Wes Anderson’s Netflix Shorts Show The Director Refuses to Stop Growing

Wes Anderson may be Hollywood's most recognizable auteur working today. If you took a still from any of his movies and presented it to a random person on the street, a shocking amount of people would probably be able to identify it as his work. This often leads to criticism that his films are all style, no substance—and memes attempting to parrot his style. But Wes Anderson’s new slate of four short films for Netflix shows the substance of his work goes much deeper than the symmetrical shots and pastel color palettes these trends attempt to ape. Not only is his style more than what any AI generalization could express, it's also constantly evolving and being further perfected.

This collaboration with Netflix comes in the form of four short films all adapted, impressively faithfully, from Roald Dahl’s short stories. Anderson, well known for having a collection of A-list actors who frequent his movies, pulls from his ranks to get Ralph Fiennes as Roald Dahl and Asteroid City and The French Dispatch bit player Rupert Friend as the star of the short The Swan. The rest of the cast: Benedict Cumberbatch, Ben Kingsley, Dev Patel, and Richard Ayoade, who all play multiple roles across the four shorts, are newcomers to Wes’ odd and wonderful worlds, but fit in perfectly. Ayoade especially feels like an actor who should have been starring in Anderson’s work for the past decade now and hopefully will be returning in the future.

Roald Dahl’s works are no stranger to film adaptation and have seen many retellings and reimaginings over the years, from members of the American film canon like Mel Stuart’s 1971 Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory, to cult classics like Danny DeVito’s 1996 Matilda. Even Anderson previously adapted Roald Dahl’s work in his delightful animated film The Fantastic Mr Fox. While many directors have found inspiration in Roald Dahl’s work, Wes Anderson seems perfectly, and possibly uniquely, positioned to bring the late author’s stories to life. Both Dahl and Anderson use similar conceits to achieve their goals in storytelling. Roald Dahl’s stories, while ostensibly for children, are often macabre and handle complex and adult themes. Dahl had a fascination with horror (don’t believe me? go read Lambs to the Slaughter) and used whimsical characters and fantastic settings in juxtaposition to the much darker themes he explored to make his stories suitable for children.

Similarly, Wes Anderson’s films at face value are known for their twee characters, eccentricity, and idiosyncratic comedy. But he fills his world with deeply lonely and sad characters, and the overarching themes of his oeuvre center around grief and reconciliation amongst dysfunctional dynamics. Both artists employ a lack of sentimentality in their works. Characters often speak in a deadpan tone or otherwise exhibit apathy or disproportionate emotions toward the situations they find themselves in. It seems obvious why Wes Anderson would be drawn to Roald Dahl’s works in the first place and why the adaptations work so well.

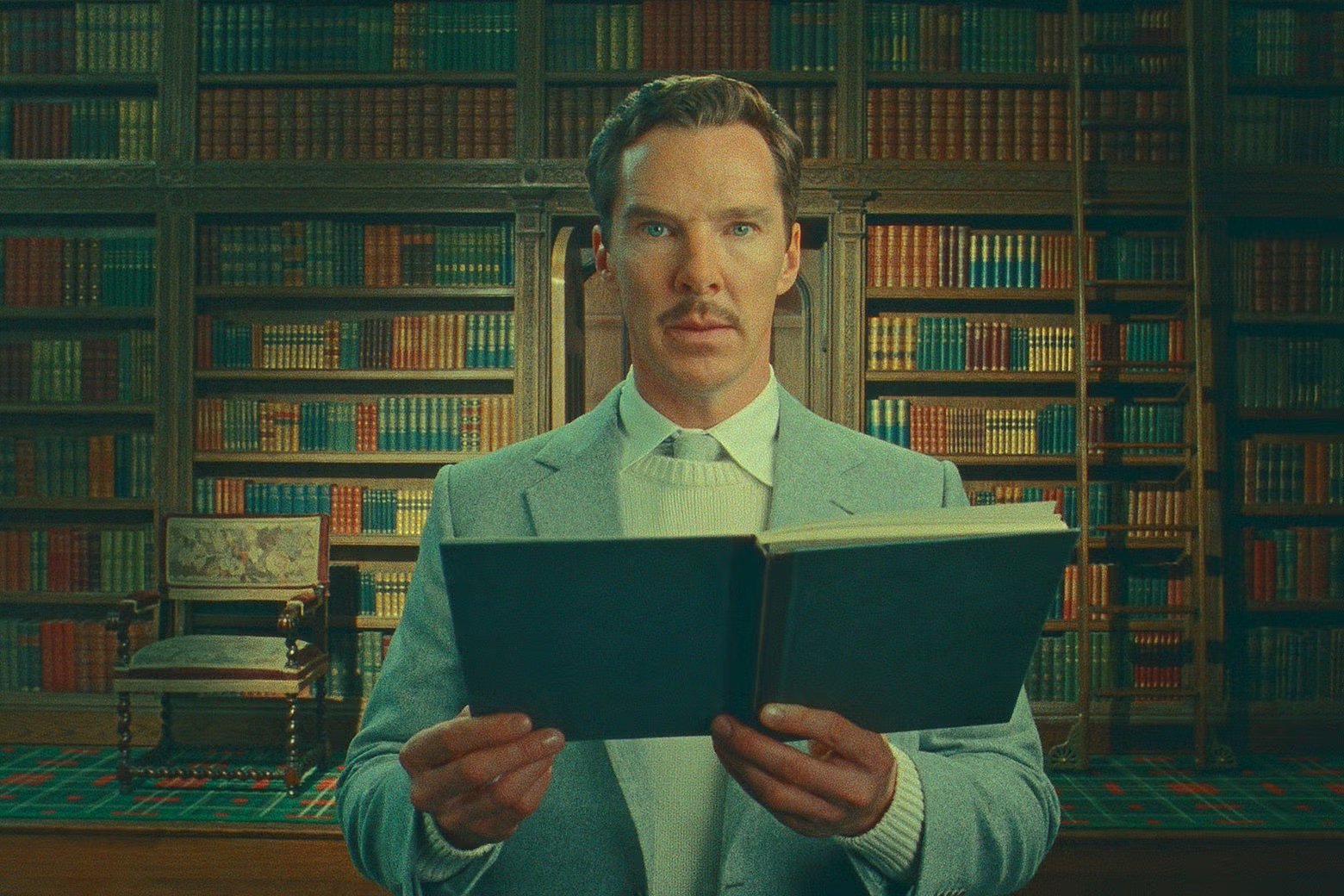

Anderson’s headlining short, The Wonderful Life of Henry Sugar, tells the tale of Henry Sugar (Benedict Cumberbatch), as he attempts to learn to see without his eyes after reading the account of a strange man (Ben Kingsley) who mastered this peculiar power. At 39 minutes, this is the longest of the shorts, allowing Anderson to flex his stylistic muscles the most. The other three shorts—The Swan, The Ratcatcher, and Poison—all clock in at an incredibly quick 17 minutes. These depict a man recounting the story of his childhood bullies; the unique methods of a local ratcatcher; and a man attempting to save himself from a deadly snake, respectively. Due to their incredibly short nature, recounting any more of their plots would spoil too much. The best way to experience the shorts would simply be to dive right in without further background.

In all of these shorts, Wes Anderson redefines what it means to adapt a novel for the silver screen. Each of the short stories’ characters exists in a space between the story and the viewer, breaking the fourth wall to actively narrate the short to the viewer as they watch. The style of book adaptation Anderson has created here acts more as a visual companion to the original stories rather than retellings. In each of the four short films, the dialogue matches the stories as originally written by Roald Dahl almost verbatim. By playing with the narrative style of the shorts in this way, Wes Anderson blurs the line between the oral tradition of storytelling and the old movie adage of “show don't tell.”

This adaptation style works far more than it doesn't—and may set a trend for other movie adaptations of books in the future—but it may also be the shorts’ greatest weakness. Anderson’s characters in other films often don’t show the level of emotion we expect them to, or express themselves in the ways an average person would—see: Luke Wilson in The Royal Tenenbaums, or much of Jason Schwartzman’s performance in Asteroid City—but this ends up amplifying the emotional impact when characters break this mold. Outside of the brilliant conclusion to The Ratcatcher, the auto-narrative style of the shorts’ dialogue and the fourth-wall-breaking delivery limit the actors from expressing humanistic emotion in a way that would make the emotional cruxes of these shorts connect in the way that so many of Anderson’s other works have.

Wes Anderson’s experimentation doesn’t stop with the real-time narration of the shorts. We watch as sets construct and deconstruct themselves between scenes, faux production assistants come on screen to retrieve props from our characters or, in one clever sequence in the main short, do Ben Kingsley’s hair and makeup in real time on screen while a Wes Anderson-signature miniature diorama is being executed above their heads.

The perfect distillation of everything Anderson attempts to achieve in this project happens in The Wonderful Life of Henry Sugar when Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sugar is behind the wheel of a car. Anderson chooses to back project the moving road background to simulate driving, a methodology that will be incredibly recognizable to fans of older films. On its own, using back projection to simulate driving looks artificial to a modern audience. But Anderson plays with viewer expectations of his work and his reputation for symmetry by centering Cumberbatch in frame, explicitly revealing the artifice of the shot by showing the projector screen and some of the set surrounding the obviously stationary car.

Anderson has always examined the artifice of film in his works. You only need to look as far as this summer’s enigmatic and beguiling Asteroid City for a prime example of this. But these shorts find the director at his most explicit and inventive in this regard. This is the work of a director at the same time hyper-aware of and completely shrugging off the criticisms levied at him. Anderson confronts the artifice in his work head on and only grows stronger for it.

Despite Wes Anderson’s universally recognizable style, from Bottle Rocket’s early beginnings, to the tremendous Grand Budapest Hotel, to now, he refuses to grow complacent in his style, ever expanding his bag of tricks. This collection of shorts feels like the culmination of ideas Anderson started playing with in both of his last two features, pulling elements of multi-leveled meta narratives from Asteroid City and the short story, mixed style elements of The French Dispatch. Each short lasts just long enough to leave the viewer wanting more. His latest works may not convert any of his detractors, but they present an exciting new way to handle textual adaptation in film that is certainly worth experiencing. As an admitted Wes Anderson fan myself, I can’t wait to see him apply his ever strengthening skills to his next feature film.

For anybody who would be seething if I didn’t rank the shorts, here you go:

The Swan

The Ratcatcher

The Wonderful Life of Henry Sugar

Poison

Disagree? Find me behind the Hyperreal merch table.

Colin Page is a full-time data scientist and even more full-time horror nerd living in Austin, TX. When not at his day job or watching movies, Colin can be found doing grad school homework, getting lost in the woods, attending DIY music events around Austin, and behind the merch table at many Hyperreal events. Stop by and tell him why his movie takes are bad. Find him on Letterboxd: https://boxd.it/2efct