The Blair Witch Project: A War of the Worlds Hoax for the Internet Age.

In October of 1994, three student filmmakers disappeared into the woods near Berkittsville, Maryland while shooting a documentary… A year later their footage was found. Or, that’s what was said.

Living in the age of misinformation, it’s almost nostalgic to look back on the 90s and a time before algorithms told us what to believe. Local newspapers were thriving, the evening news was a trusted source, the world wide web was not quite ten years old, and “word of mouth” happened by talking to your neighbors face to face, not via hashtags. But that was changing. By 1999, advancements in technology were rapidly changing the landscape of communication and entertainment for the average consumer. An entire generation is marked by this shift in the paradigm to a world defined by personal technology. As the world was changing and the rule-book was yet unwritten, filmmakers and college buddies, Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez had an idea to take advantage of this shifting landscape and access to technology to create a film that bent the parameters of entertainment. And they wanted to do it on the cheap. So, they wrote a 35 page script, cast three actors, set up camp in Seneca Creek State Park, Maryland, and the legend of The Blair Witch was born.

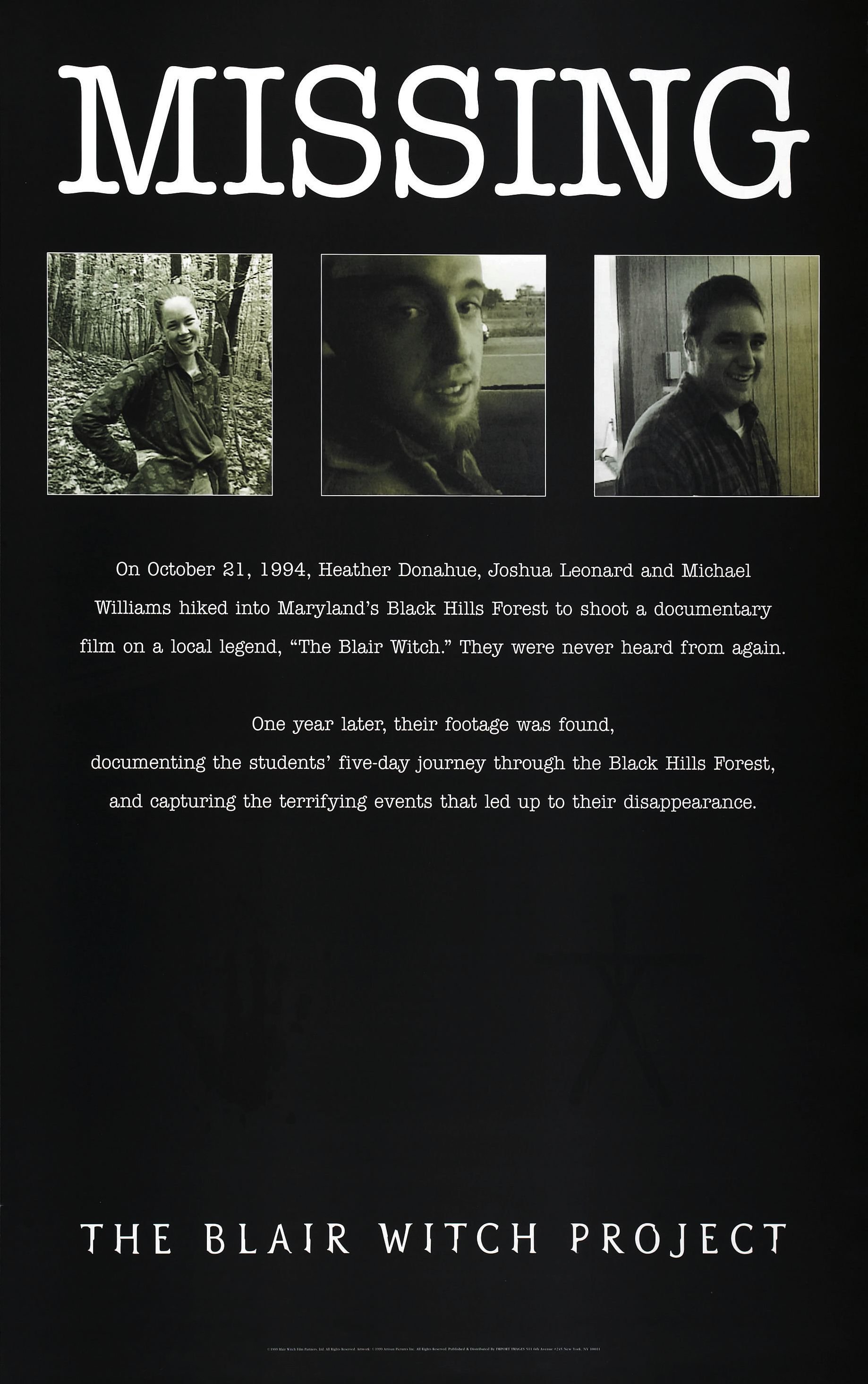

A film poster for The Blair Witch Project circa 1999

For those unfamiliar, The Blair Witch Project is a found-footage style mockumentary in which three young filmmakers set out on a mission to investigate the legend of the Blair Witch that has haunted the woods around Burkittsville, Maryland since the 18th century, and are never seen again. I wouldn’t say it’s a particularly scary movie; It’s not a slasher film like most 90’s horror fare and never reaches a real climactic confrontation with a big bad, knife wielding villain in a ski mask. It’s a tight 80 minutes of three people being starved, taunted, and sleep deprived by a witch on a big screen with the conceit that, hey, this really did happen. And whether or not you, the viewer, believe a centuries old witch is behind it is, at this point, secondary to the mythos that is The Blair Witch Project.

Filming took over a week and the actors, Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams, and Joshua Leonard, have since reported that it was an extraordinarily grueling process where they lived the film 24/7. They couldn’t shower, had little food, and only found mental respite from the process when the fear and panic got too intense and their safeword, “Taco,” had to be used. A word choice they all came to resent, by the way, as it did little more than remind them all of how hungry they were. Accessible and affordable Hi8 camcorders were used by the actors who were their own film crew. Messages from the directors to move the story along were tucked in 35mm film canisters hidden in milk crates, and scattered along their hiking route to be located using GPS. In total, The Blair Witch Project cost under $500,000 to make and few involved thought much would come of it. But Myrick and Sánchez had a plan. They set up a website.

The film’s iconic, ambiguous ending almost didn’t exist. After shooting wrapped, producers had the cast and crew return to shoot a few bloodier endings, but none stuck and the original ending is the one we continue to enjoy 20 years later.

It’s thought that the Blair Witch Project was the first film to primarily market through the internet and, perhaps by extension, go viral. But it wasn’t the film itself that garnered buzz. At Sundance, the marketing strategy was to ask festival goers for tips to help find the missing actors. The website hosted staged press conferences with actors posing as Maryland police urging the public to stay safe and on guard. This strategy was so successful that a real police officer in the Maryland area called the filmmakers and offered his assistance to locate the missing “filmmakers.” Afterall, the actors used their real names in the film for authenticity, a choice Heather Donahue came to regret as it made finding employment as an actor after the fact extremely difficult.

But people were nuts for it. A real found footage documentary where the subjects are missing is a thrilling prospect. You may believe it, you may not, but it doesn’t matter. The thrill of watching a horror film where you can’t comfort yourself with reassurances that, “it isn’t real, it isn’t real, the Blair Witch isn’t coming for me because she isn’t real” was, and still is, too good to pass up. Even today, knowing without a doubt the Blair Witch is a work of fiction, it’s fun to watch and put yourselves in headspace of the unwittingly deceived because no one could ever get away with this today, right? But The Blair Witch Project was not the first piece of media to take advantage of new technology and rumor to create a piece of fiction that transcends entertainment.

In addition to targeting younger audiences through the internet, The Blair Witch Project trailers were shown before Episode I of the Star Wars Prequel Trilogy, the Phantom Menace.

Sixty years before, 23 year old Orson Welles had an idea similar to that of Myrick and Sánchez. Commercial public radio broadcasting was not yet 20 years olds, but Welles had already been working in radio entertainment for a few years. By October 30, 1938, Welles’ Mercury Theatre troupe was well into their residency performing radio plays live on the air. That night, however, Welles decided to bring to his team an updated adaptation of H.G. Wells’ iconic science fiction story, War of the Worlds, where the actors would perform the story as radio broadcasters live reporting an alien invasion as it unfolds. Despite opening the broadcast with a disclaimer that the story to follow was a production of Mercury Theatre on the Air, it’s reported most listeners didn’t tune in until the broadcast was well underway. Therefore when the broadcast reported alien ships landing at various sites across the country, listeners in the vicinity, for lack of a better phrase, freaked the fuck out. Allegedly, families evacuated en masse. Police departments, hospitals, and fire departments were inundated with panic-stricken calls. An investigation was made into the broadcast to see if any laws were broken, but in the golden-age of radio, the innovation employed by Welles was truly novel and it was determined no standing laws were broken.

In the decades since, it’s been proven the scale of hysteria caused by the infamous broadcast was perhaps not quite as widespread or intense as was reported at the time. For Orson Welles, however, the impact of his broadcast was perhaps more fruitful than he could have hoped. He was shortly thereafter approached to create what many believe to be the greatest film ever made, Citizen Kane, and cemented himself as one of the greatest multi-hyphenates of the 20th century.

A Penfold Theatre Co. June 2022 production that dramatizes the events of Orson Welles’ now infamous broadcast.

I personally find it hard to believe Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez weren’t well aware of the success Welles found in this exploitation of new technology and its unlearned users. So, by the time The Blair Witch Project debuted at Sundance in 1999, the heavy lifting had already been done. Their website was used by believers as a primary source against skeptics. The actors were instructed to stay under the radar to keep up the illusion that they were missing and presumed deceased, just as their IMDB profiles stated. In the decades since its premiere, the legacy of the Blair Witch lives on. There have been several sequels and a video game. An annual Blair Witch camping trip takes place each October. But the true legacy of the Blair Witch holds a lesson we would all be remiss not to take heed of; be careful what you believe to be true, especially if you read it on the internet. Also, Taco is a terrible safeword.

Katy is an Austin-based writer and theater maker from the Rio Grande Valley (PURO 956). Besides binging trash TV and listening to political podcasts, she enjoys talking to strangers, running with scissors, and spending time with her three-legged cat, Scout. Follow her on Twitter @MatyKatz.