! Like really expensive. And dealing with kids. I don't know why I had it in my head like, “We can do this” but then I was like, “There’s no fucking way we can do this on this budget!” and so I started to think, “How do you simplify this?”

So we got rid of the supernatural element and then I was like, oh, it'd be interesting if two white guys find a Black guy and thank God I had a really good friend who's also a writer because she's like, “No, that's a stupid fucking idea. Like, don't do that. That's fucking dumb” and I was like, “What do you mean?” And she was like, “Well, there's nothing at stake, right? They could walk away, and it'd be fine and not a big deal,” and I was like, “Oh, that's a good point!”

So I started to think on things that inspired me and there were two things that came to mind: One was The Seventh Seal, directed by Ingmar Bergman and then the other was this short story by Raymond Carver about a group of guys who go on a fishing trip and they find the body of a woman and she's bruised and she's naked and she's just floating in a lake and they don't know what to do. They end up tying her wrist to a branch so she doesn't float away and they spend a weekend fishing and just fucking around and doing whatever but then the story is from the perspective of the wife of one of the men who found the body and he's telling her this story and she's like, “Well, why didn't you do anything? Why didn't you help?” and he says, “Well, she was already dead, and we ended up calling the sheriff anyways after vacation,” and then it becomes about this wife being obsessed with this woman and you find out how the woman died and she goes to the woman's funeral, but it really is this bigger story on misogyny. It ends kind of depressing because she has this whole new view on her husband and she's like, “Is this guy right?” so I was inspired by that, too.

The Seventh Seal

If you've ever seen the movie Shortcuts by Robert Altman, it's a fucking fantastic film, but that story by Raymond Carver is in Altman’s film. So those were the inspirations for me and I thought, how do you have these bigger questions of what do you do? What's at stake, right? For these guys who were fishing, nothing's at stake. They called the sheriff, and everything was fine but if it was two Black guys, you know, there's a lot at stake here and we need to be careful on how we play this whether the worst will come to fruition or not. It's sort of like what do we do, right? It's more than just calling in a dead body and so I liked exploring that idea of, even in death, white supremacy still persists. Like this guy is dead, he can't physically harm them, but he actually still can.

HFC: Going off that short story you mentioned, did you ever think to make the dead body a white woman? Did that ever cross your mind? Because I feel that could create another interesting, well I hate to use the word “interesting”, but another layer that adds on to what August and James discover?

RD: I think I did and I think I decided against it for two reasons: One, I think it just added a whole other complicated layer to it where I don't think we could tell that story in the short. I also wanted to explore where the situation becomes this weird triangle relationship between men. Even though there's a body and he can't talk, it's still dealing with these three men in a way and that idea interests me more. But definitely, 100% I was like, oh, yeah, it would be interesting. Like how would that play? But I think the film would lose some of the comedy a little bit too because it's easy for them to dismiss [the body]. You know, it's a dead body and they’re having this conversation, right? And I think it's a little harder to suspend disbelief if it was a dead white woman.

HFC: Was What They Found always going to be a short? Or did you have a grander vision that you had to scale back?

RD: No. Which is funny, because it's kind of one of the first shorts I've written and done where I didn't think bigger, it was just sort of—I mean it kind of ends open ended, but I just wanted to keep it self-contained. I don't know, maybe I think at some point I might think of a grander idea because I really liked those two characters a lot, James and August, and there's a lot of backstory into the relationship and a lot of things that we had to cut for time. I will say this: this is probably the hardest film I've ever had to edit just because it's that balance of finding a rhythm with how they speak to the point where we would literally cut out words and combine words to make new sentences and it just took for-fucking-ever and I think that we found a good balance but then there are things that I wish we didn't cut because it gave more context to their relationship and kind of their past and stuff. But if I was going to do it bigger, I would explore more about them and kind of that dynamic.

HFC: When it came to creating this short, did it start with these characters specifically? Or was it just the scenario and you came up with the characters later?

RD: Yeah, it was a scenario and thinking, okay, well, they’re either hunting or fishing, and the fishing came from the short story. James is named after my grandfather and August is named after a playwright, August Wilson, and from there it was sort of like how do I figure out these characters and writing shorts is so silly sometimes because I have this whole backstory relationship that we're not really going to get. I know it helps for the actors, but we have such a finite amount of time to tell a story that is really worth it, but you know, I did it anyways.

Going into it, I had to be careful because it was easier to kind of side with August a little bit and give him the heavier monologues and I just checked myself. There had to be more balance. There has to be flaws on both ends and you can kind of see both perspectives, right? Instead of just making James the sort of weaker person and Marc [Pouhe], who plays August, he was always in mind for that character. He's a theatre actor in Austin, he's phenomenal, but he's just like this big Shakespearean dude and you know, it would be easy for him to overpower the scene if I just gave him more stuff and there's a subtlety to James that I like, and a lot of stuff we cut out, James was a little more condescending to August. The whole thing with them, you kind of get this sense that - and it's a little bit in there now - but you get the sense that they kind of came up together in the Civil Rights Era because the film, and it never says it, but the film takes place in ’84. We had this whole backstory that August didn't march or do anything just out of survival. He was like, “I'm not going to be involved because I don't want to die.” James was the one that was involved and more active and I think that there's tension between them, right? Where it's like, well, you never did anything, what are you complaining about? That's why he's like, “You're making these big grand statements about white people but it's like, you didn't do shit, you didn't do anything.”

HFC: As a filmmaker, and as a person creating stories, especially ones that are thematically loaded by real life stuff, what do you think of always trying to find that even ground of getting two sides of an argument? Do you feel you always have to even it out for both sides of a particular discussion. I was just curious if you've ever done that on other shorts you've worked on?

RD: I really like that question because I think it's all about perspective, right? And this one was clearly a two man show. But if we were like, oh, this film was about August, then yes, it would be fuck everything else, this opinion is right. I mean, it would honestly be the same if I were writing a fucked up racist character and it was through that perspective. You have to double down on that because this is what they believe and this is who they are and other opinions don't matter and if we're seeing it through the perspective of their eyes the whole time, then I want you to sit with that and sit with who they are as a character regardless of how fucked up it is whether or not you as an audience member agree or not. Again, like those are some of the more interesting things where, yeah, you could show all sides of the perspective but if we're with a character, and this is our main character, and it's not a sort of ensemble piece or two person piece, then yeah, I would just want to explore this one side and double down on this idea of the character. I guess it's a similar feeling to actors who play racists or slave owners, right? Where they're like Leonardo DiCaprio in Django Unchained. He didn't want to say the N word, right? But Sam Jackson was like, “No, fucking do it. This is your character!” You know what I mean, it would be silly. As fucked up as it is, it'd be silly not to.

HFC: Correct me if I'm imagining this wrong. If Leo was to go that route, where he doesn't embrace that character’s racism, so to speak. In a way, it's almost like erasing the past. Avoiding the past.

RD: Have you ever seen Mid90s? The Jonah Hill movie? They use a lot of insulting language, right? Like homophobic slurs and all sorts of shit, and [Hill] got flack for that but, man, I can defend it because that was how we talked back then. I grew up in that era and that’s just what it was, for better or for worse, right? Some people don't grow out of that unfortunately, but you get older and hopefully you understand your words have impact and it's a whole wide world out there, but I think Mid90s is so accurate to being in middle school or being a freshman in high school in that era, and just talking like that, and you know, none of that was from a place of hate, just ignorance, right? So, if you were to do away with that, it would erase the past, but it would just be, I don't know, it'd be fucking corny! [Chuckles]. If you have a grounded drama set in the nineties, you're going to have to speak the way people spoke back then, right? Just like the way people spoke in the Civil War or in the 40s and the 50s. If we were to erase those words that make people cringe, I think we would erase the past and we wouldn't learn from the past. It's like the whole debate with critical race theory. We don't want to learn these really fucked up things because we don't want to take accountability, you know what I mean?

Mid90s

HFC: Circling back to the conundrum August and James find themselves in, I wanted to get your perspective on if you thought there was a right decision to be made from one of those two characters in What They Found?

RD: Yeah, to the latter question, the first thing that comes to mind, and I don't know if this is a great example, but let's say you're a white woman and there's a group of Black kids doing something that makes you uncomfortable. They're like smashing car windows or some shit. And let's say you consider yourself like a “woke” white woman and you think that “Oh, I'm with it,” but then it’s like, you have a choice. These kids are doing something kind of fucked up and they’re not just kids selling lemonade or whatever, but you know that if you call the cops that some shit could go down, and you can be the cause of somebody's death, right? And they're not necessarily harming someone and maybe they’re harming property but then it gets to the bigger question of “Is property more important than a person's life?” and all these things. So yeah, I feel like there's a lot of gray area. That's sort of the maliciousness of white supremacy. It really affects everything. It complicates so many things, right? It's not just like the cops have come down, telling the kids to stop. The cops have come, and they can literally shoot one of these kids, if not all of them, right? It just becomes so much more complicated. Especially with everything going on, especially it being a white woman in danger. Did you ever see the show Lovecraft Country?

HFC: Yes.

RD: The show is great! But in the book you get a lot more internal monologues with the characters and there’s a whole bit in the show where a Black woman changes into a white woman. And in the book, when she first does it, she's a white woman and she's having this internal monologue and they kind of showed it a little bit in the show, but a Black kid bumps into her and a cop is like, “What did this kid do? Are you okay?” In her mind, she's thinking in the book, she's like, “Well, literally I could say one word and this kid could just be ruined for the rest of his life, right?” This power of white women is kind of what the monologue in her mind was talking about and so yeah, I think there's a lot of gray area when it comes to that kind of stuff. To your first question, a part of me thinks that they could have just walked away. Part of me thinks it's kind of anticlimactic, you know? James goes to call the cops, August walks away. Nothing happens, you know what I mean? Or they both walk away!

HFC: There's this book, you brought it to my mind. It’s called Black No More by George Schuyler that came out in 1931. It's not a long read, it's less than 200 pages, but the whole setup is there's an invention made that turns Black people white and then the whole book is just this analysis of America where all these black people decide to take part in this invention. There's a moment at the end where two white men, as they’re trying to hide from angry mob out to get them, they decide to do blackface and pretend to be Black. But they do it in a backwoods, anti-Black town where this town of white people eventually catch these two white guys in blackface and proceed to execute them publicly because they think these two white men are Black. The book describes how they're mutilated and then all the people are like gnashing at the teeth to do it. But that final moment in What They Found, with August and James, it just kind of brought up those real-life atrocities committed against Black people and sort of flipped it on its head in a way sort as these two Black guys get to relax, while there's this specter of death right next to them when in real life, it was the opposite: white people would approach the death of black people recreationally.

RD: To that point, you should read this short graphic novel by a guy who's based out of Houston. It's called Incognegro. It’s based off a true story about a real-life journalist who was light skinned enough to where he could pass for white and he went into the South and he was reporting on these lynchings and stuff because obviously they weren't reporting on it and writing about it in regular news sources. It's a really interesting graphic novel! Just the backstory behind it is really cool. But yeah in regard to the ending, I think it's more symbolic than anything. It definitely is dark. I mean, race aside, it's like there's a dead body and there's two guys playing a domino game!

HFC: There's a couple of literary references in What They Found. In general, there’s a lot of references to other works of art in August and James's performances. There was a certain grandiose element to this short, even just in the idea of finding a dead body and figuring out what to do. Were you kind of aiming to push this story into this sort of operatic atmosphere?

RD: 100% dude, like you got it. The dialogue is even a little unnatural in the way they talk, like no one really speaks the way they speak, right? That's by design. I wanted to have a very stage play sort of feel to it, so it is kind of this big, grandiose kind of way in which they speak as if they're speaking to a live audience. There's a rhythm to how they speak and I mean, I've spent so much time going over literally every single line that they say, and there is a flow. It's sort of inspired by Ralph Ellison, and how he wrote and was inspired by jazz and the movement of jazz.

Admittedly, some of the way I had it in my head definitely gets lost in the translation when you start to edit because again, you're sort of bound by the rules of the short. It could have been a lot longer. It could have been a 20-minute piece. We made a short, but it can't fall beyond this length because there's the unspoken rule of film festivals. It's got to be this length or less even though they say a short film is 40 minutes or less but really, they just want a 15 minute or less short. You sort of just have to play that game and it can be a little frustrating sometimes and I would have loved to have made this 20 minutes long if I could, just to let things breathe a little bit more and stretch out a little bit more. But we couldn't, so I think some of that rhythm and that flow gets lost a little bit because we had to cut things out. But yeah, it’s definitely by design just in how they speak. It’s not supposed to be a natural way of speaking.

HFC: As a filmmaker, with the way this film touches on America's race relations and how it plays into sort of everyday decisions, did you feel like an air of responsibility to kind of do this story right?

RD: That's such an interesting question and something I think about a lot. It's sort of like, what's your responsibility as a filmmaker of color, right?

HFC: Do you think that’s fair? To be asked that?

RD: No. Not at all. I think we get put in those positions because, again, just by design and how systemic racism is, I think you feel the need to have some responsibility. You hear a lot of filmmakers talk about, especially from filmmakers of color, talk about, “Oh, I don't want to do trauma porn anymore. I just want to be able to make a film, like a romantic comedy or whatever without the weight of this thing.” But unfortunately, you could do a fucking straightforward romantic comedy, no implications of race or of socio-politics or whatever, but I think by the nature of making your characters Black, it becomes political, regardless of if you want it to or not. It's just the way the fucking world is, unfortunately. So, I tend to err on the side of no, I don't feel responsible to anyone but myself and the story. But I will say this, if I were doing a film and a character dealt with, and this is a really extreme example, sexual assault, I would feel a responsibility to not be flippant about it but be honest and authentic about it to try and make sure that these are real, valid experiences, and to just do a sort of one-dimensional portrayal of that would be really fucking shitty.

So, there's a responsibility to that. I think as a Black filmmaker, I just want to be like, it's my experience, there are a lot of very similar experiences and the best I can do is just hope that somebody connects with it in a way, right? But the key point is I don't think it's fair at all. Because, you know, my God, what if we fail and it doesn't connect with audiences? Again, this idea where we get put on this pedestal like, well, you have to achieve this level of Black excellence. It's like, fuck that, I want to be Black mediocrity! Right? I want to be able to take a fucking massive swing and do this weird off the wall shit and if it doesn't land, it doesn't land. It doesn't have to be responsible to anyone. Once you put your art out there, you lose ownership of it a little bit. I just want to write as good a story as that stuff that means a lot to me. So if I can do that justice, I feel proud about that and hopefully other people can connect in a way to that too.

HFC: When it came to working with the actors of August and James, you said you kind of had their backstories in mind already. Working with these particular performers for this film, how did you approach that? Did you tell them, “I have this vision of these characters, I want you to do it like this” or were you pretty open to how they had any interpretations and changes that maybe might have surprised you?

RD: I don't mind improv! With this, I wanted it to be pretty strict to the words on the script because of that flow, but like Mark, for example, who plays August, I had him in mind when I wrote August. I already had an idea of how he was going to play it and he played it almost exactly how I envisioned it! With James, that was a little different. We had another actor for James, who was a younger person. And he was phenomenal, and he was great, but he had to pull out for scheduling reasons. So we kind of had to skip their shooting day, which all ended up working out for the best. But he played it very differently. So, when he had to pull out, I was like, I don't want to try to force someone to play it the way he played it, even though he was really good and had a great dynamic. It just wouldn't be fair. So, Lance [E. Nichols] is based in New Orleans and I have a friend in New Orleans and he connected me and Lance and Lance has been in a bunch of shit. Lance was in all four seasons of the show called Tremé on HBO. He’s in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

We got suuuuper lucky because he was like, “Look, I'll do it for way below my normal rate and as long as you could put me up at a hotel, which doesn't have to be super fancy, and pay for my ticket and fly up me there, I’m game.” The first time we actually met in person was the first day shooting, and it was great and Lance did it exactly how I wanted him to do it and he was just very calm. He's very calculating in what he's saying and I think August is just all emotion and he definitely played it out.

It also kind of goes back to that idea of you having limited time and limited money and you have to get things done very quickly. Would I have liked to have more time? 100%. 100%, because I think we could have found more stuff to play with. But yeah, just the blunt truth is you just kind of have to get what you get and hope for the best and luckily, they were professionals, and they were great, and they knew this shit. But yeah, I think you can always get more.

HFC: You mentioned that you had this backstory for August and James, and just more depth that you had in mind that wasn’t able to be shown. Did you have the same sort of background lore for the body? The dead man? Was there any sort of background in how he got there? Or did you mainly see him as just this purely symbolic object to act as the thrust for the story?

RD: Yeah, it was that because I didn't want to give, even me as the writer, I didn't want to know anything. So, it's very vague. We don't know how he dies. You know, there is a semi supernatural element to it, and this is a small filmmaker-y, jerk-off film school thing, but I was very adamant about not having the sound of flies or him smelling even though he's decayed, right? It's little things like that. There are no fly sounds in the sound mix or anything like that.

HFC: So when looking for a location, did you have this particular location in mind? Or did you have a visual frame of reference that was operating in the back your head?

RD: The original plan after this version of the script was written was to shoot it in Louisiana because that's the kind of setting I wanted. Something that had a little swampy, misty, kind of nastiness to it. Then again, budgetary constraints and the hassle of carting a whole fucking crew down to Louisiana and then finding a good location and then finding places to stay, it would’ve been a bigger issue. So, I got super lucky! I just kind of put out a feeler on Facebook and where we shot was a friend’s ranch, their family owns that ranch out in Kyle. It was far away from their homes and stuff and you couldn't see power lines or anything. It truly felt like they were alone in the world and even with the sound, the only thing we had to contend with were planes flying overhead sometimes and that wasn’t even that bad. But we didn’t have to worry about highways or cars or anything. It was quiet and it was great!

There was one time we were shooting and we were on the Brazos River and we were shooting and I remember, across from us was just woods like across the river, and in the middle of the take we just heard what sounded like children laughing in the trees. It was very eerie, but it turned out to be coyotes. We didn't see them, but you could hear them. It was like, damn this is so fucking weird! A part of me wishes we could have shot in Louisiana but there's something nice about having this big openness to it because I think it heightens that isolation for both characters just a little bit.

HFC: There's something tense about being the only thing in an open clear space. For August and James, it's open, but it's just them with the body. It's still compact, even though objectively they’re in an open field.

RD: Well, that goes to the stagey aspect. I mean, even the way it's blocked, they’re pretty much stationary for the most part and that's kind of by design. You have this big open space but we’re really just right here and they really don't move from this position except maybe a couple times. That was very intentional to just try to set it up almost like a stage play in a way.

HFC: How long did it take to create this short? What was the most time intensive part? Was it the editing?

RD: From inception to completion, and I'm including the original version of it, I think it took a year and a half. I wrote the original version, and I got a grant through AFS for the original version and then I was like, this isn’t going to work, and then I changed this and worked on that for a little bit and then we shot in March 2022. So almost a year ago, that's just crazy! Editing took about six or seven months, I would say. In between all of this, I had moved to Atlanta for a little bit for like eight months and so I was in Atlanta, and then I flew back, we shot the film, flew back to Atlanta, started editing, and then while I was in the process of that, I had such a great time on set and I was like, I need to come back to Austin. So I moved back to Austin and I kind of hit this roadblock with the film. I'd done a couple of passes on it but it just wasn't feeling right and I was editing myself and it just felt off. So I reached out to Matt, who was our AD and the co-editor, and I was like, “Dude, can you just help me with this?” and we cut it together with his help and we finished the film in four days, just in my room working together on it. It was so great to have that other perspective and he added so much to it as a whole. Luckily, we weren't starting from scratch, but Matt just helped get it to that finishing line. He was the push that we needed.

HFC: Was that the first time you've had a co-editor? And how was it collaborating like that?

RD: It was great! It’s so funny, dude, I'm 37 now but I feel like me 10 years ago would have been so weird about it. Because you have this weird ownership over the stuff that you do and it's especially funny with film because film is so fucking collaborative. I think I’m at a really good place now as an artist or whatever, where I just feel a lot more confident. It was an amazing experience having him there because it was nice for him to see the story, and to get his added perspective on it. So yeah, he was great! Matt was fucking awesome and that was an amazing experience.

HFC: If there's one lesson you learned from making this particular film, what was it? I'm sure there's multiple lessons but is there one that you kind of keep going back to?

RD: Yeah, this is kind of a broad one, and this is a lesson I feel like works for any filmmaker: Just be okay with things changing. When the original actor pulled out, I just had so much anxiety. It was like this whole thing is gonna fail. Blah, blah, blah, but it ended up working out for the better! So, learning to be okay with that. Literally you can plan, plan, plan, plan, plan, and then something completely out of your control will happen and change your trajectory, but it helps to learn to just be okay with that. Having the confidence to be like, okay, take a breather, how the fuck are we going to fix this? What are we going to do? Like yeah, you might have this idea of what the film can be but then you have to also kind of go with it sometimes and be like, okay, let's just make sure we stick to our intentions with the story even though we're not shooting in a swamp in Louisiana or even though we're not doing these certain things this way or that way.

HFC: What got you started with filmmaking? Was it at a particular moment or film?

Akira

RD: Up until middle school, I wanted to actually write young adult horror. I was a big fan of R.L. Stein and Christopher Pike and I would always write little horror shorts. I was obsessed with Are You Afraid of the Dark and those kinds of books. That was my trajectory, that was the thing that I wanted to fucking do and there's a part of me in another life that feels like I went that way and maybe one day I'll do it because they’re still near and dear to my heart. But then my stepdad, funny enough, showed me two films, and I don't even think he realized they had an inspiration on me. One was Akira and the other was Big Trouble in Little China. It's like one of those things where you see something and you just have an epiphany, you know? I was just like, oh, this looks fucking fun! Like I want to do this! Then from there the whole obsession was born and I started out doing sketch comedy videos. By that point, I was really into film. I was an early adopter of Netflix, I worked at a theater in high school and all my money went to Netflix when you could still get the three DVDs, you know? And I just consumed so much shit before I went to film school. I would listen to commentaries; I watched any fucking special edition DVD. I would find out what inspired the people that I liked and went down deep rabbit holes. I feel like Pulp Fiction is the gateway film for a lot of us. There was a really great feature on the special edition DVD where, instead of closed captions, it listed every single film reference in Pulp Fiction. I wrote them all down and tried to watch as much as I could on Netflix. But yeah, in college we were doing sketch comedy and again, we just picked up a camera and did shit. This is the early days of YouTube and we’re submitting videos to YouTube and getting really good views and it was like, cool, this could be a thing! Then we stopped and a year later we came back to it and by the time we came back to it, YouTube was already oversaturated with Donald Glover's stuff, the Lonely Island boys, fucking Whitest Kids U Know, there was just so many sketch comedy groups, right? And I was like, and this isn't intended to sound braggadocious at all, but I feel like if we had stuck with it, something could have happened. I don't think we would have been like fucking Christopher Nolan filmmakers, but I think at the very least we could have been writing for Comedy Central shows or TV shows. I was really proud of the stuff we did back then. Maybe it's juvenile as fuck and it's so stupid but I thought my trajectory was going to be comedy. I was obsessed with BBC comedy shows and I thought I was just going to do sketch but then at a certain point, I think I just felt like I wanted to be taken a little more seriously as an artist and there were things I didn't think I could really say through sketch that I could say though short form stuff, so I started to do more of that. I did a couple of episodes of a TV show that I wrote and directed in college and then I ended up directing a thesis film in school and shot it on Super 16mm; it's a piece of shit. [Chuckles]. But we shot it on film and man, it’s so embarrassing to go back and watch it! There are moments of it that I'm really proud of but no one will ever see it.

But when I moved to Austin, I was trying to figure out, like, I'm sure you know this, you graduated school and you're like, “Fuck, no one has the time or we don't have the access to equipment, like what the fuck am I gonna do?” Thankfully, I had a DVX camera, and we shot a little bit more sketches and they looked a little bit better and I was proud of those new round of sketches but again, they didn't really go anywhere, so I was trying to figure out what the fuck to do. My friends are starting to work in the industry and I was like, I didn't want to just jump right in and work as a PA, that just never interested me and I feel like it stunted me connecting with people in ways. I think it's taken me a long time to connect with the filmmaking community here. It’s funny with Hyperreal, I was reading this book and it inspired me, so I started a repertory film series called Cinema 41 from 2010 to 2014. We were pretty active and, I think it was David, you guys did the Miracle Mile screening and we did Miracle Mile in 2010 and I'm friends with the director on fucking Facebook and I was like, I should have fucking reached out to him and told him, “Hey, they're showing your movie again!”

Miracle Mile

HFC: That’s so cool! Miracle Mile is one of my favorite movies!

RD: That movie bums me out so much! [Laughs].

HFC: It's one of those weird movies where it's so sad. It's a full on apocalyptic movie but there's so much dreamlike bizarreness in it that it’s got a different energy despite the nuclear apocalypse being the main thing.

RD: 100%. Have you ever seen Last Night?

HFC: I've heard of it! I'm a big fan of those “happens in one night” movies!

RD: Last Night is a really good post-apocalyptic film. But it's cool because it's supposed to be at night, but it never tells you how the world is going to end but everyone knows the world is ending at this time and it's supposed to be at night but it's still bright outside. The implication is the sun is exploding but it's this Canadian film and it's fucking dope, dude! If you get a chance to see it, it's really good. But yeah, we did a lot of screenings and stuff. Then from there, I got a job with the Austin Film Festival as the film department director in 2013 and that was okay. I mean, I learned a lot about how to navigate festivals, but it just wasn't the job for me. It was not what I thought it was going to be. So, I left that, kind of fucked around, did improv for a really long time, directed some shows that won some awards. I started to do a lot of stuff that was combining social justice with improv and the last big show we did was about prison reform but using improv as a tool for that and then right around 2018, no 2017, I started to get serious about doing another short. The first grant, I got through AFS and then we did a short and that played some festivals and then I got a second grant from AFS and we were going to do a feature but the pandemic just killed any motivation to do that [Chuckles] and then I wrote What They Found and then I got another grant through AFS to get it done while also using the other grant I had gotten, so there's been no straight line! Then pepper in acting gigs and stuff; I got to be in this movie on Amazon Prime. It's just this weird fucked up trajectory, right? Where there's been no clear path to any of it and, yeah, who knows? I don't know, I feel as I get older, I'm just like, maybe I should have kind of jumped right in after school, but then I also think about that and I couldn't afford it! I can't afford to get $75 bucks a day, and then not get paid on time. It just was not feasible for me to do that. So yeah, sometimes I wish I did but then I'm happy about the experiences I've gotten. I feel like it's all kind of fed into what I do now.

HFC: You mentioned you worked on a couple of shorts and you even had an idea set for a feature that you were planning to do. Do you still want to eventually try that out? Do you have an idea for a feature? Or do you still want to focus on shorts?

RD: Oh, I think I’m done with shorts for awhile, for sure. I think they're just too expensive. I do have a couple ideas for a short, though. I’ve been really into this, again, this is like film school shit, but Dogma ’95. I don't even think they realized it when they kind of made the manifesto, but there is something really inspiring about these guys. They were already established filmmakers when they decided to create this manifesto and there's something inspiring about being so wrapped up in the technology of at all and I think What They Found is great and I’m very proud of that experience with the last two shorts and I feel like there are a lot of conversations about the cameras and the lenses and the lighting, but to me, it was like, man, I know I'm supposed to care about this stuff but I kind of don't. [Laughs]. I just want to focus on the story and the acting, so part of me was like, well, what if we did strip that all away? What does that look like? You know, definitely there is a fine line, but I think I'm coming at it with more experience, so I feel good about it but I feel like it could easily fall into just sort of amateurish sort of category so it's making sure the story and the acting first and foremost are on point. I bought an early 2000 Sony Handycam where I was like, let's shoot something on this, and, boy, if we missed, we missed, but at least we fucking tried! So that's kind of where I'm at right now. But because I have never written anything I didn't do, I’m trying to write stuff that might require a bigger budget and being okay with not doing it and just writing a piece and not feeling burdened by budget or whatever. I'm learning to try get in that kind of mindset and work on longer pieces.

HFC: Is there a particular dream project of yours that you'd love to undertake?

Are You Afraid of the Dark?

RD: Going to back to what I was saying earlier, I would love to direct and be a part of a horror anthology series for kids like Goosebumps or Are You Afraid of the Dark? Man, I’m not kidding, those were so inspiring! Especially as I get older and realize how inspiring those shows were to me as a kid and shaping my imagination and how I approach doing creative stuff. It was fucking priceless, so I would love to do something there. I saw the Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark movie recently and I thought they did a really good job! It’s still for teens or whatever but it doesn’t feel dumbed down.

There’s one book especially that comes to mind that’s called Scared To Death. It’s this like young, forgotten young adult novel. It’s about a bunch of bratty rich kids who are dealing with a ghost of a nanny that they literally scared to death but parts of it get really dark and for whatever reason as a kid, I really loved that book. I couldn’t even tell you the author, I just remember the name and the cover. There’s a series of books I’m 100% convinced Stranger Things pulled from a little bit, it’s a series called Strange Matter. Nobody remembers this fucking series! I swear it’s not a Mandela Effect! It exists! I read it as a kid! But yeah, to do something like that, something that was forgotten. You know, Goosebumps is the big one but there was a bunch that I read as a kid that are just fucking gone! But yeah, that was a very long-winded way of saying, yes, I would love to do a horror anthology series for kids.

HFC: What’s a film coming out this year that you’re excited about?

RD: Oooh! That’s a really good one! [Laughs]. Damn, I was just thinking about this the other day. Why do I feel put on the spot? Oh okay yeah! I’m fucking stoked to see Creed 3! I love the Rocky series man, I love it!

HFC: So Creed 3 is your hyped movie for this year. What was your favorite piece of art from last year?

RD: The Banshees of Inisherin. Loved it! I saw it in Ireland, which was amazing. I would have loved that movie regardless because I love Martin McDonagh but yeah, that fucking movie was so good! It was probably my favorite thing last year.

HFC: Seeing movies in places other than where you live is something I need to do more because when I caught Decision to Leave at a theater in Brooklyn, it just added a whole new layer of enjoyment.

RD: I saw La La Land opening weekend in Los Angeles and–that movie gets a lot of shit–that movie resonated with me! It’s a really fucking good movie and I get the arguments on why people don’t like it, but I fucking loved it. My girlfriend and I were both surprised at how much we loved it after we saw it, and I’m sure seeing it in LA had something to do with it, but again, I would’ve loved that movie outside of LA. But yeah, Banshees of Inisherin is the first that comes to mind. I read a really cool play by Martin McDonagh, funny enough, called The Pillow Man, which is really fucked up and really dark. But plays are interesting because it’s kind of hard to read some plays because it’s like, this is meant to be seen, not read, but reading this play was really cool.

Hailing from Dallas, Texas, Justin Norris lives and breathes for one thing: movies. When not constantly telling people he’s “working” on a script, film review, or novel, he’s actually really trying to work on those things, guys, just trust him! Anyway, he’s also into casual reading, being an intense New York Jets fan, playing pickup basketball, and of course, catching a flick at the local theater.

To get more personal, follow the jabroni at:

Twitter: @DaRealZamboni

Instagram: justinnorris12

Letterboxd: DaRealZamboni

Medium: https://medium.com/@justinnorris12