The Debate of Good and Evil: An Interview with John Pielmeier

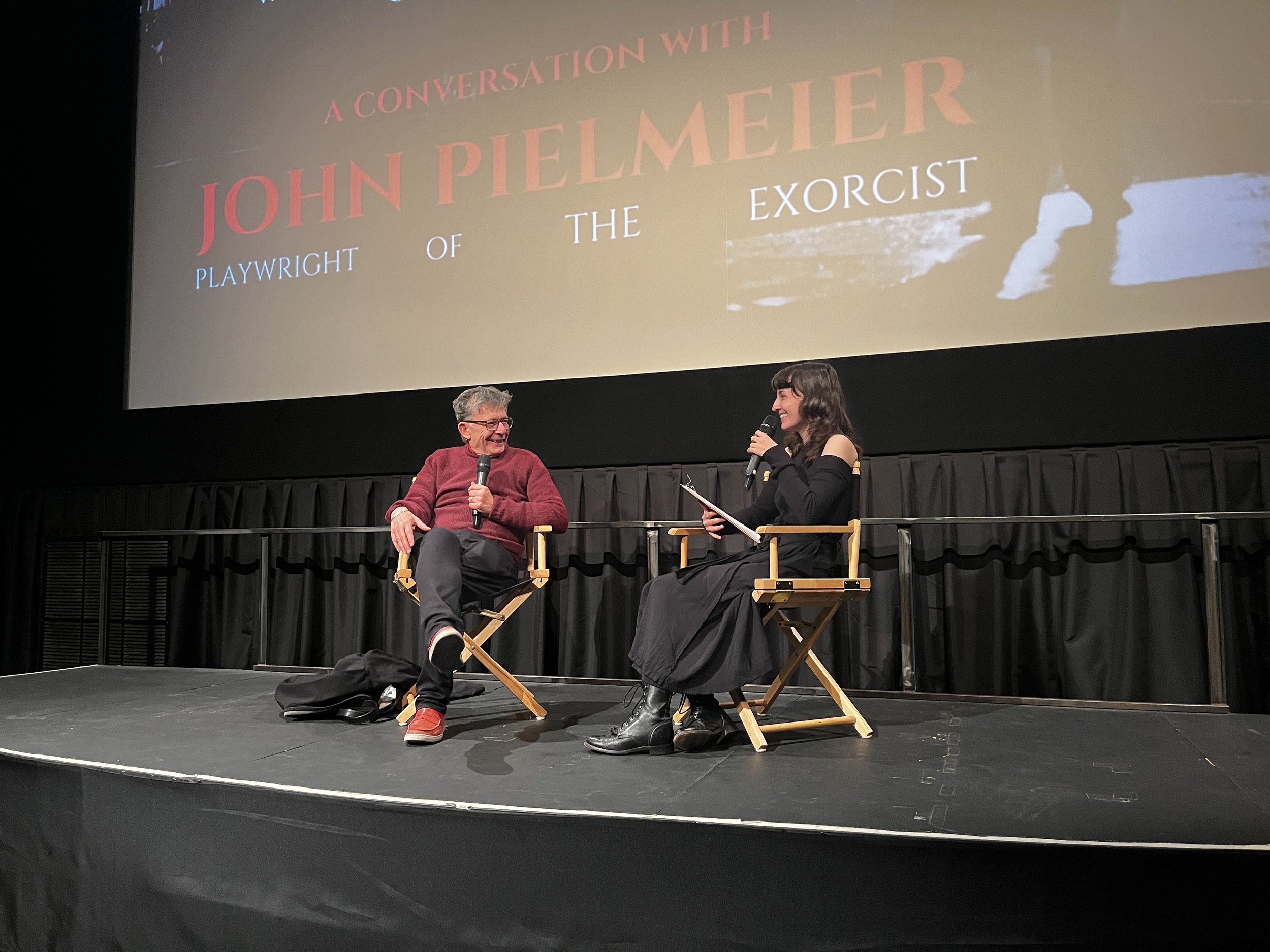

This interview was conducted as a post-screening Q&A on October 23, 2023, following a screening of The Exorcist (1973) part of a William Friedkin retrospective running at New York City’s IFC Center. John Pielmeier penned the stage adaptation of The Exorcist and (among his many writing and theatre credits) is perhaps best known for writing the play script and screenplay for Agnes of God.

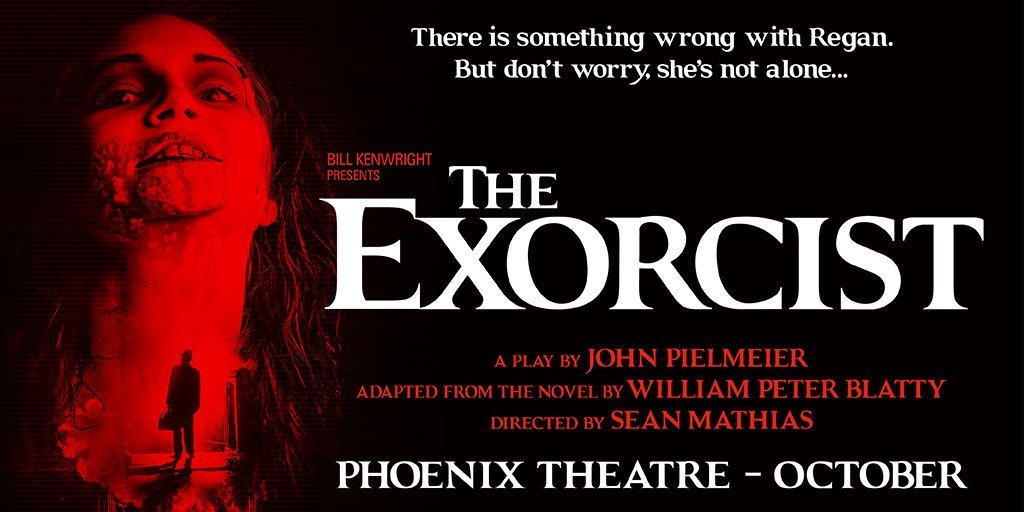

John Pielmeier’s The Exorcist played at Los Angeles’ Geffen Playhouse in 2012 starring Brooke Shields, and again in 2017 on the London West End at the Phoenix Theatre featuring Ian McKellan as the voice of the Devil.

When one watches the film, you quickly realize that it is not about Regan at all. We see her deterioration, but we do not stay with her. Friedkin often directed his camera to the reaction of Karras and the reaction of her mother Chris instead. We sit with their helplessness and hopelessness at what they are experiencing.

I often refer to this as my comfort film I watch when I am upset, and people usually laugh or think I'm trying to sound intentionally eccentric. The reality is we live in a world that is often very cruel, and this film gives me hope. It raises many questions concerning the existence of God, and the Devil, of good and evil; and really does not answer them. I know there is evil in the world. I do not know if there is a God, but The Exorcist always reassures me: in a world where God may not exist, perhaps goodness does. Perhaps all we have is each other, and perhaps that is enough.

Lucia: So, can we start with you walking us through how you became professionally attached to The Exorcist script?

John: Sure. A number of years ago, I got a call from my Los Angeles TV-Film agent who said there were a couple of producers who had acquired the stage rights to The Exorcist and they were looking for a writer. They wanted to talk to me about it.

So, I spoke to them. I said, “Yeah, I'm interested. Let me reread the book. I'd read it when it first came out. I’ll read it over the weekend, and we'll talk on Monday.”

I read it over the weekend and got very excited about it and came up with some ideas that I thought were very interesting and theatrical. I thought really, it lent itself—believe it or not—so incredibly to the theatre. And so they called me back on Monday, and I sort of gave them my pitch. And they said, “Great, we'll set up a meeting with you and Bill Blatty.”

Blatty lived on the East Coast, as do I. So that it was all set up. And about two days before the meeting happened, I got a call from one of these producers, and they said:

“The meeting’s off. We couldn't get the rights.”

And I said, “Well, I thought that you had the rights.”

And he said, “Well, we almost have them.” [audience laughter]

And then I said, “Okay.”

Then in the meantime, Blatty called me and said, “Come, I want to meet you anyway.”

So, I went down to Blatty’s home in Bethesda, Maryland and had a wonderful meeting with him. And he gave me the rights. Which was fantastic. So that's kind of how I got connected with this piece.

Lucia: Wow. That is very cool. So, the film is celebrating its 50th anniversary—

John: Yeah, I love the fact that this was the original film. This is not the director's cut. I didn't realize we weren't seeing that.

Lucia: Yes, shortly before he [Friedkin] died, he relinquished the Original Cut. For a long time, he only allowed the Director's Cut to be shown on screen. It's a 4K Restoration.

John: But this was not the Director's Cut.

Lucia: No, this is the Original Theatrical.

John: Yeah, the Original Theatrical. Yeah. And I hadn't seen the Original Theatrical since it first came out. So, I loved seeing this and comparing it to the Director's Cut. That was fun for me.

Lucia: Oh, I'm glad. So… 50th Anniversary. The book is a few years older than that. Why do you think the story is so evergreen? Why has it endured for so long?

John: Because I think it's really not—as you said earlier—it's not about a little girl being possessed. It's a movie about faith and belief and good and evil. And it's a movie that really sort of poses questions, [but] it doesn't provide any necessary answers. And there's lots of interesting complications and contradictions in this movie and questions that simply go unanswered. And I think that is incredibly intriguing to people.

And obviously, it made a huge splash when it first came out because it broke so many rules about horror movies back in 1973, when it first appeared. Now, we're sort of used to a lot of these things, though, these rules that it broke. I think it is the fact that it's still a compelling movie, is incredibly well written, incredibly well done, performed, and directed. I think that's why it still works so beautifully.

Lucia: So, in addition to The Exorcist, you have written a wonderful play called Agnes of God, as well as the screenplay for the film which starred Jane Fonda, Meg Tilly, and Anne Bancroft. If you are not familiar with Agnes of God, it is a about a psychiatrist investigating a nun who strangled her newborn and claims that it was conceived through Immaculate Conception. So, it seems like you have written before about science versus miracles, and crises of faith.

John: Yeah, exactly. This was sort of right up my alley.

Lucia: So, what is drawing you to these stories?

John: You know, I asked that myself. I don't really know. You know, I write a lot about the abuse of young people.

I'm not sure why I'm drawn to that. I've written about it in other media also, in some other plays. So, I'm fascinated by the kind of controversy… Well, I love innocence and evil sort of combined in the same package. You sort of see that in Regan. There's an element of that, although it's not evil, but there's an innocence and a lack of innocence, and in my character of Agnes in Agnes of God and some other things like this—I did an adaptation for television of Sybil. Again, I'm fascinated by all the different people who are in each of us.

Lucia: It’s almost a debate between the good and evil.

John: Pardon me?

Lucia: It’s almost a debate.

John: Yeah, yeah, I guess, but I don't know what the answer is. I don't know who wins, you know.

Lucia: I guess it's up to us to decide for ourselves.

John: It is, I mean, obviously, in this movie, the Devil theoretically loses. But that's because you had to have some kind of ending to this that would be satisfying to us all. But if you believe in the Devil or evil, it's still going on, if you believe in it.

Lucia: I was curious, do you think the shadow cast by the film in the book skewed audience expectations? Or did it kind of work to your favor in that they were already frightened when they came into the theatre to see your play?

A production still from the Geffen Playhouse performance in 2012.

John: Well, yeah, in the original production at the Geffen in Los Angeles, it was a very bare bones play directed by John Doyle. I had written a very spare script, and he made it even sparer, and more… sort of symbolic and really pared it down. Some people absolutely loved it, and some people hated it, and it wasn't very scary.

We sort of all felt afterwards, well, the audience is coming because they really want—on some level—to be scared. So, I basically threw out that script and totally rewrote it for what became the London/UK production, in a much scarier, creepier way.

Lucia: How would you say they changed?

John: In my first production, the focus of the play was really on Merrin. In a way, he was the central focus of the play.

In the new version, Regan is really the focus of the play, although, as you said, before, it's really not at all about Regan. This is happening because of all the people around Regan.

I mean, the movie kind of emphasizes Karris’ vulnerability, but I did the adaptation from the novel. And the novel has some very interesting things that are not present in the movie script concerning other characters that I sort of drew on and expanded on.

Chris, for example, had a child before Regan, who died possibly because of Chris's—or so Chris believes—own carelessness. And so, there's that hanging over Chris, as she goes through this whole experience with her second child, and the fear that this daughter might die in a way not unlike her first child died. [That] is sort of her vulnerability.

Merrin, in the book, it's very clear that the Devil wants to have… is calling Merrin to him, that the Devil has lost prior contests with Merrin in the book. Merrin has had several exorcisms with the Devil in other countries. And Merrin has always won. And each time, of course, Merrin physically has gotten weaker and weaker, and the Devil doesn't want to lose. He wants to win Merrin.

So, Merrin’s vulnerability is obviously his physical self, and maybe other secrets that he's carrying that the Devil knows. We don't really find out what those are, but the Devil is very much calling Merrin back for this, essentially, final confrontation.

I also play up the character of Burke Dennings. Burke is only in literally two scenes in the movie, and he's a fairly important character in the play that I wrote and much more so in the book. The book mentions that Burke was at one time a seminarian. He left the seminary to become a movie director. And obviously, he has a problem with alcohol. And, so Burke, who dies about halfway through my play, has vulnerabilities himself.

So, it's really a story for me about people's weaknesses. And the Devil, metaphorically or literally, is preying on these weaknesses. He’s using Regan as a way to get to these other people. Doesn't matter about Regan. I mean, in the Catholic theology, if Regan were to die, she'd go straight to heaven. She's only a child. It's not her fault. She's not committing any sins or anything like that. She goes straight to heaven. But it's the other people, the adults, that the Devil wants. And is thrilled, of course, in the end to get a priest.

He says at one point, “I want a priest to burn in my fire.” He's after Merrin, and when he doesn't get Merrin because Merrin dies, then he's thrilled to have the opportunity to get Karras.

Lucia: So, I want to go from themes to the design of the play. Something I noticed in the film is the importance of staircases, to the emotional states [of characters]. Burke and Karras die on the staircase, they're always running up and down to her [Regan’s] room. His [Karras’s] mother descends the stairs in the dream… So, how do you…

Lucia and John: How do you do that in the theatre?

John: I mean, there was one set. There was a staircase in London, but one of the tricky things in the theatre is that's really not going to completely work. So, I don't know… the play will be coming to New York sometime in the near future. I'm not sure what the designers are going to do with that.

It is obviously very important that the bedroom becomes the center of the piece. I mean, what's wonderful about this piece as a play, is that essentially the house is the main set. And, I sort of think…. they did this in London, and I thought it was very effective that you never really got a sense… You never really saw the whole house. You just got pieces of it here and there. So, I don't know how that's going to be handled in New York. We'll see. I'm not a designer. I leave that up to the people who know what they're doing.

Lucia: Of course. So, people who have not seen The Exorcist in recent memory often refer to the special effects as what they remember. Can you tell us any specifics in regard to how the effects were accomplished on stage? I think Teller of Penn and Teller fame…?

John: Teller did the show at the Geffen, [and] a wonderful magician by the name of Ben Hart did it in UK. We actually did have a head spin that was so incredibly effective in London, and I can't tell you how it was done. I mean, I know how it was done, but I'm not allowed to tell you how it was done. [audience laughter]

What I found interesting about seeing the movie on a big screen again, is that when you see it on a TV with high-definition, the head-spin is just ludicrous. But it didn't seem as ludicrous to me watching it tonight as it is when you see it on a TV screen. Nowadays, of course, it would be done much better. But, I think the effects on the big screen were very effective tonight.

Lucia: Yeah. Yeah. And the thing about the head-spin, too, that I think doesn't really register is it cuts from her starting to spin to Karras’ reaction, and then back to the end of it. So, you almost wonder, you know, he's been doing this exorcism for hours. He has had no sleep. Is this something he is hallucinating? Because you don't see it [go] all the way around.

John: Yeah.

Lucia: So, tension never really breaks into film. There is rhythm throughout with the use of sound: these long periods of silence and distance and then BAM, you know, the candle, the drawer—

John: I was very aware of the use of sound tonight in the film, particularly with this fabulous sound system which I don't quite have in my living room. So, I love that fact. What’s interesting to me also about the movie is a lot of people don't realize that there are no real jump-scares in this movie.

There's the flash of the candle, which goes up the attic, which is a bit of a jump-scare. And there's a very loud phone ring about two-thirds of the way through the movie that can be a kind of jump-scare. But not what we're used to in horror movies today. Pretty basically nothing.

Lucia: Was there any kind of similar audio design for the stage? Or did you guys take a different approach?

John: It's a totally different approach. And that will change with the production in New York from the production in London.

Lucia: You keep mentioning the production in New York. Is it coming soon?

John: I can’t talk about… hopefully. We have a wonderful director and a wonderful producer attached.

Lucia: Oh, great. Congratulations.

So, Regan's existence becomes very medicalized. I saw many people cringing at the arteriogram. I saw someone shake their head when the doctor said, “Can we run the test again?”

John: That's so incredibly intense. I remember that's the scene that affected me the most when I first saw the movie back in ‘74.

Lucia: Is there anything similar on the stage?

John: To a certain degree we can't really do those, you know, the arterial thing. But, there are certain things that happen in the various examinations that she goes through. I don't want to spoil.

Lucia: Oh, that's fine. That's fine. Can you talk about the choice to have an adult actress play Regan?

John: Yeah. We've decided we really have to have an adult play Regan, just because in the climate nowadays, it just would be too upsetting and too risky to have an actual 12-year-old masturbating on stage with a crucifix. Can't do that. So, in every production, we've found some wonderful actresses over the age of eighteen, who are totally, convincingly twelve.

Lucia: Interesting. So, you’ve said in the past you have wanted the Devil to have a presence on stage. Are you able to talk about that?

A production still from the Geffen Playhouse performance in 2012.

John: Well, yeah. The Devil certainly has in the play a lot more dialogue than he does in the movie. They are scenes that the Devil has between him and Karras. As Karras is doing his exploration of whether or not this is a real “exorcizable” phenomenon.

I mean, Karras comes in saying: “I'm a psychologist, this is just a sick child. I don't believe in the Devil. I just think this is a weird psychological something going on.” And finally, he's convinced. The Devil basically has to convince him, because the Devil wants an exorcism. Because he wants Merrin.

The Devil says, “Give me an exorcism, I want an exorcism!” And so, the Devil in a way has to convince Karras that this is real enough for Karras to go to the bishop to get permission to have an exorcism approved.

Lucia: Back to the writing process. I'm curious, you mentioned Bill Blatty was speaking to you when you were first signed on. Did he have any influence? Or were you given free rein?

John: He was incredibly generous with me. I mean, I met with him several times. And he basically was very, very generous. Bill was mostly concerned about the fact that… Bill was a very, very devout Catholic, which I am not, and he was very concerned that I keep that feel in the play. You know, he didn't want me to travel into any areas of priest abuse and things like that. That obviously is very much in people's minds for the last 20 years with the Catholic Church.

So, he didn't want any of that and I felt I had to respect that. So, I ran everything by him many times and he approved—occasionally he'd make little suggestions. There’s a—it's wonderful for me to hear—there's a moment in the movie that actually got a laugh tonight. One of the psychiatrists is talking to Regan, the Devil, and asks a question. And the Devil's answer is just sort of [growls like Mercedes McCambridge] and everybody sort of reacted.

And that's Bill Blatty. I mean, that was Blatty. Who would, sort of, reenact that scene for me sometimes. Oh, he just loved that sort of groan and grunt. So there's a lot of Blatty in this that I enjoy seeing.

Lucia: I think we can open up to questions if anyone… Yes, you?

Audience Member: So, it said that Blatty and Friedkin disagree about having a definitive answer. Like, why this is happening to Regan. Right? And that's why the Director's Cut was released, I was wondering your opinion…?

John: Yeah, Friedkin put… There's a scene in the movie where Merrin and Karras are resting after the first big exorcism scene. They're sitting on a staircase. And there's a scene that was added in where Merrin talks about why Regan.

Which is sort of about what I said, it's not about really not about Regan, it's about everyone else in this house. Which doesn't really give an answer: Why specifically Regan as opposed to any other 12-year-old girl or boy in the world… why is never really answered. No, not much more than what I just said. I mean, I might explore that more. I'm actually interested… I've been thinking about that more. But there was an essay in the Times recently, I don't know many of you may have read it, in which the writer prefers this cut to the Director's Cut, because he said the Director's Cut tries to explain too many things. And this doesn't explain, which makes it more interesting. I'm not sure which side I come down on. But I do feel that people today want to know more about: why Regan? That's sort of a natural question.

The Exorcist, 1973

Lucia: Anyone else?

John: How many of you… I have a question for all of you. Is anyone here seeing this for the first time? [A few hands raise.] Oh, very interesting. So go see the find the Director's Cut and compare it in your heads to this. And what you think about it.

Lucia: We will be playing the director's cut on 35 mm on Thursday at 6:45.

John: Oh, really? Oh, cool.

Lucia: We're playing both.

John: Okay.

Lucia: In the back?

[A question is asked on the challenge of frightening people on stage.]

John: It’s a challenge to do it on stage. And that's one of the exciting things about it. You know, how do you… it's so much easier to do a jump-scare, for example, in a movie, because it's all about cutting and lighting than it is on stage. So, you have to figure out how that's going to happen. If that's what you want, or even just building suspense. Yeah, so that's exciting because of the challenge of doing that.

Audience Member: So having not seen your adaptation but having read Agnes of God, which was one of my one of my favorite plays as a teenager…. I was wondering if you think of those two have a relationship with each other?

John: Oh, Agnes, compared to The Exorcist? Oh, absolutely. You know, on some level, they're kind of dealing with the same thing. Obviously, I'm obsessed with Catholicism. I'm not a Catholic now, but I was raised a Catholic, but I'm obsessed with stuff that my religious experience… how it resonated in me. What worked and what doesn't work. What I miss of it, and what I don't miss of it. I don't know if that answers your question. I've written other pieces along those lines. Not all my plays deal with Catholicism and religion by any means, but I'm fascinated by the spiritual elements of our lives.

What does that mean to any of us? What is spiritual? You know? How do we deal with that part of ourselves that we might call spiritual. Most people, I imagine, in this audience don't deal with any organized religion in any kind of way. Some may. But we all have to tackle those questions. I think we all tackle them in in different ways and find different answers—if we find any answers at all.

I mean, what fascinates me and what I love about The Exorcist, and what Agnes of God for me is all about, is asking questions and not expecting any answers. I don't like answers, but I love questions.

Audience Member: Is it easy to become possessed?

John: Is it easy to be possessed? I don't know how to answer that. No, I don't know... Well, what do you mean by possessed?

I mean, if you're talking about possessed in terms of some other being or demon or whatever, coming into you, I don't know what I believe about that. I certainly think it's very, very rare.

But, you know, at the same time we can be possessed by ideas, by passions; we can be possessed by love. Falling in love is a kind of possession, so perhaps it is easy on that level. Depends on how you define possession.

Audience member: How do you define it?

John: I've never thought about that. I don't think it's possible for me to be possessed by a demon.

I have been possessed by love. I've been possessed by ideas. I've been possessed by stories and plays. You know, a number of years ago I was actually on a vacation and suddenly had a realization about a fictional character that someone else had written, that I had never thought about.

I became so possessed by the thoughts that came about because of this vacation in connection with this character that as soon as I got home, I wrote a novel in five weeks about this character. That, to me, was possession. And I don't know how I wrote it in five weeks, but I did. That's possession. When you do something that is not possible for people to do.

Audience Member: So how are you dealing with mysticism in terms of writing for the stage? Because in the film, you're able to get an image of the statue in the beginning, right? A single image you're able to repeat.

John: You can do that in stage. You can do flashes of images.

I mean, where we are with projections in the theatre right now is just amazing. So yeah, there are flashes of the Devil, which is called Pazuzu… a real demon from—I don’t know if it's Iranian or Iraqi mysticism…

Lucia: I think it might be Mesopotamian.

John: Pardon me?

Lucia: It might be Mesopotamian.

John: Mesopotamia. Yeah. I've seen little statues of Pazuzu. It's a funny name. But you can do that. You can show images of that. It's, you know, it's hard to talk about what the future New York production will be, because it's a little different from what we did in London. I don't know what's going to turn out. A lot of that is special effects and design and so forth, which is not my strong suit by any means. So, I can't really answer that yet. In a year or two, you can ask me that question again. And it’ll be answered better. I hope.

Lucia: I think that is all the time we have. Thank you so much for coming. It was a pleasure to have you.

John: Thank you. And look at the Director’s Cut. God. I wish I could come back and get your thoughts about that. Thank you so much. This is just great.

Lucia: It was wonderful to have you.

The only thing Lucia likes more than privacy on the internet is peeking out from beneath her rock to write about films—particularly the many parables, talismans, and delights we receive from horror, science fiction, and fantasy.